Emperor Norton’s Residence, the Eureka Lodgings, Was Not Located (Exactly) Where You Think It Was

Analysis of New Photo Evidence & Historical Fire and Property Maps of San Francisco Confirms the ID of the Building — But Points to a Different Site Than Has Been Supposed for Some 25 Years

“Nice job of painstaking research and urban legend-busting.” —San Francisco historian Peter Field

EVERY PHOTOGRAPH tells a story.

But, the same photographs scanned to high resolution can tell the same story much more clearly — and even can change the story line entirely.

That’s one of the lessons that follows.

In an October 2020 article, I published the following rarely seen c. 1876 photograph by Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904):

View of the U.S. Sub-Treasury at 608 Commercial Street (north side), San Francisco, under construction, c.1876. Photograph probably by Eadweard Muybridge. Historic American Buildings Survey CA-1218. Source: Library of Congress.

The photograph depicts the 1875–77 construction of the U.S. Sub-Treasury on the Commercial Street site where the original U.S. Mint had stood before being replaced by the new (now “Old”!) Mint at Fifth and Mission Streets in 1874.

The site is on the north side of Commercial, between Montgomery Street (to the east) and Kearny Street (to the west). The view is to the southwest towards Kearny.

What makes this photograph significant for Emperor Norton studies is that, at the top right of the photo, one catches a tiny glimpse — a few doors down — of the east side of the Eureka Lodgings, where Norton is documented to have lived from somewhere between summer 1864 and summer 1865 and his death in January 1880.

At the time that I published the photo, the Eureka had not been thus identified — and, I believed it was the only photographic view of the Eureka captured during the Emperor’s lifetime.

As we will see shortly, this turns out not to be true.

:: :: ::

MORE BROADLY: In my 2020 article, I sought to offer a comprehensive summary of what I saw as the best available evidence for determining the ID and specific location of the Eureka Lodgings — a summary that still, at that time, amounted to a series of tantalizing clues and probabilities but few conclusive answers.

Key sources for the discussion were small, low-resolution versions of two later photographs that show additional views of the stretch of Commercial Street between Montgomery and Kearny where the Eureka was located.

Having started with photographs in my previous article, I continue with photographs in the first part of the present article, in order to confirm the visual identity of the Eureka building.

Following that, I move in the latter part of the article into a deeper investigation of the exact location of the building, using historical fire insurance and city block (property) maps.

We pick up with those two later photographs. I now am able to present large, high-resolution scans of these that offer much more information — and that facilitate more accurate dating of the photos themselves.

The first of these is this one [4500 px wide and 1200 dpi — click to enlarge].

View of north side of Commercial Street between Montgomery and Kearny Streets, San Francisco, early 1906. Photograph credited to Treu Ergeben (T.E.) Hecht (1875–1937). Photo #AAB–3457, San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, San Francisco Public Library. Source: SFPL

For some time now, the Union Shrimp building at left has been seen as a possible later incarnation of the Eureka Lodgings building. This largely hinges on two things: (1) the building answers to contemporaneous descriptions of the Eureka as having three stories, and (2) it shares an address with the Eureka: 624 Commercial.

But, there are other reasons, too, why this building should be regarded as a candidate.

To understand why, it helps to look at the other buildings in this stretch.

606/608/610 Commercial

Peeping in at the far right — east towards Montgomery — is the completed U.S. Sub-Treasury building.

612 Commercial

The small three-story building immediately to the west (“left”) of the Sub-Treasury building is 612 Commercial Street. This appears to be the building that the Morning Call newspaper moved into in 1863 after its previous digs in a wood building at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets were devastated by fire in November 1862. If so, then this also is the building where Samuel Clemens, the future Mark Twain, had a desk in summer 1864 and where Bret Harte worked as secretary to the superintendent of the Mint, which had executive offices in this building.

