Did Joshua Norton Really Leave San Francisco Between Declaring Himself Bankrupt in 1856 and Emperor in 1859?

This is the third in our occasional series of Open Questions articles. These articles take "deep dives" into some of the most oft-repeated — but under-analyzed — historical claims about Joshua Norton / Emperor Norton. They offer source material for future exploration of questions that generally are presented as settled — but aren't.

ON 25 AUGUST 1856, the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin newspaper published the following brief notice:

Joshua Norton filed a petition for the benefit of the Insolvency Law. Liabilities, $55,811; assets stated at $15,000, uncertain in value.

Over the next few days, this news would find its way into other papers — for example, the final item in the "San Francisco Letter" that appeared in the Sacramento Daily Union on 1 September 1856.

The historical trail that bears witness to Joshua Norton's pursuits and habitats over the next three years goes increasingly cold and dark, until he comes roaring back onto the pages of the Bulletin declaring himself Norton I on 17 September 1859.

Increasingly cold and dark — but not entirely so. In fact, in November and December 1856 — just a couple of months after his bankruptcy filing — Joshua took out business ads in the Daily Alta California newspaper, showing that he was trying to carry on with some smaller-scale merchanting.

The listed address, the Tehama House, is where Joshua was living at the time. While not the first-class digs to which he'd ascended by 1852, this actually was a respectable hotel.

Here's the Alta ad from 9 December 1856:

Business ad for Joshua Norton. Daily Alta California, 9 December 1856. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

:: :: ::

CITY DIRECTORIES can be another way to establish a person's residency or business dealings in a given place. But, during this period of San Francisco's history, when the very idea and, indeed, the procedural regimen of an annual directory still was in development — and when high-quality personal information could be hard to come by — a person's absence from a directory did not necessarily confirm the opposite, i.e., that the person was not living or working in the City.

There were "false negatives."

The first San Francisco directory that survives down to us is Charles Kimball's book, published on 1 September 1850. Between 1850 and 1858, there are three years for which we don't have directories — and each of the directories for the remaining six years was compiled and published by a different person or firm. Things in Directoryland were very much in flux.

The year, 1856, that Joshua Norton declared bankruptcy found a business address listing for him — "Pioneer Hall, Wash'n above Kearny" — in that year's directory by Samuel Colville.

No directory survives for 1857.

But 1858 saw the publication of the first San Francisco directory by Henry Langley, a name that would be synonymous with the City's directories for nearly another four decades.

Langley's 1858 directory found Joshua Norton living in a down-at-heel boarding house run by a Mrs. Carswell at 255 Kearny Street.

Snippet of the Langley's 1858 directory for San Francisco with listing for Joshua Norton living at a boarding house at 255 Kearny Street. Source: Internet Archive.

Based on the Kearny numbering legend included in the directory, 255 was on the west side of Kearny between Broadway (south) and Vallejo (north). The Emperor's Bridge Campaign's* interactive Emperor Norton Map of the World features a pin that shows exactly where this boarding house was. (Click the pin to open a description in the sidebar). It's the steep area lined on both sides of Kearny by what is named the Peter Macchiarini Steps.

[Note: Peter Macchiarini (1909–2001) was the sculptor and, as it happens, longtime champion of Emperor Norton whose 1936 maquette of the Emperor — one of two that he created during this period — is the basis for the 2010 sculpture of Emperor Norton, created by Macchiarini's son and granddaughter Daniel Macchiarini and Emma Macchiarini, that presides over the main bar at the Comstock Saloon in San Francisco.]

One question that may be more relevant than it seems at first: In exactly which month was the San Francisco directory for a given year published during this period?

Langley's 1859 directory appears to be the first of his directories for which he provided this information in the book itself. The 1859 title page identifies the book as "The San Francisco Directory For the Year Commencing June, 1859." In other words, it was published in June 1859.

It stands to reason that the 1858 directory followed the same timeline.

What's important for our purposes is that a San Francisco directory published in June 1858 probably was being compiled, edited and typeset in the first half of the year.

This would suggest that Joshua Norton was living at 255 Kearny at least through the spring of 1858 — which, if true, would close the gap between his August 1856 bankruptcy and his September 1859 imperial self-declaration by nearly two years.

And it would go a long way towards resolving any supposed mystery about Joshua's whereabouts up until 15 months or so before declaring himself Emperor.

:: :: ::

It appears that the Langley's for 1859 was the first directory since Joshua Norton's arrival in San Francisco in late 1849 that did not include at least one or the other of a residential or a business listing for him.

Various writers and commentators have taken this as a sign that Joshua must have left the City for a time — some even going so far as to assert that he left for a few years.

This makes for a good story — "Once-Wealthy Businessman Loses Everything; Leaves Town; Returns in a Blaze of Glory." But there doesn't appear to be any evidence to substantiate it.

