The Snubs of 1934

This past Sunday, some 40 friends of Emperor Norton gathered to lay a special plaque for the Emperor at Home of Peace, in Colma, Calif. — the cemetery of Congregation Emanu-El, where the Emperor attended synagogue every Saturday.

This long-overdue gesture was prompted, in large part, by the fact that, although Emperor Norton was Jewish, he never was given Jewish funeral or burial rites. Not in 1880, when he died and was buried at the Masonic Cemetery in San Francisco. And not in 1934, when his remains were exhumed and reinterred at their present resting place, Woodlawn Memorial Park in nearby Colma.

The plaque is intended — as The Emperor's Bridge Campaign* put it in our original announcement of the plaque-laying ceremony — "to help mend this historical tear in the fabric of Emperor Norton's story."

Given the Emperor's complicated relationship with his own Jewishness, one cannot necessarily conclude that the Jewish community's failure to claim him in 1880 and 1934, by giving him Jewish rites, was an outright "diss" — or even that it was an unmitigated "failure." In 1974, the eminent rabbi and professor, William M. Kramer (1920-2004) — who said Kaddish over Emperor Norton's grave in the early 1970s — published a brief empathetic study, Emperor Norton of San Francisco, in which he left this parting thought:

One can only speculate that the Jews of San Francisco were embarrassed by the eccentric Norton. They knew themselves to be a community which merited being taken seriously. Perhaps they could not see themselves as being associated with the monarch of madness. There must be some reason why this born Jew who never joined any other religion was not given the customary rites of Jewish burial by his fellows. Perhaps, however, there is another interpretation.

In a brief item in "The American Israelite" in 1869 there is some indication that far from ignoring Emperor Norton, the Jews of San Francisco may have withheld their services in order to honor his wishes. Of Norton, it was said:

"He entirely ignores his Hebrew origins, arguing with due regard to logic, 'How can I be a Jew, seeing I am so nearly related to the Bourbons, who it is very well known were not Jews?'"

Depending upon how you read history, Emperor Norton's non-Jewish burials either are or are not blemishes on the truly great character of the San Francisco Jewry of his realm. Either they didn't do their Jewish duty or they respected his fantasy to the end.

:: :: ::

IT WOULD APPEAR that there is much less room for interpretation in the treatment that the Emperor experienced at the hands of two other major groups in 1934. At least, that's how Ernest Wiltsee saw it.

First, some history. According to Masonic records, Joshua Norton was inducted as a member of Occidental Lodge No. 22 of the Freemasons sometime between May 1854 and May 1855. This was about two years after the ill-fated rice deal of December 1852 that set Joshua on a very different path.

Indeed, it was in October 1854 — right around that time that Joshua was admitted into the Masons — that the California Supreme Court handed down its final ruling against him in his appeal to void the rice contract. Joshua was ordered to pay the Ruiz brothers, the shippers with whom he had made the contract, $20,000 plus costs.

Four years later — sometime between May 1858 and May 1859 — the Occidental Lodge suspended Joshua for failure to pay dues.

Be that as it may, it was Masons — individuals, probably, rather than the Lodge itself — who, it appears, helped to take care of Emperor Norton by paying most of his small daily rents for the remainder of his life. Indeed, San Francisco Chronicle pop culture critic Peter Hartlaub recently unearthed from the paper's archives the following editorial from the monthly Masonic Mirror — reprinted in the Chronicle of 20 April 1872 — which offers a flavor of the tenderness with which the Masons continued to regard their brother:

EMPEROR NORTON.

The erratic individual known to San Franciscans and Pacific Coasters by the above cognomen, but in Masonry as Brother Joshua Norton, was formerly a member of Occidental Lodge No. 22, in this city. His name appears as No. 57 in seniority of membership. Members of the Order still remember him as a brother, and materially assist in his support, and will never allow him to suffer; and when death shall put a stop to the deranged mental machinery, they will lay him away as carefully as if he was a real Emperor; and his sleep will be far more peaceful, and his freed spirit will enter as exalted a sphere as if he had really worn a crown while on earth. The physical machinery may become deranged, the balance wheel of the mind become impaired, and all may "gang a gee" here, in this world of misfortune; but on the other side of the river is perfection of life, life without alloy, life unclouded, where, we have no doubt, Brother Norton will walk the streets of the New Jerusalem with a real crown of glory on his brow. We only wish that all were as harmless, and innocent of wrong as he. —Masonic Mirror.