The journalist–historian Frank Soulé (1809–1882), too — FOT (Friend of Twain) and lead author of the landmark 1855 compendium The Annals of San Francisco — worked in this building when he briefly was editor of the Morning Call in 1869.

The Morning Call had left this building by 1871. And, by 1872, the building had a new tenant whose sign still appears on the front of this 1906 photograph: The Hebrew — a weekly newspaper for Jewish readers that had been founded in 1863 by its publisher and owner Philo Jacoby (1837–1922) and that was edited by Philo’s younger brother, Ernest Jacoby (c.1852–1919; conflicting dates).

In 1912, Ernest wrote about an encounter with Emperor Norton. But, it’s hard to imagine that both brothers were not very familiar with their imperial Jewish neighbor a few doors down.

Sign for newspaper The Hebrew, 612 Commercial Street, San Francisco, early 1906. Detail of photograph credited to Treu Ergeben (T.E.) Hecht (1875–1937). Photo #AAB–3457, San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, San Francisco Public Library. Source: SFPL

632/634 Commercial (previously 614/616)

Continuing west, it’s the 4-story building two doors up from the Sub-Treasury and two doors down from the from the 624/626/628 building that most clearly specifies the date of this photo. It’s the brand-new building of the A. Lietz Company — a manufacturer of nautical and surveying instruments.

The San Francisco Public Library has the photo we’re examining here as undated (“n.d.”). But, plans and contracts for the construction of this building were announced in newspapers and building trade journals in September 1905. And, multiple historical accounts note that the building was occupied and in use for only one month before being destroyed in the earthquake and fires of April 1906.

Given that there still is literal “construction paper” in the street-level windows, I’m dating this photograph as early 1906.

Street level of new A. Lietz Company building, 632/634 Commercial Street, San Francisco, early 1906. Detail of photograph credited to Treu Ergeben (T.E.) Hecht (1875–1937). Photo #AAB–3457, San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, San Francisco Public Library. Source: SFPL

Worth noting: This photograph is credited to Treu Ergeben (T.E.) Hecht (1875–1937). Hecht is known as a ubiquitous copyist of earlier photos and as someone who put his name on many photos that he did not take.

But, Hecht did also take his own photographs. And, the 1906 San Francisco directory lists him at the address, 2321 California Street, inscribed on this photo.

For purposes of discussion, I’m considering this a Hecht photo.

Also of note here: Moving “right” to “left” in the photograph, from Montgomery Street west towards Kearney Street, the street address numbers get higher. The Sanborn fire insurance map of 1887 shows a previous building on the Lietz site as 614/616 Commercial Street. The 632/634 address for the Lietz building reflects new numbering being implemented.

620/622 Commercial

The low, rough-hewn building sandwiched between the Lietz building to its east and the 624/626/628 building to its west is the William Meakin machine shop and model-making business.

630/632 Commercial

Peeping in at the “left” of the photograph — next door to the west of 624/626/628 — is a glimpse of 630/632 Commercial Street. This was a large 4-story building that housed a mix of apartments; businesses, organizations and clubs; and street-level retail. In the mid 1880s, shortly after the Salvation Army arrived in San Francisco, part of the building became a “barracks” for this organization.

Given contemporaneous and early historical descriptions of the Eureka Lodgings — including descriptions of where it was relative to its Commercial Street neighbors — our “focus building” here appears almost by process of elimination to be on the Eureka site.

As we move through this analysis, we’ll see that earlier photographs reinforce this.

But: Is the building in this 1906 photograph the one that housed the Eureka Lodgings? Is it the building where Emperor Norton lived?

One bit of evidence in the plus column: the Wing Sung & Co. ghost sign between the second and third floors. Wing Sung & Co was a shoe manufacturer that first is listed at 628 Commercial in Langley’s San Francisco directory of 1879. The directory was published in April 1879 — which probably means that the company arrived at 628 sometime in 1878, when the Emperor was living at the Eureka.

