Emperor Norton Was Tuned in to Women's Suffrage Years Before He Signed an 1878 Petition in Favor of It

Discovery of Emperor’s Attendance at San Francisco Pro-Suffrage Meeting in 1871

New Details & Visual Documentation of 1878 Petition

IT LONG HAS APPEARED that Emperor Norton’s reputation for supporting women’s right to vote rests entirely on his having signed an 1878 petition advocating for the right.

As we’ll see, the Emperor had been looking at this issue for some time.

In fact, Emperor Norton’s take on women as political actors has been something of a minor footnote in historical accounts of the Emperor. The Emperor’s late-in-life signature in favor of women’s suffrage doesn’t come up in either of the major biographies of him — either Allen Stanley Lane’s in 1939 or William Drury’s in 1986. The handful of articles and one Master’s thesis that do mention it seem to be relying on a single source: a biographical article on the Emp, by Patricia Carr, that appeared in the July 1975 issue of American History Illustrated magazine (transcribed here).

Although a primary source was elusive, The Emperor Norton Trust initially included the Emperor’s support of women’s right to vote in our summaries of the Emperor’s policy positions, as it was consistent with his other commitments to equality, fairness, self-determination, and the common good.

We’ve continued to mention it, based largely on our discovery a few years ago of a line in an annotated California State Archives finding aid, Inventory of the Working Papers of the 1878–1879 Constitutional Convention.

In the chapter “Series Descriptions of Working Papers,” the section “Public Petitions and Memorials. 45 file folders. F3956:33-77” (starting on page 21 here) noted that

One women's suffrage petition from San Francisco contains the signature of Emperor Norton (box 3).

which pointed to the existence of a preserved document.

:: :: ::

WITH ONE THING and then another pushing it further and further down on my to-do list, I did not properly follow upon this research lead.

In effect, I “put a pin in it” until last week, when the issue caught my attention again and the online search “sesame” opened to reveal a digital copy of the petition in question — something I’d previously been unable to find.

Dated 10 October 1878, the petition was presented in Sacramento towards the beginning of the California Constitutional Convention, which formally opened two weeks earlier, on 28 September 1878.

The proposition was simple and concise:

To the Constitutional Convention in Sacramento, California, assembled.

The undersigned citizens of California, respectfully petition your Honorable Body to so amend the Constitution that no citizen of the State shall be disenfranchised on account of sex.

Text of San Francisco petition for women’s suffrage. 10 October 1878. 1878–1879 Constitutional Convention Working Papers. Courtesy of the California State Archives. Source: California Secretary of State (click “Document Type Index” — open “Public Petitions and Memorials” — and click F3956:47)

Some petitions were presented to the Convention on single sheets of paper as long as 10 feet or more. The overlapping of signatures in the California State Archives reproduction of this women’s suffrage petition, with signatures at the bottom of one digital “page” occasionally being repeated at the top of the next, suggests that the petition was among those presented on a single long sheet.

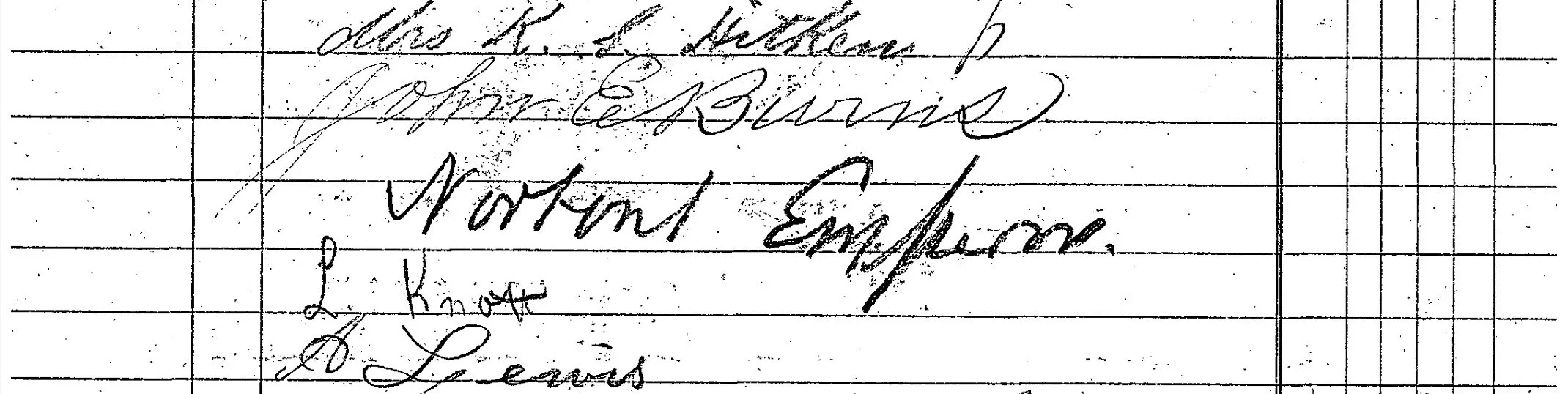

Here is a detail showing Emperor Norton’s bold signature on the petition — by my count, the 123rd signature of 221 signatures total:

Emperor Norton signature on San Francisco petition for women’s suffrage. 10 October 1878. 1878–1879 Constitutional Convention Working Papers. Courtesy of the California State Archives. Source: California Secretary of State (click “Document Type Index” — open “Public Petitions and Memorials” — and click F3956:47)

So, how was the Emperor first made aware of this petition?

