Joshua Abraham Norton, b. 4 February 1818

The following illustrated remarks were presented by Emperor's Bridge Campaign* founder and president John Lumea at The Emperor's 197th Birthday, the Campaign's "party and presentation of recent findings" held on 3 February 2015 at the Eric Quezada Center for Culture and Politics in San Francisco.

IT SEEMS THAT, for the vast majority of people who know anything about Emperor Norton’s dates, the answer to the question of his birth year begins — and basically ends — right here.

Headstone at Emperor Norton's grave in Woodlawn Memorial Park, Colma, Calif. Photo: John Lumea (taken on Emperor Norton Day (8 January) 2015).

This is the stone that presides over the Emperor’s grave just down the road in Colma — Woodlawn Memorial Park — and that was placed there in 1934, when the Emperor’s remains were moved there from the Masonic Cemetery in San Francisco, where they had rested since his death and original burial in 1880.

The stone was commissioned and paid for by the Emperor Norton Memorial Association, whom we’ll meet again shortly.

The dates carved into the granite couldn’t be more plain: Born 1819. Died 1880.

:: :: ::

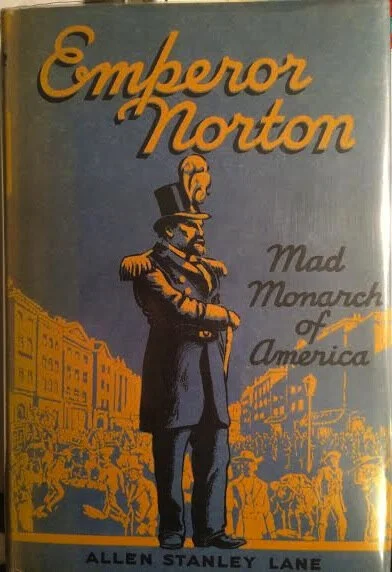

JUST FIVE YEARS LATER, in 1939, Allen Stanley Lane wrote and published Emperor Norton: The Mad Monarch of America, the book that would become the standard Norton biography for the next 50 years — and Lane was just as plain as the gravestone that Joshua Norton was born in 1818.

Lane wrote:

“He was not always an Emperor. That day in 1849 when he first came to San Francisco, a young fellow of 30 or so, he was a mere civilian like everyone else. Just plain Joshua Norton, with no fancy title whatsoever.

Nor were his parents of royal blood. They were English Jews of the working class, his father being a farmer and trader. John Norton and his wife, Sarah, were among the 4,000 British colonists who went out from England in 1820to settle at the Cape of Good Hope. With then they took their two small sons, Joshua Abraham, born in London in 1818, and Louis, born in 1816.”

In 1986, William Drury wrote and published Norton I: Emperor of the United States. This book became the new biographical standard and likely will remain so — although, hopefully, we won’t have to wait another 20 years until the next one.

This much, Drury and Lane agree on: Joshua Norton was born in 1818. Drury is skeptical of finding a specific date for Joshua’s birth date — but, unlike Lane, he does give us a clue why we should think that 1818 is the year.

Drury writes:

“Joshua Norton was born in the London borough of Deptford on a day lost to mortal memory. No trace of a birthdate can be found in England’s incomplete files, but there is one broad hint in the archives of a land far from England. On May 2, 1820, when John and Sarah Norton arrived at the Cape of Good Hope with three small children, one a babe in Sarah’s arms, John told an immigration clerk that the boy they called Joshua Abraham — that one there, clutching his mother’s skirts and gaping fearfully at the Hottentots who handled their baggage — was two years old. So there you have it from a father’s lips; he was born in 1818.”

:: :: ::

SOME OF THE MODERN-DAY genealogists who have done the best and most thorough work on the Norton family tree — and on Joshua’s branch of the tree — are themselves the Emperor’s family members.

