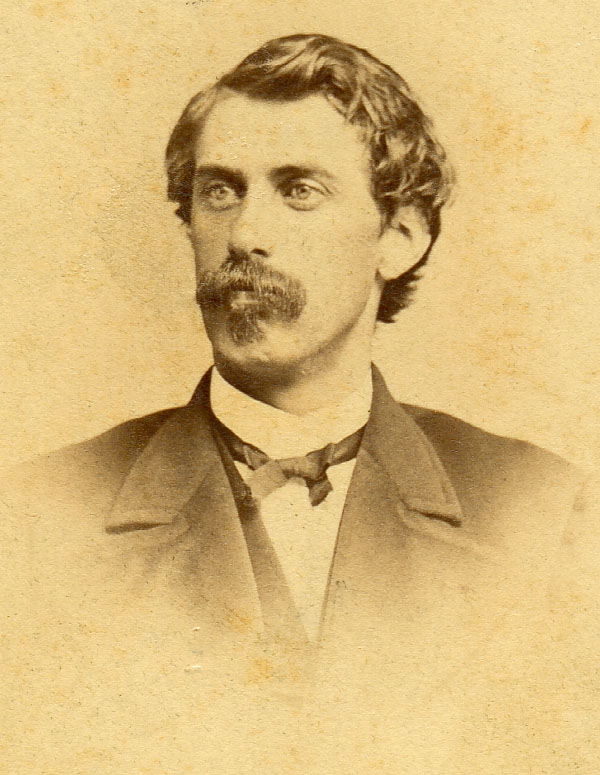

Palmer Cox's "Emperor Norton"

Palmer Cox (1840-1924). Photograph: Nahl Brothers, Artists, San Francisco, c.1865-71. Source: James Dalton Collection of the Grand Lodge of British Columbia & Yukon (Masons).

IN 1863 — the same year that Emperor Norton moved in to his longtime imperial digs at the Eureka Lodgings on Commercial Street — a young Quebec-born illustrator and writer moved to San Francisco.

His name was Palmer Cox (1840-1924).

Twelve years later, in 1875, Cox decided to move back east — to New York. By the mid 1880s, he was starting to become known for what became his greatest legacy: his children's comic strips that followed the exploits of fairy-like creatures that he called the Brownies.

Eastman Kodak liked the Brownies so much that, in 1900, it used them to market a new, inexpensive camera that became wildly popular.

The camera was called — what else? — the Brownie.

:: :: ::

BUT, WAY BEFORE all that, Palmer Cox was living in San Francisco, where he contributed illustrations and writing to publications including the Daily Alta California, the Golden Era and the San Francisco Examiner.

In 1874, toward the end of his "California period," Cox published his first book, a diary collection of Twain-like comic sketches and poems called Squibs of California, or, Every-Day Life Illustrated.

And illustrated the book was, with many pen-and-ink drawings by Cox, including a drawing of Emperor Norton that appears to have been intended as a kind of artistic coda to a story called "A Terrible Take-In."

The story relates an episode in which a restaurant proprietor in Vallejo, weary of being ripped off by "bummers" who reveal their inability to pay the bill after they've just had a full meal, devises a humorous scheme to thwart them.

Unlike most of the other drawings in the book, the illustration of Emperor Norton that immediately follows the story carries no caption. Alas, the title of the drawing in the book's List of Illustrations leaves no doubt as to the connection the reader is intended to make:

"Emperor Norton," (A Free Lunch Fiend)

Partial list of illustrations from Palmer Cox, Squibs of California, or, Every-Day Life Illustrated (Mutual Publishing Company and A. Roman & Co., 1874), p. xiii. Source: Internet Archive

But this oddly snarky caption belies the sympathy of the drawing itself (fig. 27, p. 69): A gentle Emperor Norton, slightly stooped, with his Serpent Scepter in his hand, a feather in his cap, a bristle on his nose and a sprig of flowers behind his back.

Perhaps the tenderhearted illustration, better than its mean-spirited title, better reflects the truth of how Palmer Cox saw the Emperor.

Isn't it lovely?

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...