Joshua Norton, Eternal Optimist

Across Three Months in 1853, the Future Emperor Norton Provided an Early Glimpse of the “Damn the Torpedoes” Approach That Would Enable and Define His Unlikely 20-Year Reign

First of Several Runs for Public Office

THREE THINGS that happened to Joshua Norton in the rice affair of 1853 and 1854 — more accurately, the cumulative effect of those things — marked the beginning of Joshua’s “translation” from San Francisco trader and merchant into…something else:

August 1853 — On appeal of the firm of Ruiz, Hermonos, California’s Fourth District Court reversed an initial decision in favor of Joshua Norton & Co. in the January 1853 breach of contract lawsuit of Ruiz v. Norton.

October 1854 — On appeal of Joshua Norton & Co., the California Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision in Ruiz v. Norton.

May 1855 — The California Supreme Court ordered Joshua Norton to pay Ruiz, Hermanos $20,000.

To be sure, the events themselves were significant in shaping the contours of Joshua Norton’s future.

Equally significant, however, are the things the Joshua did in anticipation — and in the wake — of these hammering events:

The California Supreme Court handed down its final decision against Joshua Norton on 10 October 1854. Within two weeks, Joshua had approached at least one newspaper, the Daily Placer Times & Transcript (of San Francisco) with plans for an ambitious project to build a seawall in North Beach — and had secured from that paper a friendly editorial, on 23 October 1854, that name-checked Joshua and made no mention of his saga in the courts. He continued to promote this project with ads over his own name through March 1855. (See my September 2023 article here.)

On 11 May 1855, the Daily Placer Times & Transcript reported the California Supreme Court’s order that Joshua Norton pay his adversaries in Ruiz v. Norton $20,000. Barely more than a week later, on 19 May 1855, Joshua offered himself as a Democratic candidate for City and County Tax Collector. (See my March 2022 article here.)

Later, two years after being forced to declare bankruptcy in August 1856, Joshua Norton in August 1858 declared himself an independent candidate for U.S. Congress. (See my March 2022 article here.)

In one way or another, the elected offices would have had money attached — so, it stands to reason that Joshua Norton’s motivation for running was at least partly financial.

But, the pattern here also serves as evidence of Joshua’s remarkable ability to compartmentalize his losses in real time — i.e., in a way that enables him, often without missing a beat, to seek increasingly public platforms in the face of increasingly public failures.

Joshua must have had some sense that his business and personal reputation was taking a series a major hits during this period — especially among those influencers whose support he would need if he was not only to run for public office but also to actually get elected.

And, yet, he was undeterred.

Or, to borrow from the modern campaign slogan of a certain U.S. Senator from Masachusetts: Neverless, he persisted.

:: :: ::

RECENTLY, I DISCOVERED an earlier example of Joshua Norton’s practice and pattern of making bold moves at the very moment when the facts on the ground argue for a more measured approach.

I believe that what follows is previously undocumented.

Recall that, in August 1853, the Fourth District Court handed down its decision against Joshua Norton & Co. in the case of Ruiz v. Norton. The decision was on August 29th:

Report of Fourth District Court decision (appeal) in Ruiz v. Norton, Daily Alta California, 31 August 1853, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Presumably, in the days and weeks ahead of the decision, Joshua knew from his lawyers that the decision was imminent — and that victory was not assured.

And, yet…

On 18 August 1853 — just a week-and-a-half before the Fourth District Court’s decision against Joshua Norton & Co. in Ruiz v. Norton — Joshua presented himself as a Whig candidate for California State Assembly (see paragraph 6):

Candidacy of Joshua Norton for California State Assembly in report of proceedings of Whig Convention, Daily Alta California, 19 August 1853, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

At the same time that the Fourth District Court rendered its judgment in Ruiz v. Norton, the Court also ordered that newly elected Sheriff William R. Gorham seize and sell “in front of the Court house door” two properties co-owned by Joshua Norton and his business partner William Sim: (a) a portion of 50-vara Lot 15, on the north side of Pacific Street mid block between Montgomery Streets and (b) 50-vara Lot 645, on the northeast corner of Bush and Taylor Streets.