We’ve been very lucky to have two of these as conversation partners: Julie Driver, in Ontario, is the Emperor’s great great great great niece. And Hazel Dakers, in London, is Joshua’s cousin through Marcus Norden — the brother of Joshua’s mother, Sarah Norden.

A footnote about Hazel: Just as there are chartered accountants in the U.K., there are chartered librarians. Hazel is the latter; she been a respected librarian in the UK, including at the British Library, for many years. She now is retired but works professionally as a genealogist, with a particular interest in the diaspora and ancestry of British Jews — including Joshua and his family — who emigrated to South Africa in 1820. Hazel has been working on this for 20 years, so it’s very good to have her in the loop.

Julie makes the point that, in South Africa, it pretty much just is accepted — amongst the Norton family; amongst genealogists; and amongst others who know his story — that Joshua was born in 1818. Not 1819.

The primary reason for this seems to be that Joshua’s immigration story is better known there than it is here.

Joshua’s family emigrated to South Africa in early 1820, as part of a colonization scheme in which — over a period of about 18 months — some 25 ships sailed from England to South Africa.

The vast majority of these ships landed in 1820. Those passengers who remained in South Africa became known as "the 1820 Settlers."

The standard reference for information about the ships and settlers that defined this emigration is The Settler Handbook, written and published by M.D. Nash in 1986 — the same year that William Drury wrote and published his biography of the Emperor. Indeed, Nash draws heavily on the same "Cape Archives" — the public archives from the Cape of Good Hope — that Drury relied on to make his argument that Joshua was 2 years old in 1820.

Nash confirms that Joshua's family — Joshua; his father and mother, John and Sarah; and his older 3-year-old brother, Louis — sailed as part of Thomas Willson's Party on the ship La Belle Alliance.

Initially boarding at Joshua's hometown of Deptford, on the River Thames, in late December 1819, the ship was delayed for more than a month due to ice on the river. When the ice finally cleared, the Belle Alliance made its way upriver to its port of departure at the Downs (near Deal), where it departed on 12 February 1820. The ship arrived in Table Bay, near Cape Town, on 2 May 1820.

The passenger list that William Drury alludes to in writing that, "[o]n May 2, 1820, when John and Sarah Norton arrived at the Cape of Good Hope...John told an immigration clerk that the boy they called Joshua Abraham...was two years old" — this was one of a number of passenger lists, documenting both "ends" of the journey, that would have been produced for the voyage of the Belle Alliance.

A couple of important things to know:

A fifth member of the young Norton family — Joshua's brother, Philip — was born en voyage. So, any South Africa passenger list would have included five Nortons. Any "London list" would have included only four.

Julie Driver notes than an early London list did not include the Nortons, as they had yet to join the Willson Party — and that any London list including both the Nortons and additional details such as the ages of the passengers likely would have been a list created closer to the time of the ship's final departure on 12 February 1820.

Such a London list, from the Cape Archives — a list that (a) includes the Nortons; that (b) does not include their newborn, Philip; and that (c) does list passenger ages — is included in Nash's Settler Handbook and also is reproduced at 1820Settlers.com, a respected online hub of the history and genealogy of the Settlers movement.

The list — very possibly from early February 1820 — shows Joshua as being 2 years old.

A sidebar: The site 1820Settlers.com had listed Joshua as being born in February 1819. But, in early December — in response to the Campaign's findings — the site updated Joshua's birth date to 4 February 1818.

You can read about this here.

:: :: ::

WITH ALL OF THIS testimony — from both of Emperor Norton’s major biographers of the last 75 years; from the genealogists and Norton family members who have done the most thorough work on the Norton family tree; and from the earliest immigration records — pointing to a birth year of 1818 for Joshua…

Why does 1819 continue to stick — and why is 1819 on the gravestone that was placed in 1934?

All signs seem to point to a biographical essay on Emperor Norton written in 1923 by Robert Ernest Cowan.

Robert Ernest Cowan in 1930. Source: "California Bibiographers: Father and Son," Robert G. Cowan interviewed by Joel Gardner (Regents of the University of California, 1979).