"When death shall put a stop to the deranged mental machinery," the Masonic Mirror wrote, "they will lay him away as carefully as if he was a real Emperor." And so they did. Were it not for Joseph Eastland, one of "Brother Norton's" fellow charter members of the Occidental Lodge, Emperor Norton would have been consigned to a pauper's casket and a pauper's grave when he died in January 1880. Eastland was an executive and co-owner of two of the gas lighting companies that later merged to form the company now known as PG&E; he also was, in addition to being a Mason, president of an even more exclusive men's fraternity, the Pacific Club, which, following an 1889 merger with the Union Club, became the present-day Pacific-Union Club. In other words, Joseph Eastland had plenty of money — and plenty of close friends with money.

Upon Emperor's Norton death, Eastland drafted and distributed amongst his circle a prospectus that quickly raised the funds for a handsome rosewood and silver-trimmed casket. And he donated one of his own plots in the Masonic Cemetery for the Emperor's burial.

:: :: ::

ALL OF THIS is the backdrop for what happened in 1934. And what a difference 54 years made.

In 1934, Emperor Norton's casket and remains were exhumed from the Masonic Cemetery as part of the city-mandated "mass eviction" of San Francisco cemeteries that began in 1914; and he was reburied at Woodlawn Memorial Park, in nearby Colma, on 30 June.

Six months earlier, in January 1934, the Emperor Norton Memorial Association was formed to secure a grave plot, to raise money for a new headstone and to organize a proper reburial ceremony. Whether or not the Emperor's grave was provided with a headstone in 1880 — a matter of some some debate — there was no marker by 1934.