Something to look for in the earlier photographs: Do they show a building in this location that matches the one here: three stories, with a “five-wide” pattern of arch-top windows in the upper floors.

Let’s see!

:: :: ::

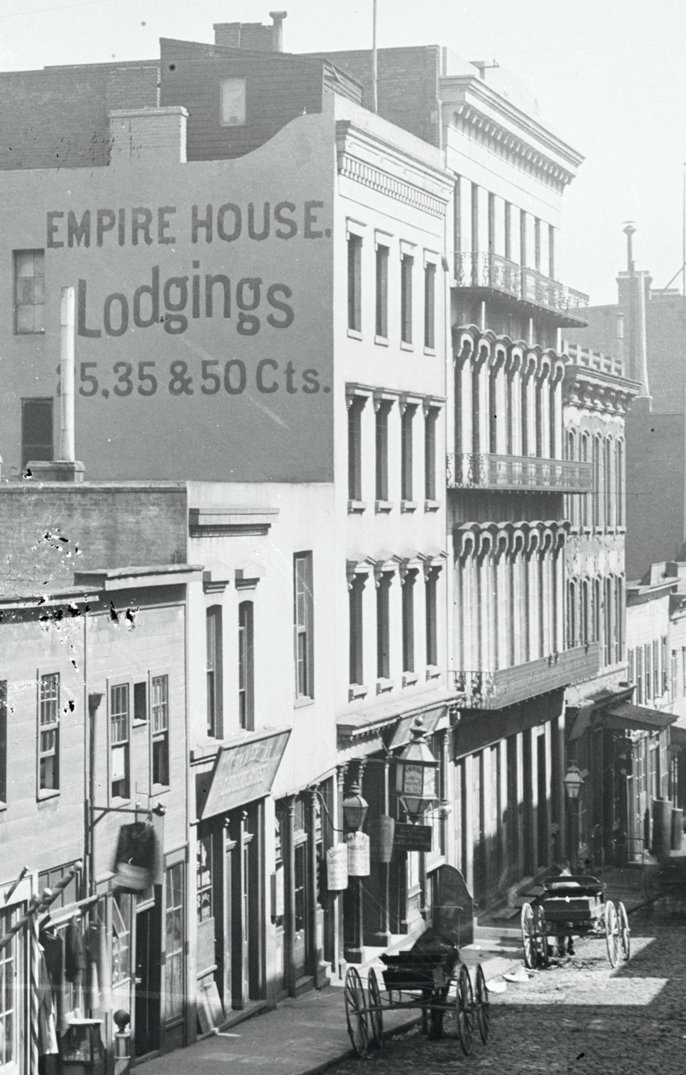

HERE’S A NEW high-resolution scan of the second of the two photographs that previously have featured in this discussion. The photo is credited to Allen Hancock Knight, Sr. (1854–1918). The view is looking east on Commercial Street from the west side of Kearny Street [3800 px wide — click to enlarge].

Looking east on Commercial Street from the west side of Kearny Street, San Francisco, c. 1892–94. Photograph by Allen Hancock Knight, Sr. (1854–1918). Source: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.588

The first order of business here is to date the photo. I was introduced to this photograph several years ago via the website of the late photo archivist Pat Hathaway, who dated the photo “circa 1888,” citing James Devine, who was a druggist on Kearny Street during this period.

OpenSFHistory, who provided the scan, dates it “circa 1880.”

Both are off, I think. But, Hathaway is closer. He just gets the wrong Devine.

Note the sign at the far left of the photo:

Detail of “John Devine, Druggist” sign in photo looking east on Commercial Street from the west side of Kearny Street, San Francisco, c. 1892–94. Photograph by Allen Hancock Knight, Sr. (1854–1918). Source: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.588

San Francisco directories of this period do list a James Devine working as a druggist on Kearny Street. But, his business was four-plus blocks south of the location shown in this photograph.