Robert Cowan, born in Toronto in 1862, arrived in San Francisco with his family in 1870. He attended Berkeley for two years, from 1882 to 1884. He was a bookseller in San Francisco for 25 years, from 1895 to 1920.

During this time, he carved out a reputation as a book collector and a bibliographer. And in 1919, Cowan was hired by the Los Angeles-based copper mining heir, William Andrews Clark, Jr. — himself a book collector, with particular interests in English literature, Oscar Wilde and fine printing — to be Clark’s librarian and advisor on book purchases, a position that Cowan held until shortly before Clark’s death in 1934.

Not long after Cowan began his association with Clark, he became the inaugural editor of the new California Historical Society Quarterly. He was the editor of the Quarterly when he published, in the October 1923 issue, a brief essay on Emperor Norton in which he stated flatly and without explanation that the Emperor was "born February 4, 1819."

William Drury offers a theory as to why Cowan may not have needed an explanation.

Drury is tweaking Cowan here for apparently backing as authentic a proclamation that now — largely because of Drury — is widely regarded as a fake: the one published by the Oakland Daily News in August 1869, in which the paper — poking fun at San Francisco — had Emperor Norton calling for a ridiculous “bridge to nowhere” running from Oakland to Goat Island to Sausalito to the Farallons.

Drury writes:

“How they must have laughed in Oakland when that proclamation appeared in the News, for the bridge it proposed would have been an astonishing structure, meandering aimlessly all over the place from Oakland Point to Goat Island before wandering off to Sausalito in Marin County and then heading west for thirty miles beyond the Golden Gate to the Farallone Islands (a clump of rocks in the Pacific inhabited only by seals and seabirds, with one lonely lighthouse-keeper for company).

San Francisco’s newspapers, hearing the titters that came floating across the bay, completely ignored the joke out of civic pride, refusing to reply to it and thereby acknowledge its existence. Today we might never have heard of it if a collector of Norton memorabilia, one Albert Dressler, had not found it in Oakland’s archives and included it in a little book he published himself in 1927 under the truncated title Emperor Norton of United States.

Dressler, who printed a facsimile of the original newspaper paragraph, was the first to suggest that the decree was genuine, saying: “San Francisco Bay was ordered bridged by Emperor Norton in 1869; the following Proclamation appearing in the Oakland Daily News, August 19, 1869.”

This claim caught the eye of an eminent historian, Robert Ernest Cowan, chief librarian and bibliographer of the Arthur Andrews Clark Library at the University of California in Los Angeles, who seemed to dismiss any quibble concerning the document’s authenticity by saying, in a slim volume of limited edition published solely for collectors of Californian curiosa: “Whether or not it was drafted by the Emperor is insignificant, but its contents are extraordinary and of the greatest prophetic importance.”

The entire tone of the paragraph in which Cowan made that comment, however, left the distinct impression that he did consider the manifesto to be authentic. In fact, he concluded with the surprising statement that, because Leland Stanford was “attempting to secure Yerba Buena, to make it a great terminal depot” for his Central Pacific, “the vision of the gentle old Emperor was not so fantastic after all,” quite forgetting that any bridge that went traipsing off to a barren outcrop in the Pacific would have been truly fantastic and of no possible use to San Francisco or anywhere else.

Cowan’s willingness to accept the proclamation as the Emperor’s handiwork gave it instant credibility, for “Sir Robert” — as he was known among bibliophiles — was not only a respected archivist but could even claim a passing acquaintance with His Majesty. He was eight years old in 1870 when he and his parents met the royal ragamuffin on the station platform in Oakland, where they had just disembarked from a train that had carried them from Canada. The Emperor, he fondly recalled in a conversation with his publisher, Ward Ritchie, had patted his head and told him to be a good boy (after which, we may suppose, he turned to the lad’s father, ink bottle in hand, to sell him a bond).”