Indeed, in his original Proclamation of 17 September 1859, Joshua Norton describes himself as having been "now for the last 9 years and 10 months past of San Francisco, California" — perhaps the clearest testimony we have of his uninterrupted residence in the city.

It's worth noting that neither of Norton's major biographers — not Allen Stanley Lane in 1939 and not William Drury in 1886 — mention any possibility of his having left San Francisco at some point in the late 1850s.

Even Robert Ernest Cowan — a writer one might have expected to "go there" — doesn't. The historico-folkloric essay on Emperor Norton that Cowan wrote for the California Historical Society in 1923 has been enormously (and unduly) influential in shaping the modern Norton Myth. Though not wholly bad, the essay is riddled with undocumented historical claims that readily have been proven false — not least, because of Cowan's shameless penchant for plagiarism or just "making shit up."

But, on the question of exactly where it was that Joshua Norton worked out his "recovery" and reinvention, Cowan is uncharacteristically restrained, writing only that Joshua "retired into obscurity, and when he emerged in 1857, he gave palpable and distinct evidence of an overthrown mind." (That last line, Cowan cribbed from paragraph 5 of the Daily Alta's obituary of Emperor Norton, published on 9 January 1880.)

:: :: ::

THERE MAY BE a simpler explanation for Joshua Norton's absence from the 1859 city directory than that he exiled himself from San Francisco.

In his "Prefatory" to his 1858 directory for San Francisco, Henry Langley included a passage that amounted to a disclaimer against the expectation that the directory was — or could be — completely reliable.

The passage remained so relevant a year later that Langley quoted it verbatim in his Prefatory to the 1859 directory, noting [emphases added] that

any defects which may exist...[the compiler] has a right to expect, when the peculiarities of the undertaking are taken into consideration. There is, probably, no literary enterprise which is surrounded with so many obstacles to its successful prosecution, as the preparation of a work like the present; and especially in this city, where there is so much reluctance expressed by many persons to communicate the necessary information. In this respect, the compiler has met with so many cases where parties have refused their names, occupation and residence, that it has required considerable time and labor to complete the work in a satisfactory manner. He anticipates, however, that these difficulties will not exist to any considerable extent hereafter, and that a more universal desire will be exhibited to assist him in his efforts to establish, permanently, a work of so much importance to the city, as a complete and reliable Directory.

In its obit of the Emperor, the Daily Alta recorded, of pre-imperial Joshua, that "[a]fter his misfortune, he became determinedly morose...."

If, as many believe, we should interpret "determinedly morose" to mean "clinically depressed," it would not be surprising to learn that — especially after his declaration of bankruptcy in August 1856 — Joshua became increasingly withdrawn and reclusive, i.e., that he was beset with moods and adopted behaviors that are consistent with severe depression.

Perhaps Joshua was in an especially "bad place" in late 1858 or early 1859, when Langley was collecting information for the upcoming 1859 directory — so he withheld his details as a self-protective maneuver to help ensure that only his closest friends and former associates would be likely to visit him.

:: :: ::

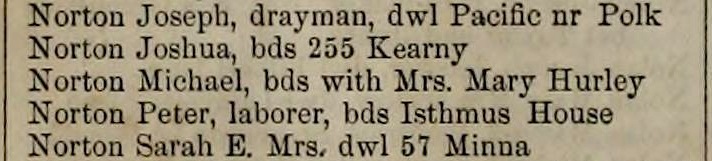

ALSO WORTH considering is this 1859 directory listing for a resident of 255 Kearny — the same boarding house, remember, where the 1858 directory listed Joshua as living:

Snippet of the Langley's 1859 directory for San Francisco with listing for a Jesse Norton living at the same address where Joshua Norton was listed in the previous year's directory. Source: Internet Archive.

"Norton Jesse, mcht." This "Jesse" doesn't appear in the available directories before or after 1859.

Did one of Henry Langley's staffers mistranscribe "Joshua" as "Jesse"? For the U.S. censuses of this period, the proprietor of a given boarding or lodging house provided the information about all of the residents of the house; residents did not provide the information themselves. If directory publishers like Langley employed a similar practice — delivering forms to boarding house proprietors rather than to individual residents — it's not difficult to see how poor penmanship could have led to a listing of "Jesse" for Joshua.

Might "Jesse" even have been the name Joshua provided to throw San Francisco off his scent and secure some additional privacy for himself?

Was Joshua Norton still living at 255 Kearny in early 1859 and beyond?

William Drury thought so.

In his 1986 biography of Norton — still regarded as the reference standard and used as the baseline for new research on Emperor Norton — Drury cues up his postulation by taking note of five of the Proclamations that the Evening Bulletin published in the four months after it published the Emperor's original declaration in September 1859. Drury writes:

[Bulletin editor] George Fitch knew by now that he had stumbled onto a good thing; the "royal proclamations were immensely popular and his paper's circulation had increased. he hoped they would continue and that Norton I — whoever he was — woud give them to no other editor.