Here’s the official notice that ran in the Daily Placer Times & Transcript for three weeks starting on 15 October 1853:

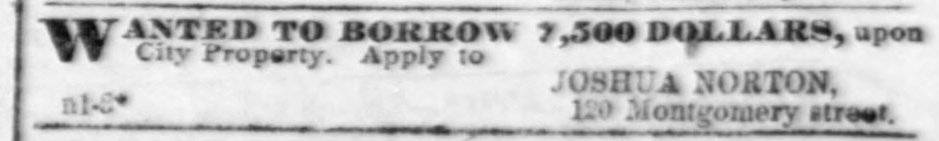

The sale was slated for 4 November 1853. So, it’s interesting to note that three days earlier — on November 1st — Joshua placed what appears to be a 3-day ad seeking a loan of $7,500.

Ad by Joshua Norton seeking loan of $7,500, Daily Alta California, 1 November 1853, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Joshua Norton’s placing a newspaper ad for a loan would suggest one of two things. Either (a) he already had been to the banks and been turned away, or (b) knowing the likely response from banks, he decided to take his appeal directly to the public.

Whichever is the case: Joshua’s urgent need for cash in early November 1853 — he had been paying lawyers for 9 months, but he would not be ordered to pay Ruiz, Hermanos $20,000 until 18 months later — reinforces my earlier observation that Joshua was overleveraged, and that such “wealth” as he had was mostly tied up in property: land, buildings, business equipment.

In short: Joshua Norton wasn’t very liquid.

Of course, given that he now was appealing the Judicial Court’s decision in the California Supreme Court, Joshua could have sought to reassure prospective benefactors that the rice contract dispute was “all a misunderstanding” and that he would prevail in the end. Still — as a loan applicant, Joshua wasn’t a good bet in November 1853. He must have known what a Hail Mary his “application” was.

A final question raised by Joshua’s ad seeking to “Borrow 7,500 Dollars”: The phrase “upon City Property.” Was Joshua referring to his own former properties that had just been confiscated by the City? Was he mounting a gambit to buy these back?

:: :: ::

LOOKING at how the limitations imposed upon Joshua Norton by the rice contract dispute of 1853–1854 unfolded — and at the ambitious ways in which Joshua repeatedly sought to break free of these limitations and chart a new course for himself during the longer “fallout” period of 1853–1859…

Some might be inclined to see Joshua’s actions as proof that he wasn’t living in the real world.

Others might say that Joshua simply was doing what he felt was necessary to survive in any given moment.

Still others might argue that Joshua is the one who made his messy bed — and that the fault is his, if he found the bed so difficult to lie in that he found himself wanting a new bed.

But — leaving aside this kind of moral judgment…

What were the qualities of mind and character at play in the choices and decisions Joshua Norton was making during this period?

One way to see it: The Joshua Norton of 1853–1859 is a case study in how the personal qualities of tenacity — and resolve ― and something like…hope were tested in ways that built up and strengthened the essential and particular brand of Resilience that made possible the Emperor Norton of 1859–1880.

One could go a step further to say that this was a “pioneer Resilience” — a Resilience shared by those who, like Joshua, made their way to San Francisco from great distances, and at great personal cost, in the late 1840s — and that this Resilience found one of many unique expressions in Joshua, later Emperor, Norton.

Under this theory, Joshua Norton’s actions of 1853–1859 demonstrated a Resilience that was already there — and that continued to be there after Joshua declared himself Emperor in September 1859.

Nearly every bold maneuver that Joshua attempted between 1853 and 1859 — promoting a public infrastructure scheme in 1854 and 1855; running for office in 1853, 1855, and 1858; even seeking a loan in 1853 — was “within the box” of the norms and expectations of business and civil society.

Joshua even served on a jury in September 1857 — and, this was after he was forced to declare bankruptcy in August 1856.

These facts push against the claim that Joshua Norton’s legal and financial blows of 1853–1856 created a decisive “break” that placed him on the “outside” after 1856.

Arguably, the “break” — if there was one — took place in 1859, with September 17th of that year being the date when Joshua Norton decided that it was time — finally — to try something completely new by declaring himself Emperor.

What bridged the “before” Joshua and the “after” Emperor was the Resilience — the eternal optimism — that had been there all along.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...