So, Cowan’s claim about Emperor Norton’s birth date may have been accepted and embraced for no other reason than that Robert Ernest Cowan said so.

It also is worth noting that, when the Emperor Norton Memorial Association formed in January 1934, for the purposes of organizing a burial service for the Emperor’s interment at Woodlawn cemetery — and raising funds for a proper headstone to be placed at the grave — Cowan, who died in 1942, was still alive.

Program for 1934 service of dedication for Emperor Norton's new resting place and gravestone at Woodlawn Memorial Park, Colma, Calif. Source: Jewish Museum of the American West.

Remember that Cowan published his essay on Emperor Norton in the Quarterly of the California Historical Society. When the Memorial Association was doing its work in 1934, the president of the Association, Ernest Wiltsee, was Vice President of the California Historical Society.

So, Cowan and the officers of the Memorial Association were people who almost certainly knew one another and who were part of the same world. Indeed, Cowan probably was the person of greatest stature in that world who also had written about the Emperor. So, it stands to reason that, when deciding which birth year to include in the epitaph for the stone, the Memorial Association’s primary appeal was to Cowan’s essay.

:: :: ::

BUT WHERE DID Cowan’s very specifc date — 4 February 1819 — come from?

This is where things start to get especially interesting.

Joseph Amster is on the Board of The Emperor’s Bridge Campaign. Joseph is better known to many of you from his historical walking tour, where he portrays Emperor Norton.

Joseph spends a fair bit of time scouring the Emperor Norton ephemera collections of the San Francisco Public Library and the Bancroft Library, at Berkeley. This past December, whilst on one his regular rounds to the Library, Joseph stumbled across this item, which appeared on the front page of the Daily Alta California newspaper on 4 February 1865.

From "City Items" feature on the front page of the Daily Alta California, Saturday 4 February 1865. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Here’s what the Alta item says:

“HIS MAJESTY’S BIRTHDAY.—His Imperial Majesty Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Mexico, commences his forty-eighth year Saturday, February 4th, 1865. Owing to the unsettled questions between His Majesty Maximilian I, El Duque de Gwino, the Tycoon, the King of the Mosquitos, the King of the Cannibal Islands et al., the usual display of bunting by the foreign shipping and public buildings will be omitted on this occasion.”

"Commences his forty-eighth year" would mean that Emperor Norton was turning 47 in 1865 and thus that his birth date was 4 February 1818.

Certainly, a February 1818 birth date lines up with Joshua’s father's report, for the passenger list of the Belle Alliance, that Joshua was 2 years old when the family set sail in February 1820.

A birth date of 4 February 1819 doesn’t line up with that information at all.

It turns out that the Alta item actually makes a cameo appearance in Robert Ernest Cowan’s 1923 essay. Although Cowan presents the item to illustrate a different point, it’s clear that he is using the item to bolster his own claim about the Emperor’s birth date.

This is a photograph of the Alta item as it originally appeared in the California Historical Society's publication of Cowan's essay, showing how Cowan introduced and presented the item.

From Robert E. Cowan, "Norton I: Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico," in California Historical Society Quarterly, vol. II, no. 3, October 1923. (Digital copy at JSTOR.)

Here, again, is the original text of the Alta item, as it appeared in the paper on 4 February 1865:

“HIS MAJESTY’S BIRTHDAY.—His Imperial Majesty Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Mexico, commences his forty-eighth year Saturday, February 4th, 1865. Owing to the unsettled questions between His Majesty Maximilian I, El Duque de Gwino, the Tycoon, the King of the Mosquitos, the King of the Cannibal Islands et al., the usual display of bunting by the foreign shipping and public buildings will be omitted on this occasion.”

And here's Robert Ernest Cowan's 1923 edit of the Alta item:

“Owing to the unsettled questions between His Majesty Maximilian I, El Duque de Gwino, the Tycoon, the King of the Mosquitos, the King of the Cannibal Islands &c., the usual display of bunting on foreign shipping and on public buildings, in commemoration of our 46th birthday, will be omitted.