But then came the day, 5 February 1860, that Norton had appointed for "the representatives of all parties interested" to gather at the Assembly Hall at Post and Kearny — the originally appointed venue, Musical Hall, had burned a few weeks earlier — to sort out the constitutional basis for the Empire.

Nobody showed.

As if to strengthen the case that Norton was vulnerable to slipping into a reclusive depression, Drury observes [emphasis added]:

There can be little doubt that Norton was deeply hurt. For five months, the Bulletin heard nothing from him....In May the pony brought word from Chicago that Abraham Lincoln had been nominated as the Republican Party's choice for President. That news infuriated the South, which seethed anew with threats to secede if "the gorilla" who had vowed to free the slaves should win the election. The hubbub in San Francisco's papers brought Norton out of his lodgings at last, determined to try once more to bring the nation to its senses. He called upon Fitch with another proclamation.

The Proclamation — calling for the dissolution of the republic — was dated 26 July 1860.

Note how Drury pivots immediately after delivering this information:

Norton no longer lived at 255 Kearny; either he was evicted for his bizarre behavior or had departed voluntarily, unable to endure the jeers and jibes at Mrs. Carswell's table when the Bulletin was passed around. His home now was a shabby hotel on Bush Street, the Metropolitan, whose proprietors apparently cared little about a tenant's idiosyncrasies so long as the rent was paid.

:: :: ::

IN LIGHT OF the rest of this discussion, the two main takeaways from the timeline that Drury offers here would appear to be:

1) Norton lived at 255 Kearny from early 1858 (at the latest) until early 1860 — the period before and immediately after he became Emperor.

2) The Emperor moved from 255 Kearny to the Metropolitan Hotel in early 1860.

William Drury's biography, wonderful as it is, doesn't include reference notes — which can make it difficult to check sources that he doesn't mention in the text itself.

For example, Drury claims that Emperor Norton was living at the Metropolitan Hotel by July 1860. But he offers no accounting for the fact that there is no listing for the Emperor at the Metropolitan (or anywhere else) in the Langley's 1860 directory — published in July 1860, as it happens — and that the first listing for Joshua Norton at the Metropolitan appears in the directory for 1861.

Perhaps Emperor Norton moved to the Metropolitan in spring 1860, and — given the publication date of July 1860 for that year's directory — his listing simply fell through the cracks.

Of course, if one were to allow that Joshua might have purposed to keep his name out of the 1859 directory, one could hardly disallow that explanation for his absence from the 1860 book.

Obviously, the storyline of Joshua Norton's whereabouts from his declaration of bankruptcy to his declaration is not without its gaps.

But the available evidence points to a narrative in which, most likely, the eventual Emperor remained a resident of San Francisco from his arrival until his death — his momentary "disappearance" from the city directories explained by clerical error; by the infelicitous timing of his change of address relative to the deadline for providing information for the 1860 directory; and/or by a moment of depressive reclusiveness in which Joshua Norton found himself for much of 1859 and 1860.

It would seem ironic, indeed, if such a moment — such an essentially anti-social personal crisis — was the backdrop for Emperor Norton's bold, eloquent announcement of himself and his claims.

There may be an explanation for that, too.

But it will have to wait for another day.

* In December 2019, The Emperor's Bridge Campaign adopted a new name: The Emperor Norton Trust.

:: :: ::

UPDATE — 8 March 2022

On 5 July 1859, Joshua Norton took out a paid ad in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin. The ad was a brief “Manifesto” addressed to the “Citizens of the Union.” It outlined in the broadest terms the national crisis as he saw it and suggested the imperative for action to address this crisis at the most basic level.

This was a little more than two months before Joshua issued his Proclamation — published in the same paper — declaring himself Emperor of the United States on 17 September 1859.

Together with what we already knew — that Joshua Norton continued to run business ads for nearly a year after his insolvency of August 1856; that the San Francisco directories of 1858 and possibly 1859 included listings for him...

The Manifesto is one of three additional pieces of evidence that Joshua Norton remained on the scene — and in San Francisco — in the period between his insolvency and his installation as Emperor.

One of these three traces is an historical “rescue” — reported by Allen Stanley Lane in his 1939 biography of Emperor Norton but apparently forgotten and possibly never documented before now.

The other two — including the Manifesto — are, we believe, discovered, documented and published here for the first time.

This new information should put to rest the conventional wisdom that Joshua Norton "disappeared" for X number of years only to "reemerge" fully transformed on a beatific day in September 1859.

No, there was a process and a path from fall to rise — from Point A to B.

These are three more of that path's public signposts.

Learn more here.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...