It’s a different Devine — John Devine — who directories list as a chemist, apothecary and druggist at the southeast corner of Kearny and Clay Streets (shown here) from 1883 to 1894.

On the sign, note the fragment “LVERT” below the fragment “[DRU]GGIST.”

Directories first list John Calvert in association with John Devine at this location in 1892. In the 1893 directory, Calvert remains at Kearny and Clay, and Devine is at a different location. In 1894, Devine is back at Kearny and Clay, with Calvert still clearly listed as the (new) owner.

In March 1895, the Los Angeles Herald noted that Devine “has purchased the Gillis drug emporium and taken possession." And, from 1895 on, Devine's name was not in the San Francisco directory.

I am dating this photograph c.1892–94.

Back to Commercial Street…

Towards the Montgomery end of the block, one can see the 4-story Sub-Treasury building. Moving west towards Kearny Street, the building of The Hebrew is visible next door, with the sign on the ledge between the second and third floors.

Continuing west, the 4-story Lietz building has not yet arrived.

The real interest here is in the three-building cluster that “starts” with the “Empire House Lodgings.”

Detail of photograph looking east on Commercial Street from the west side of Kearny Street, San Francisco, c. 1892–94. Photo by Allen Hancock Knight, Sr. (1854–1918). Source: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.588

The Empire House, closest to Kearny, had an address of 636 Commercial during Emperor Norton’s day. There was a reading room here, and this was where the Emperor stopped every morning to read the morning papers.

Next, moving east towards Montgomery, is a better view 630/632 Commercial, which we glimpsed in the 1906 photograph.

And then, next in the row:

Detail of 624/626/628 Commercial Street in photo looking east on Commercial Street from the west side of Kearny Street, San Francisco, c. 1892–94. Photograph by Allen Hancock Knight, Sr. (1854–1918). Source: OpenSFHistory / wnp15.588

This is the 624/626/628 building from the 1906 photograph: three stories, with a “five-wide” pattern of arch-top windows in the upper floors.

The only notable difference between 1892 and 1906 is that, by 1906, the top crown moulding has been lost. But, the building is the same.

Can we trace this building back further, to the Emperor’s day?

:: :: ::

IT WAS THE distinctive profile of the Empire House and the elemental shape of the three-cluster of Commercial Street buildings visually “anchored” by the Empire that came roaring back recently when I saw an image of a plate — an image that I’d seen many times before — of a panorama taken by Eadweard Muybridge in 1877, just a year after he took the construction photos of the Sub-Treasury on Commercial Street.

Here’s the image:

This is Plate 5 of an 11-plate 360-degree panorama of San Francisco that Muybridge shot from the top of the Mark Hopkins mansion on Nob Hill in 1877. The view is roughly to the northeast, with the east–west thoroughfare of California along the bottom right of the plate. St. Mary’s Cathedral, at California and Dupont Streets (the latter now known as Grant Avenue) is at center right. Yerba Buena Island is visible in the distance.

The three-cluster of Commercial Street buildings from the 1892–94 photograph — 636 (Empire House), 630/632 and 624/626/628 (Eureka Lodgings?) — is in the center of the orange rectangle:

The year after taking the 11-plate panorama in 1877, Muybridge returned to the Hopkins mansion in 1878 and took a new 13-plate panorama. This time, Muybridge used "mammoth" 18”x22” plates that were more than twice the size of what he had used in 1877 — and exponentially more capable of registering photographic detail.

Nick Wright of the Facebook group San Francisco History to the 1920s has what may be the world’s largest, highest-resolution scan of these 1878 Muybridge plates. Wright shared a few photo details from within the orange rectangle shown above. (These are from Plate 8 of the 1878 panorama.)

Here’s one. When Emperor Norton lived on Commercial Street — as he did when Muybridge took his 1877 and 1878 panoramas detailed here — the neighborhood was a hatter’s district. The “Hat Store” sign on nearby Montgomery Street speaks to that character.