Feb. 4, 1865.”

Notice what Cowan does here:

He redacts the entire first portion of the original item — including the pivotal phrase "commences his forty-eighth year."

He presents the truncated remainder of the item as though it were a stand-alone Proclamation from the Emperor himself.

He inserts the fabricated phrase "in commemoration of our 46th birthday" — which was not part of the original item.

Pretty shocking.

The text that Cowan does use, plus the fact that Cowan "adds back" the date "Feb. 4, 1865" to the end of the "quote" — the date is part of the redacted portion — leaves little doubt that the Alta item is the source of his contrivance.

Indeed, the upshot is that Cowan acknowledges that Emperor Norton was born on 4 February.

But, by manipulating the original Alta item to make it appear that 1865 was the occasion of the Emperor's 46th birthday — rather than his 47th, as the Alta item indicated — Cowan is able to "retrofit" a source for his own claim of 1819, rather than 1818, as the Emperor's birth year.

As if to hammer home the point, Cowan references the number 46 twice in the same sentence, writing "forty-sixth birthday" in the introductory clause and inserting "46th birthday" into the quote itself.

:: :: ::

WHAT ARE WE TO MAKE of this? Why was Robert Ernest Cowan so invested in 1819 as Emperor Norton's birth year? Had Cowan staked some previous claim to 1819 — whether in a publication or a speech or a conversation? And had he done so with such certainty — and to such a prestigious audience (whether in public or private) — that now, in October 1923, it made sense for him to doctor a 60-year-old newspaper item in order to prop up his earlier story — even if it meant risking his own professional reputation?

Whatever is the case, it now appears that Cowan's claim of 1819 as the Emperor's birth year was the result not of human error — whether his own or someone else's — but, rather, of a conscious effort to conceal and to mislead.

For his own part, William Drury agreed that the Alta item was a hoax.

Here’s what he wrote:

“Nobody knew the Emperor’s age or the date of his birth. February 4 was significant for quite another reason. It was the fourth anniversary of the signing of a declaration of independence in 1861 by the first seven cotton states to secede: Mississippi, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas. Every year, on February 4, Southerners in San Francisco hung out rebel flags to celebrate the birthday of the Confederated States of America. The Alta, a staunch Union paper, was simply thumbing its nose at that display of Southern pride by pretending that the flags were flown to celebrate the birthday of a lunatic.

Such leg-pulling was commonly practiced by both sides. Southerners often tried to plant propaganda, thinly disguised, in Fred MacCrellish’s paper. He once received a seemingly innocuous scrap of verse, seventeen lines in length, and might have published it exactly as it was written had he not noticed that the initial letter in every line, reading from top to bottom, spelled out “HURRAH FOR THE SOUTH.” Before putting it in the Alta he made a couple of minor adjustments, changing only the first words in the thirteenth and fifteenth lines so that the acrostic now read: “HURRAH FOR THE NORTH.”

Then he scribbled under it, “Sorry, Johnny Reb.”

The Maximilian referred to in the Emperor’s “birthday announcement” was the Austrian archduke recently installed as Emperor of Mexico by Napoleon Ill. “El Duque de Gwino” was a sneering reference to William McKendree Gwin, a former United States senator for California and the chief political foe of David Broderick. Gwin, a Mississippian, briefly imprisoned by the North for his loyalty to the South, was now in Mexico, where, it was falsely rumored, Maximilian had made him a duke.

That February 4, it so happened, was the Confederacy’s last birthday. On April 9, at Appomattox, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his sword to General Ulysses S. Grant, and the war was over. And then, just one week later, in a theater in Washington, John Wilkes Booth fired his Derringer and Lincoln belonged to the ages.”

Drury asks us to treat the Civil War-era political associations with 4 February and the Alta's taste for pranks as grounds for throwing out the entire Alta item as a "hoax” (Drury's word).