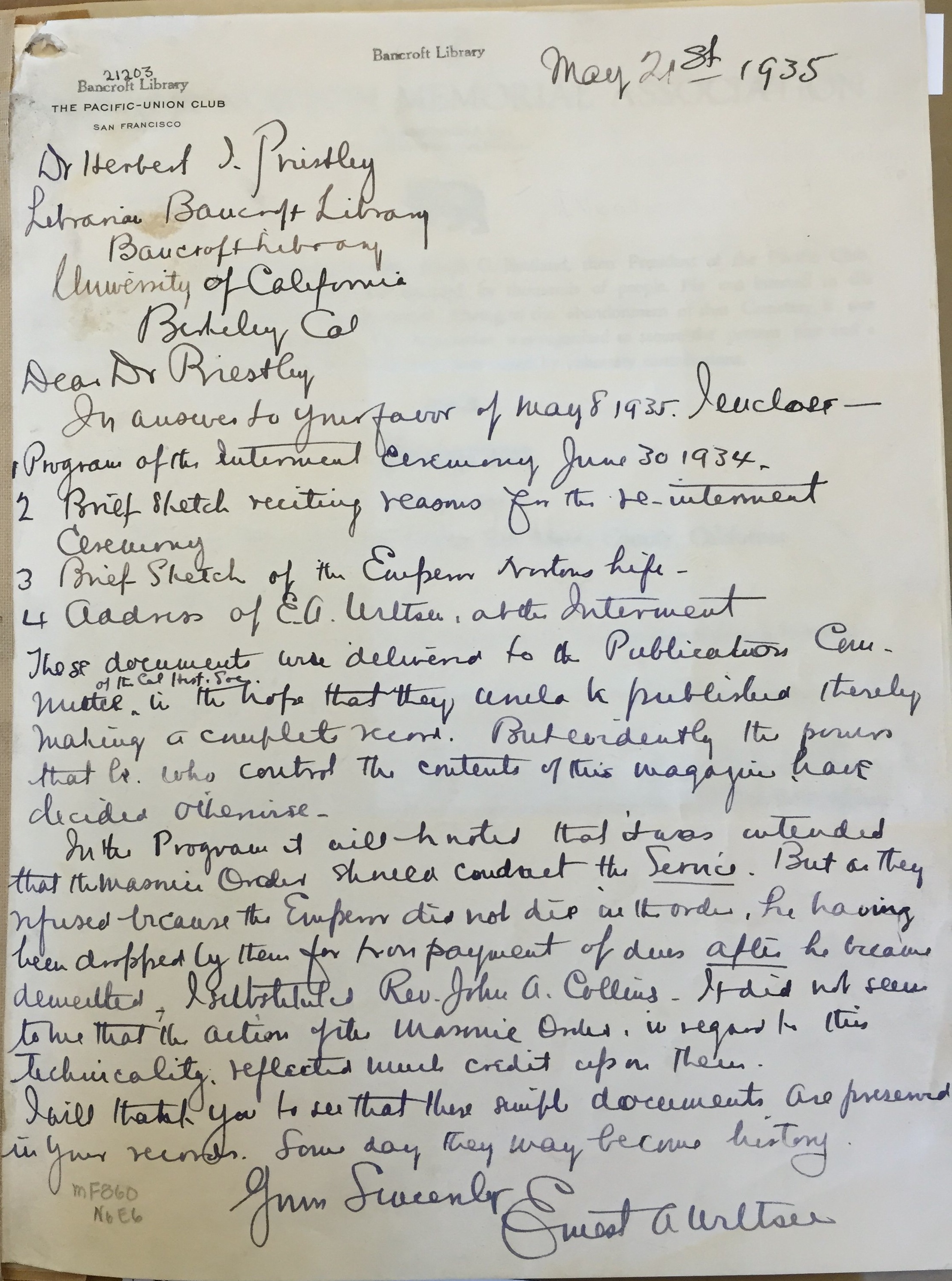

The president of the Association was the previously mentioned Ernest Wiltsee, who also was first vice president of the California Historical Society. It appears that, on 8 May 1935 — exactly 80 years ago today — Herbert Priestley, the Librarian of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, requested from Wiltsee documents related to the reburial proceedings. On 21 May 1935, Wiltsee sent Priestley the following letter enclosing the materials. Note that the letter is written on Pacific-Union Club stationery.

Letter from Ernest Wiltsee, president of the Emperor Norton Memorial Association, to Herbert Priestley, Librarian of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, 21 May 1935. Included in the Ernest A. Wiltsee Papers at the Bancroft Library. Photo by Joseph Amster. Published by permission of the Bancroft Library.

Dear Dr. Priestley

In answer to your favor of May 8 1935, I enclose —

1 Program of the interment ceremony of June 30 1934

2 Brief sketch reciting reasons for the re-interment ceremony

3 Brief sketch of the Emperor Norton's life

4 Address of E.A. Wiltsee at the interment

These documents were delivered to the Publication Committee of the Cal. Hist. Soc. [California Historical Society], in the hope that they would be published thereby making a complete record. But evidently the powers that be who control the contents of this magazine have decided otherwise.

In the Program it will be noted that it was intended that the Masonic Order should conduct the Service. But as they refused because the Emperor did not die in the order, he having been dropped by them for nonpayment of dues after he became demented, I substituted Rev. John A. Collins. It did not seem to me that the action of the Masonic Order in regard to this technicality reflected much credit upon them.

I will thank you to see that these swift documents are preserved in your records. Some day they may become history.

Yours sincerely,

Ernest A. Wiltsee

The Masonic farewell was to have been delivered by William Penn Humphreys, "Past Master of Occidental Lodge No. 22, F. & A.M." So confident, in fact, were Wiltsee and his fellow Association officers that Humphreys would participate in the reburial ceremony that Humphreys' name is printed in the program that was circulated on that day. Did Humphreys initially agree to speak then withdraw at the last minute? Whichever is the case, Wiltsee made his own sentiments on the matter clear in his letter to Priestley :

[I]t was intended that the Masonic Order should conduct the Service. But...they refused because the Emperor did not die in the order, he having been dropped by them for nonpayment of dues after he became demented....It did not seem to me that the action of the Masonic Order in regard to this technicality reflected much credit upon them.

Here is Wiltsee's copy of the program, with Humphreys' name rather determinedly scrawled out and Rev. Collins' name written over it. Evidently, the schedule didn't hold either.

Ernest Wiltsee's program from the Emperor Norton reburial ceremony at Woodlawn Memorial Park, Colma, Calif., on 30 June 1934. Included in the Ernest A. Wiltsee Papers of the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Photo by Joseph Amster. Published by permission of the Bancroft Library.