Detail from Plate 8 of 13-plate panorama of San Francisco by Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904), 1878. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. Digitization and high-resolution scan by Nick Wright. Source: NYPL

Here’s a closer look from the same scan. The sign for “Clothing & Men’s Furnishing Goods” is the same one that appears in the Knight photograph from c.1892–94.

Although only the top floor of 624 Commercial is visible, one can see the “five-wide” pattern of arch-top windows in the upper floors that links this building to the one shown in the later photographs.

There is no doubt, really, that the building shown at 624 Commercial Street in the Muybridge panoramas of 1877 and 1878; in the Knight photograph from c.1892–94; and in the Hecht photograph of 1906 are one and the same building — the building that housed the Eureka Lodgings, where Emperor Norton lived from 1864/65 until 1880.

:: :: ::

WHERE WOULD one plot the former location of the Eureka Lodgings, 624 Commercial Street, on a map today?

This is where things get even more interesting!

Ask anyone in San Francisco who is tuned in to the Emperor Norton story, and the answer you’re most likely to get is Empire Park, the tiny POPOS (privately owned public open space) at 642 Commercial.

This association may trace its origins to the Barbary Coast Trail, the historical walking tour that debuted in the late 1990s, when the park still carried the name it was “born with” when it opened in 1990: Grabhorn Park.

No doubt, many assume that the park was renamed in 2000 for Nortonian reasons. In fact, the park was renamed for the concern, the “Empire Group,” that was the developer of the nearby commercial tower, 505 Montgomery. The tower was approved on the condition that the developer create the park as a public-amenity offset.

In 2016, Yerba Buena Lodge No. 1 of E Clampus Vitus dedicated a granite plaque inside Empire Park stating that “On this site stood the Eureka Lodgings.”

But, there are good reasons to doubt that Empire Park is the modern site closest to the former site of 624 Commercial.

Recall that, in the Hecht photograph of 1906, there is a building sandwiched between the Lietz building at 632/634 and the 624/626/628 building: the Meakin machine shop building at 620/622.

After losing its 1906 factory building, the Lietz company rebuilt and opened a new factory building on the same site in 1907. In 1918, the company built an annex next door, on the lot that previously had been occupied by the machine shop. The two buildings are shown together in this 1918 photograph that appeared in the A. Lietz Company catalog for 1919:

A. Lietz Company factory building at 632/634 Commercial Street, San Francisco (1907) with new Lietz annex building at 640/648 Commercial (1918). Shown in Lietz catalog for 1919. Collection of the California State Library. Souce: Internet Archive

In the decade between the early 1930s and early 1940s, the annex building was occupied by the Grabhorn Press — hence, the name Grabhorn Park.

Today, it is the site of Empire Park — and the park is located next to the 1907 Lietz building that still stands at 632 Commercial:

Here is a detail from the 1905 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map for this block of Commercial Street. The Commercial frontage (north side) is on the left-hand side of the map (adjacent to the number “73”); the right-hand side is the corresponding south Clay Street frontage (south side).

Detail from Sanborn Insurance Map for San Francisco, Sanborn–Perris Map Company, vol. 1 , pp. 27–28, 1905. Source: David Rumsey Map Collection

At the “top” of the detail, nearest Kearny Street, is 630/632 Commercial. Reading east (“down”) from there, we see that 624/626/628 Commercial — the building that housed the Eureka Lodgings — was 50 feet tall and that it extended all the way through to Clay Street.

Continuing east, we see three buildings and parcels between 624/626/628 and the Sub-Treasury building, 606/608/610 Commercial, at the “bottom” of the detail:

620/622 — Meakin machine shop building

[18634] — future home of the 1906 Lietz building

612 — offices of The Hebrew

A little less than a decade later, the 1913 Sanborn map showed how this stretch of the north side of Commercial Street (right-hand side of the block) was shaping up.