It’s a little surprising that Drury is so quick to discount the item, given that it points to a birth date that supports his own stated conviction that Joshua was 2 years old, when the Belle Alliance sailed in February 1820.

Surely, it is possible that the Emperor's birthday and the Rebels' "Independence Day" really did happen to fall on the same day, providing the pro-Union Alta with a convenient synchronicity that was just too good to pass up.

Perhaps the first sentence of the Alta item is a factual statement and only in the second part is the Alta "taking the Mickey" out of the Rebels.

:: :: ::

WE CLOSE WITH A NOTE about Joshua’s circumcision.

Hazel Dakers points out that, since the advent of what she calls “civil registration” — public birth certificates — in the United Kingdom was not until 1837, some 20 years after Joshua's birth, the real “holy grail” of primary sources for Joshua’s birth date is likely to a be a synagogue record — which probably means a circumcision record.

Our friend, Judi Leff, is on staff at Congregation Emanu-El here in San Francisco. She has been spearheading an effort to place a plaque for the Emperor in the Jewish “Home of Peace” cemetery in Colma. Just this afternoon, the date for the plaquing ceremony was set for Sunday 3 May. That’s a Save the Date — so mark it down!

In connection with this effort, Judi has taken a great interest in finding Joshua’s circumcision record, so as to be able to establish — within a day or so — his likely date of birth.

According to Jewish tradition, newborn boys are to be circumcised as close as possible to eight days following their birth.

Those who are authorized to perform ritual circumcisions are known as mohels; and, at the time and place that Joshua most likely was circumcised — England, 1818 — mohels often were itinerant, and they kept their own registers.

Remember that Joshua was born in Deptford, which now is part of London but which, at the time, was in the adjacent county of Kent.

Judi has found a record of a circumcision of a Jewish boy by the mohel Myer Solomon, performed in Deptford on 13 February 1818 — which, one can't help but notice, is around eight days after 4 February 1818.

In fact, if Joshua was born after sunset on the 4th, then the 13th would have been considered the eighth day after his birth.

Solomon’s circumcision register was transcribed by Rabbi Dr. Bernard Susser (1930–1997) and placed online in 2003. This digital record of Susser’s transcription — which is what Judy found — is available here.

The relevant entry reads:

712 On Friday the eve of the holy Sabbath 7 Adar I '578 I c[ircumcised] Judah b Moses {Deptford; 13 February 1818}

In circumcision records, the name of the circumcised boy is presented as a Hebrew name for the son, followed by a Hebrew name for the father — in this case, "Judah b[en] Moses."

It was most common for an English Jew to be given an English name that reflected the Hebrew name. But this was not a universal practice — and many Jewish boys born in England were given English names that did not reflect the Hebrew name recorded in the circumcision register.

Although Hazel Dakers has been able to verify that “Moses” is a Hebrew name for the English name, John, of Joshua’s father, we’ve not yet been able to determine whether “Judah” is a Hebrew name for the English name Joshua.

This will be one of the next frontiers of our research.

:: :: ::

THE EMPEROR’S BRIDGE CAMPAIGN promoted this evening's event as an "annotated birthday party." We've come to the end of the annotations.

We still lack the ironclad proof of a verified synagogue record of Joshua Norton's birth or circumcision.

However, it does seem that there is more than enough evidence — circumstantial and otherwise — to "put to bed" the conventional wisdom of an 1819 birth date and to focus our attention on a window between, say, November 1817 and February 1818.

Indeed, I hope we’ve been able to give you plenty of food for thought this evening — at least enough to inspire you to raise a glass to the Emperor tomorrow on what most likely is the 197th anniversary of his birth on the 4th of February, 1818.

* In December 2019, The Emperor's Bridge Campaign adopted a new name: The Emperor Norton Trust.

:: :: ::

For more on our Emperor's Birth Date Research Project, please visit the project page here.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...