:: :: ::

PERHAPS even more baffling — not to say any more disappointing — than the Masonic snub of 1934 is the one from the California Historical Society, also mentioned in Ernest Wiltsee's letter:

These documents were delivered to the Publication Committee of the Cal. Hist. Soc. [California Historical Society], in the hope that they would be published thereby making a complete record. But evidently the powers that be who control the contents of this magazine have decided otherwise.

The "magazine" in question would have been the California Historical Society Quarterly, the predecessor to the journal California History, which now is published by the University of California Press "in association with" the Society.

In 1934 and 1935, there was no editor listed in the printed Quarterly. But the members of the Society's "Committee on Publication" — presumably the "Publication Committee" of Wiltsee's letter — were listed. So, who would "the powers that be who control the contents of the magazine" be, if not this Committee?

Here's the thing: In 1934 and 1935, five of the eleven people listed in the California Historical Society Quarterly as members of the Society's Committee on Publication also were April 1932 charter members of the revived Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus — a.k.a. the Clampers, the fraternal society that claims Emperor Norton as a patron saint. This included the Committee's chairman, Douglas S. Watson, as well as Charles P. Cutten, George Ezra Dane, Francis P. Farquhar, and Carl I. Wheat. Wheat and Dane had conceived the Clamper revival and, in 1931, had gathered at the Cliff House in San Francisco for an organizational meeting that also included Watson and Farquhar.

Wiltsee, too, was — in addition to being first vice-president of the California Historical Society — a charter member of the revived Clampers. And another member of the Society's Committee on Publication, and a member of the Society's Board of Directors, was Robert Ernest Cowan, who — while not, apparently, a charter Clamper — was the inaugural editor of the California Historical Society Quarterly and, in a 1923 issue of the Quarterly, had published his own brief essay on Norton, which remained extraordinarily influential in 1934 and 1935.

Other connections: The secretary of the Memorial Association, A.T. Leonard, Jr., was on the Board of the Historical Society. The vice-president of the Association, George Barron, was on a number of other official committees of the Society — including the Committee on Historic Names and Sites, which was chaired by Leonard and counted Wiltsee amongst its members. And George Lyman, a charter Clamper, was on the Board of the Society.

Finally: Allen Chickering — who actually was the president of the California Historical Society — was onhand at the reburial ceremony to lay one of three wreaths on the Emperor's new grave.

With so much sentiment for Emperor Norton at the highest levels of those "offices" of the California Historical Society responsible for determining the content of the Society's Quarterly, it beggars the imagination to contemplate how the proceedings of the Emperor's reburial did not find their way into the Quarterly's pages. Who were the "powers" that kept them out?

:: :: ::

WHAT IS STRIKING is the sheer pettiness of the snubs of 1934 — or, to put it another way, how precious little it would have cost the California Historical Society and the Masonic Order to treat Emperor Norton with a little kindness and respect. Presented with the opportunity to do otherwise, would these organizations treat the Emperor as shabbily in 2015 as they did in 1934? Let's hope not!

Perhaps there is cause for hope in the elegant words of Peter Evans, who was the Librarian of the California Historical Society when he wrote these words, in 1974, for the foreword of Rabbi Kramer's little book:

In James Thurber's "Fables For Our Time," there is a story titled "The Moth and the Star." This moth thought he could fly to a star, which was, as far as he knew, "just caught in the top branches of an elm." He never made it, of course; but it was a fine thought, and with persistence and the passage of time, he came to believe that he really had made it to the star. He lived to a ripe old age and died happy in the thought, while all his brothers and sisters, concerned with more practical matters in the vicinity of street and house lamps, had their wings singed and were worn out and died early. The moral of the tale is that he who flies afar from this sphere of sorrow is here today and here tomorrow.

So it is with Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico. His presence is with us....Joshua A. Norton was a legend in his time, and is still. Indeed the stories of his reign have survived a century, which places them, according to some authorities, in the realm of the classic, and according to others, in that of a bore.

What is boring, if it is boring, is that Emperor Norton has always been treated as a joke.

Indeed.

* In December 2019, The Emperor's Bridge Campaign adopted a new name: The Emperor Norton Trust.

:: :: ::

UPDATE — 4 September 2025

On 3 June 2025, after 166 years, California Lodge No. 1 of Free and Accepted Masons — the oldest Masonic lodge in California, founded in 1848 — reinstated Joshua Norton as a Mason and forgave all unpaid dues.

The story of this homecoming is in our September 2025 article here.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...