Detail from Sanborn Insurance Map for San Francisco, Sanborn Map Company, vol. 1 , p. 36, 1913. Source: Library of Congress

A few things worth noting:

612 Commercial — previously the home of the Morning Call and The Hebrew — was not rebuilt. The lot was incorporated into the building that had its main frontage at 615/617/619/621 Clay.

The 1907 A. Lietz Company building at 632/634 Commercial is mapped.

The Meakin machine shop lot next door to the Lietz building remains vacant.

The official block maps for this block produced by the City and County of San Francisco’s Office of the Assessor–Recorder have remained essentially the same for a century and more.

But, the earliest available map on the Office’s website, from 1935, bears out the basic arrangement that was in place by 1913. The main difference is that the Meakin machine shop lot that was vacant in 1913 now was occupied by the Grabhorn Press, who had purchased the 1918 Lietz annex building in the early 1930s.

Here’s the map:

Block 227 (including Commercial Street between Montgomery and Kearny), Block Maps, vol. 2 (blocks 160–315), San Francisco Dept. of City Planning, 1935, p. 71. Source: San Francisco Planning

Moving east to west, the relevant lots and their Commercial Street frontages are:

29 — McCoy Label Company (former Sub-Treasury) — 60 feet wide

46 — Mercantile American Realty Company — 20 feet wide

30 — A. Lietz Company — 35.5 feet wide

31 — Grabhorn Press (former Lietz annex) — 33.4 feet wide

43 — Marty family — 34.4 feet wide

42 — Ming Yee Association — 50.1 feet wide

So, what today occupies the site just to the west of the Meakin machine shop / Lietz annex / Grabhorn Press / Empire Park — the site where the Eureka Lodgings at 624 Commercial Street stood?

Bearing in mind what 624 looked like…

…it would be satisfying if the site now was home to this 1906 building at 662 Commercial Street that does read as a modern update of the Eureka building:

But — with all due respect to earnest and well-intentioned efforts over the last 25 years to turn Empire Park, at 642 Commercial Street, into a Nortonian pilgrimage site…

The photographic and insurance / property map evidence elaborated here leads me to conclude that the Eureka Lodgings, where Emperor Norton lived for the last 15 or so years of his life, was located on a site now occupied by the building next door to the west of the park: 650/652/654 COMMERCIAL STREET, built in 1910.

There is poetry here. Last March, the artist Niana Liu a.k.a. Misstencil (b.1976) spray-painted onto the east (park-facing) side of this very building her September 2021 stencil of Emperor Norton based on a c.1875 photograph of the Emperor by the Bradley & Rulofson studio. At the time, she painted the same stencil on a temporary plywood construction panel on the front of 632 Commercial. Liu’s intention was to “frame” Empire Park by placing Emperor Norton’s image on either side. In fact, she unwittingly was marking the historic site where the Emperor lived!

“Emperor Norton,” 2021, from San Francisco Icon series, by Misstencil. Originally stencilled September 2021 using this c.1875 photograph by the Bradley & Rulofson studio. This spray painting at 650/652/654 Commercial Street, San Francisco, done March 2022. Source: Misstencil

:: :: ::

A final note…

The next time you visit the San Francisco Historical Society, located at 608 Commercial Street behind the wonderfully preserved street-level façade of the 1877 U.S. Sub-Treasury building, know that the setback entrance passageway — narrowly framed by the Sub-Treasury to the east and the 1907 Lietz building to the west — is a “negative space” that outlines the original footprint and envelope of the old 612 Commercial Street.

Google street view of the gated entrance of the San Francisco Historical Society, at 608 Commercial Street, San Francisco. This space is within the former site of a building at 612 Commercial Street that housed offices of the San Francisco Morning Call, The Hebrew and the U.S. Mint — and the desks of Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Philo Jacoby and Ernest Jacoby. Positioned and cropped by John Lumea.

So, you may well encounter the ghosts of Mark Twain, Bret Harte, Frank Soulé and the Jacoby brothers as you enter.

Be prepared!

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...