Of Medals and Medallions: Four Artifacts of Mid-20th-Century “Norton Culture”

And Some Dots That Connect Them to One Another and to the San Francisco Chronicle

EVEN THOUGH they were not “legal tender,” the promissory notes that Emperor Norton sold between 1870 (perhaps earlier) and his death in 1880 are some of the rarest and most fascinating examples of finely printed currency. There are only 40 of these notes known to exist. So, when one is offered at auction, it is big news in the numismatic world — numismatics being the study of currency and coin and numismatist being the word for one who does the studying.

One of leading networks for research and information about historical coin and currency — including news about auctions and private sales — is the nonprofit Numismatic Bibliomania Society. NBS publishes a respected quarterly journal, The Asylum. But, in many respects, the pulse of the organization is more readily felt through its weekly digital newsletter, The E-Sylum.

Every so often since 2015, E-Sylum has featured an article or discovery or event of The Emperor Norton Trust that longtime E-Sylum editor Wayne Homren thinks will be of interest to his readers.

In general, the Norton-related items that Wayne includes have something to do with the Norton notes. But, occasionally, he casts a wider net and posts about other Nortonian artifacts.

So it was that two years ago, in April 2018, I stumbled across an item in the 7 December 2014 issue of E-Sylum that featured these two photographs:

Medallion, 14K gold, 1953, created for the the San Francisco Chronicle — possibly in connection with the Chronicle’s Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt. Front and reverse views. Medallion struck by Shreve and Co. jewelers. Photographs © John Kraljevich. Source: Numismatic Bibliomania Society (here and here).

I was well aware of the San Francisco Chronicle's legendary Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt of the 1950s and ‘60s. And, a number of clues suggested to me that this 14K gold medallion was produced in that connection.

For those unfamiliar with the Hunt: Every year for a decade, 1953 to 1962, the Chronicle for several weeks published clues to the location of a “golden” medallion buried somewhere in the city. The lucky reader who found the medallion could bring it to the Chronicle's offices and receive 1,000 silver dollars — sometimes more, depending on the year.

The star-shaped medallion above, is embossed "1953" — the first year of the Hunt.

The piece was “struck for the S.F. Chronicle by Shreve.” Shreve & Co., the San Francisco jeweler, traces its Gold Rush origins to 1852.

And the artwork is very similar to the disembodied but jaunty “Norton head” that the Chronicle used to promote the Hunt in 1953.

:: :: ::

BASED ON these connections, I supposed this medallion to be the first of those buried for the Treasure Hunt.

But, a closer review of a photo gallery that the San Francisco Chronicle published in May 2018 for an historical web feature on the Hunt reveals something different. (The link is to an article — “When the Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt turned San Francisco upside down” — that is behind a paywall; but the gallery is free.)

Although the artwork on the 1953 medallion above features the "Norton head" that appeared in the Chronicle's promotions of the Hunt, the text — including the phrases "Grand Order of the West" and "Lady in Waiting" — is somewhat inscrutable and doesn't make any reference to the Hunt at all.

We’ll return shortly to the “Grand Order of the West.”

By contrast, as you can see in the photos (below) from the Chronicle's gallery, the buried star-shaped medallions feature a lengthy descriptive text about the "Emperor Norton Buried Treasure." And, the artwork is a vignette of the Emperor full-length, hand on his sword, Bummer and Lazarus at his feet.

The buried medallions are fairly large 19-pointed stars. According to the Chronicle, these medallions were 7 inches in diameter. Text on each medallion calls it a "plaque." (The live-action “contest medallions” were plastic — so as to make them impervious to metal detectors and put all competitors on a level playing field, armed with nothing but shovels, spades and their native smarts. Winners were presented with commemorative bronze versions of the medallions that, like the “Grand Order of the West medallion shown above, was made by Shreve.)

By comparison, the 1953 "Grand Order of the West" medallion is a 16-pointed star that appears to be a smaller, "handheld" piece.

One photograph in the Chronicle's gallery indicates that the paper threw a special "Emperor Norton dinner" in honor of the winner of the Hunt.

Was the winner, on this occasion, given the smaller medallion as a keepsake?

Was induction into the "Grand Order of the West" an honor the Chronicle accorded to others, but the paper used this dinner as the occasion to present the medallion to honorees?

Did the Chronicle have a “Grand Order of the West” award, or society of some kind, that had no connection whatsoever to the Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt or to any Hunt-related dinner — the paper simply branded the award with Norton iconography?