It seems likely that the petition was circulated at one of the many lecture forums and political meetings the Emperor attended — and that this was where he signed it.

One intriguing possibility, though, is that Emperor Norton learned of the petition from one of the local leaders of the women’s suffrage movement — someone whose own signature is a little higher than the Emperor’s on the sheet: Addie Lucia Ballou (1838–1916).

Addie Ballou already was a noted suffragist lecturer and writer when she arrived in San Francisco in February 1874. Shortly thereafter, Ballou began to take art lessons. Going on to become a briefly noted portraitist, she painted the Emperor’s portrait in 1877.

Addie Ballou claimed that Emperor Norton sat for this portrait.

If so, did she and the Emperor discuss the women’s vote? Did she make sure that the Emperor signed the petition?

Here is Ballou’s signature:

Addie Ballou signature on San Francisco petition for women’s suffrage. 10 October 1878. 1878–1879 Constitutional Convention Working Papers. Courtesy of the California State Archives. Source: California Secretary of State (click “Document Type Index” — open “Public Petitions and Memorials” — and click F3956:47)

:: :: ::

MY “DISCOVERY” of digital documentation of Emperor Norton’s signature on the 1878 petition for women’s suffrage — documentation that probably had been available for some time — was a happy accident.

It was occasioned by my research to follow up on what may be my actual discovery…

Emperor Norton was attending pro-suffrage events AT LEAST 7 YEARS EARLIER — in 1871.

The fight for women’s right to vote arrived some 20 years later on the Pacific coast than it did on the East — with pro-suffrage lectures taking place on the East Coast starting in the late 1840s and in San Francisco starting in the late 1860s.

What was called a “convention” during this period was not only as we think of it now — a calendared annual gathering in a single venue lasting maybe 4 or 5 days max.

Rather, a “convention” could be called at any time and could last for several days or even some weeks in response to enthusiasm for the event — and it could be held across multiple venues, depending on availability.

The first large-scale San Francisco “convention” for women’s suffrage — signaling the maturity of a West Coast movement to recognize women’s right to vote — was in September–October 1869, at the Mercantile Library.

The second convention was held in January 1870 — primarily at Dashaway Hall but occasionally at the Mercantile.

The third convention took place 16–19 May 1871 at Pacific Hall, which was on the second floor of the California Theatre building, on Bush Street (north side) between Kearny and Dupont (now Grant).

Here’s the building in 1869:

California Theatre and Pacific Music Hall, c. 1869. By Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904). Collection of the Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley. Source: Bancroft

This convention was called by the California Woman Suffrage Association but — reflecting its regional aspirations — was styled as the Pacific Slope Woman Suffrage Convention, with speakers and representatives from Nevada, Oregon, and Idaho, as well as California.

The San Francisco Chronicle headlined all of its articles about each day’s convention proceedings “The Strong-Minded,” allowing the subheads to reveal the specific subject matter. Click on the image below for the paper’s full article of 19 May 1871 summarizing the sessions that took place on May 18th:

It is but a passing mention, but the Chronicle uses a section heading in this article to highlight that “Emperor Norton was present” at the previous day’s evening session.

:: :: ::

IS THIS the first or only women’s suffrage convention that Emperor Norton attended?

Certainly, it wasn’t his first or only exposure to the issue. The Emperor was an avid reader of newspapers that — early and often — covered suffragist lectures, meetings, and petitions from coast to coast. He was an habitué of the Mechanics Institute and possibly also the Bohemian Club, providing him with opportunities to converse with progressive-minded people who were following these developments closely. And he regularly attended lecture-and-discussion forums of reform-minded societies like the Lyceum of Self-Culture and the Radical Club — places where women’s suffrage was on the agenda.

An illustration…

Common Sense: A Journal of Live Ideas was a short-lived publication that had a regular section on Lyceum proceedings — and that even included as part of its banner the text “SPIRITUALISM, ITS PHENOMENA AND PHILOSOPHY, SOCIAL REFORM, WOMAN SUFFRAGE, ETC." [emphasis mine]. When Common Sense published a Proclamation by Emperor Norton in its issue of 1 August 1874, the Proclamation was preceded by a full-page write-up of the annual meeting of the California Woman Suffrage Society.

In fact…

The Emperor is documented to have attended at least one other event of the California Woman Suffrage Association — held on 27 July 1875 at the Young Men’s Christian Association building, 232 Sutter Street between Kearny and Dupont (now Grant). (For details and images, click on our Emperor Norton Map of the World pin here.)

Here’s how the San Francisco Chronicle noted the Emp’s attendance in the next day’s paper:

Excerpt from article, "The Women in Council; A Big Day for the California Woman's Suffrage Society," San Francisco Chronicle, 28 July 1875, p. 4. Source: Newspapers.com

All of this makes it a little curious that there has yet to surface a Proclamation in which Emperor Norton offers his take on women’s right to vote. The Emperor was not one to hold his peace on any subject that he deemed to be of social, cultural, political, or economic import.

If indeed Emperor Norton did remain silent on women’s suffrage, was it because he was ambivalent on the issue? Perhaps.

This much we know: By October 1878, the Emperor was ready to be counted among those working to empower women at the ballot box.

Good for him!

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...