:: :: ::

CURIOUS TO SEE if I could learn more about this “Grand Order of the West,” I let my fingers do the Googling and found my way to a December 2019 eBay listing for an undated chest medal (or ribbon medal) of equally mysterious provenance.

According to the (alas) now-deleted listing from seller tamsguy67 in Aliso Viejo, Calif. — the item sold for $86 — this medal is etched aluminum and is 7½” long and 3¾” wide, including the ribbon. This is almost comically large for something to be worn pinned to one’s chest. But, the silly size is fitting for a medal that also features images of pistols, prospecting tools and an animal skull — and is designated specifically to be worn by the “Grand Bingelmeister.”

The additional designation “Knight Companion” would seem to link this medal to the 1953 Grand Order of the West medallion pictured above, which also includes a title of courtly nobility: Lady in Waiting.

:: :: ::

UNLIKE the 1953 Grand Order of the West medallion — which has “struck for the S.F. Chronicle” embossed on the medallion itself — the undated Grand Order of the West medal, which is blank on the back, doesn’t carry the name of the Chronicle in any way.

But, the medal’s Emperor Norton artwork may conceal a Chronicle connection — one that brings us full circle.

We started with images of the 1953 medallion that appeared in the Numismatic Bibliomania Society’s E-Sylum newsletter of 7 December 2014. The medallion belongs to a John Kraljevich.

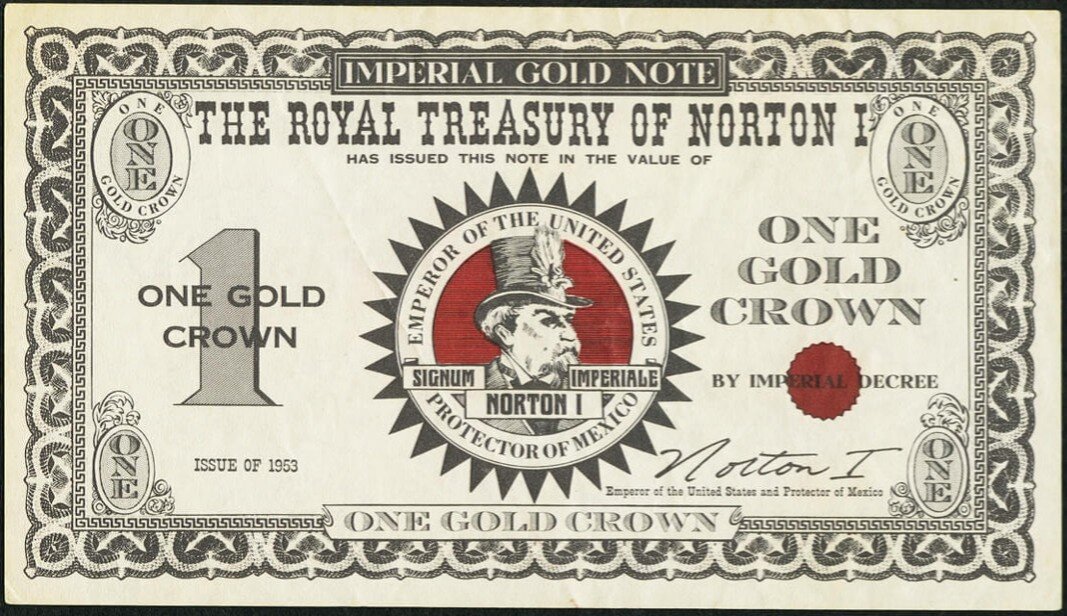

Kraljevich sent in the images as a response to a 23 November 2014 E-Sylum item (republished from another numismatic magazine; page 46, here), in which a Neil Shafer asked about a souvenir "One Gold Crown" note, also produced in 1953 and also — like the medallion — carrying the name of the San Francisco Chronicle (logo on the back)

One Gold Crown note, Royal Treasury of Norton I. Promotional souvenir, San Francisco Chronicle, 1953. Source: Heritage Auctions.

These notes were given out by the thousands — primarily to children — at the Chronicle’s Thanksgiving Day Balloon Parade in 1953, where the Grand Marshal was "Emperor Norton," as played by an impersonator. Remember that the Chronicle had just launched its Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt a few months earlier, so the paper was in High Norton mode.

Some of the notes were inscribed with a second signature, “N. Rex I,” in addition to the printed one. A child lucky enough to get one of these special notes could redeem it at the Chronicle’s offices for ten silver dollars. Children could redeem any of the notes for single rides at Playland-on-the-Beach, a popular San Francisco amusement park of the day, between 19 December 1953 and 3 January 1954 during that year’s holiday season.

“Emperor Norton” as the Grand Marshal of the San Francisco Chronicle’s Thanksgiving Day Balloon Parade, 1953. Photograph: Bill Young / The Chronicle. “San Francisco’s Forgotten Thanksgiving Day Balloon Parade,” SFGate, 27 November 2019. Source: San Francisco Chronicle.

But, notice the Emperor Norton artwork on the front of the note. It’s the same as on the Grand Order of the West ribbon medal — down to the cameo presentation of the artwork in the same serrated circular frame, with text presented in a circular ribbon and in three text panels just under the Emperor’s face.

The dealer who listed the medal on eBay hazarded a guess that it was from the 1930s. But, the mirroring of artwork between the medal and the Chronicle’s 1953 souvenir note raises the possibility that the two items were produced around the same time.

Certainly, it's possible that the medal was not produced in association with the Chronicle and/or that it was produced earlier (even significantly earlier) or later than 1953.

At a minimum, though: Given that the medal and the 1953 souvenir note used the same Norton artwork, one has to conclude that the artist-designer of one of these pieces knew about — and borrowed from — the art and design of the other piece.

The existence of the 1953 Grand Order of the West medallion that makes the connection to the San Francisco Chronicle explicit, together with the shared art and design motifs of the Grand Order medal and the Chronicle’s 1953 souvenir note, would appear to put both of the Grand Order pieces and the souvenir note in the Chronicle’s column.

The Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt medallions would make it a four-sweep for the Chronicle.

These all come together as a constellation of Norton-cultural associations, even if the dots don’t — yet — reveal a whole picture.

:: :: ::

UPDATE — 18 April 2020

Taryn Edwards, an Advisor to the Trust, was curious about the special dinner depicted in the photograph above. According to the caption the San Francisco Chronicle ran with the photo in its May 2018 web feature on the Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt, the dinner took place in 1959.

I did a little digging and was able to discover that the dinner was held at Ernie’s, the legendarily decadent and posh North Beach restaurant, on 12 May 1959. (Ernie’s closed in 1995.) Details of the evening are in a front-page article the Chronicle ran the next day under the headline “Norton's Nobles Recall Golden Past." The article continued on page 7 under the header “Norton’s Nobles Hold a Feast.” PDFs for page 1 and page 7 are here and here. (The year before, in 1958, meticulous re-creations of Ernie’s had starred in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Some frames from those scenes are on view here and here.)

As it turns out, the dinner was for all (and their respective spouses) who had discovered the buried medallion in previous Emperor Norton Treasure Hunts, 1953 to 1958, and who in virtue of their achievements had been inducted into — wait for it — the Grand Order of the West. So, that solves that mystery.

A Chronicle item published on 10 May 1959 described this as an “annual banquet.”

Members of the Order all had been given tongue-in-cheek courtly names: “Marquis of the Marina,” “Knight of Ocean Beach,” “Countess of Aquatic Park,” and so on, reflecting the neighborhoods where they discovered their medallions.

Marquis of the Marina was Ashley Hollingsworth (pictured in the dinner photo), who discovered the medallion buried behind the Palace of Fine Arts in the original Hunt, 1953. His wife, Elizabeth Hollingsworth, is pictured to his right in the photo. Given that spouses were included in the dinners, an educated guess is that the 1953 Grand Order of the West medallion detailed above — with its less-specific “Lady in Waiting” designation — was a commemorative made for her.

Under this theory, the undated Grand Order of the West medal detailed above — with its equally unspecific “Knight Companion” designation — was made for the spouse of the person credited with discovering the medallion in that year’s Hunt. (Sidebar: Perhaps the swanky 14K gold medallions from Shreve & Co. were done only for the Hunt’s launch year?)

As to that wacky medal — which shares “cameo” artwork with the “One Gold Crown” souvenir notes distributed during the San Francisco Chronicle’s Thanksgiving Day Balloon Parade of 1953…

It appears that the artwork made its debut as the seal of a front-page Norton “proclamation” the Chronicle published on 23 November 1953, announcing the upcoming distribution of the notes. A PDF for this page is here.

All of this suggests that the undated Grand Order of the West “Knight Companion” medal was produced for the spouse of the person who discovered the medallion in an Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt sometime between 1954 and the Hunt’s final year of 1962.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...