Rosebuds for the Emperor, 1913

IT WAS SOMETIME after World War II that "Memorial Day" emerged as the favorite name for the United States holiday in which the living remember and honor those members of the U.S. military who have died while serving.

But, for decades before that, many people called this annual holiday "Decoration Day."

The name derived from the practice of placing flowers on the graves of the fallen — a practice that harks back to the ancient tradition of flowering the grave of anyone who is beloved.

That larger, more inclusive spirit was in the air for the Decoration Day that was celebrated in San Francisco on 30 May 1913. Based on the extensive illustrated coverage in the next morning's San Francisco Call newspaper, it appears that the 1913 event was conceived as the launch of a dedicated effort to raise the profile of Decoration Day as a more general holiday of remembrance.

In addition to the usual military commemorations — services at the Presidio and the casting of garlands on the waters of the Golden Gate — there was something like a public "tour" of the city's private cemeteries, starting at Mission Dolores and proceeding to the "Big Four" at Lone Mountain: Odd Fellows, Masonic, Calvary and Laurel Hill.

Those who have passed Norton 101 will recall that the Masonic Cemetery was Emperor Norton's resting place from the time of his death in 1880 until his remains were moved to Woodlawn cemetery, in Colma, in 1934.

In a section titled "Civilian Dead Are Also Remembered" (find the title highlighted in the scan of the original 31 May 1913 article here), the Call reported:

As the inauguration of a movement, which is expected to become an annual event in San Francisco, memorial services for the dead were held yesterday in each of the five cemeteries within the city limits. The Cemetery Protective organization had charge of arrangements, Mme. L.A. Sorbier taking active superintendence of the program at each of the burial grounds.

At none of the cemeteries was the gathered group large. Those assembled were mostly elderly people, with here and there the very young — grandfathers and grandmothers, accompanied by their children's children. But the groups were earnest and inspired with the beauty of the occasion.

The exercises were much the same in character in all the cities of the dead — a dirge or two played by Williams' military band, which participated in each of the programs; a prayer by one of the clergymen of the city, and one or two addresses by ministers or laymen. Then the little group that had charge moved on to the next cemetery.

Few Graves Undecked

Although the assemblages were as a rule rather small, there were many people in the various burying grounds, for nearly all who have dead buried in the city took advantage of the occasion to decorate the graves. Only here and there was a lonesome tomb overgrown with grass or half hidden under untended vines and shrubs, that was left without sprig of flower or more elaborate decoration. But it is the hope of the Protective league that as the years pass the custom of decorating all the graves will grow, so that in the end not even the tombs of the forgotten dead will be neglected.

"I hope," said Mme. Sorbier at Calvary cemetery, "that the day will come on the anniversary of this occasion, there will not be a grave in all of San Francisco but will have its covering of flowers, or at least one little sprig or blossom."

The Call went on to say that, in the Emperor's "neighborhood":

The Pioneer plat was the scene of the exercises held in the Masonic cemetery at 2 o'clock, the speakers being Rev. William Rader of Calvary Presbyterian church and William Hoff Cook. The committee in charge was headed by Mrs. M.T. Gamage. The speakers both dwelt feelingly upon the great deeds of the old pioneers who lay peacefully around them.

Author and anthologist Ella Sterling Cummins Mighels (1853-1934), the Gatherer of Literary California: Poetry, Prose & Portraits (Harr Wagner Publishing, 1918). Source: Internet Archive.

IT SEEMS that Ella Sterling Cummins Mighels was there that day in 1913.

Mighels was born near Sacramento and spent most of her life in San Francisco. She wrote a number of fictional works — including The Little Mountain Princess (1880), the first novel by a native Californian.

But Mighels perhaps is best known as an historian and anthologist of the work of early California writers, defining a "California Writer" as a writer "who is born here, or one who is re-born here."

In 1918, Mighels published her second California compilation, titled Literary California: Poetry, Prose and Portraits. The collection was punctuated by her own pieces, which she credited to "The Gatherer."

She was somewhat defiant about including these, writing in her introduction to the book:

If some of the writers protest that "The Gatherer" has included too many bits of unwritten history under the head "Life in California," I would admit the fact with the declaration that it is my privilege to preserve these things because of my birthright here. No one now living, probably, knows of these matters which I gleaned in my childhood. . . .Let others prepare and present a better book than this — but kindly let this be mine according to the conception that has dominated my mind from the beginning to the end.

One of Mighels' pieces relates her childhood memory of the Emperor — and her account of the lovely tribute that was repaid him on that Decoration Day five years earlier (view original at the Internet Archive here):

A Message from Emperor Norton I

Nothing in our early days was more charming than the sight of the poor throneless emperor in all his regalia, on parade on Kearny street with the rest of the fashionable world, stopping to present to some pretty little girl, the rose-bud bouquet from his coat-lapel. Everyone humored the harmless old man in his vagary that he was a person to be honored, and both mother and child would accept the proferred gift as from one of importance, and smile and bow in return and wish him "Good-day" most politely.

When death claimed the body of the man notable in our early annals as one whose loss of fortune had affected his brain, he was buried in the Masonic cemetery in the shadow of Lone Mountain's cross. But the memory remained in the hearts of those little girls to whom he had presented the flower from his breast as they passed in the crowded street. They never forgot him. When others tried to make mock of the story of his affliction, they always smiled and told of the pretty ceremony and how Emperor Norton had given them a flower to remember him by.

Years passed. A committee came into existence in 1913 resolved to visit the cemeteries on Decoration-day out in the neglected region of Lone Mountain and hold services there....They were led to view the spot where lay set apart by the Masonic Cemetery to mark the resting-place of Emperor Norton I. And to their surprise they found it already decorated by bunches of rose bud bouquets in memory of those he gave to the young away back more than a quarter of a century before. A silence fell upon them and they knew that he had builded better than he knew. Those little girls, now grandmothers, had not forgotten him.

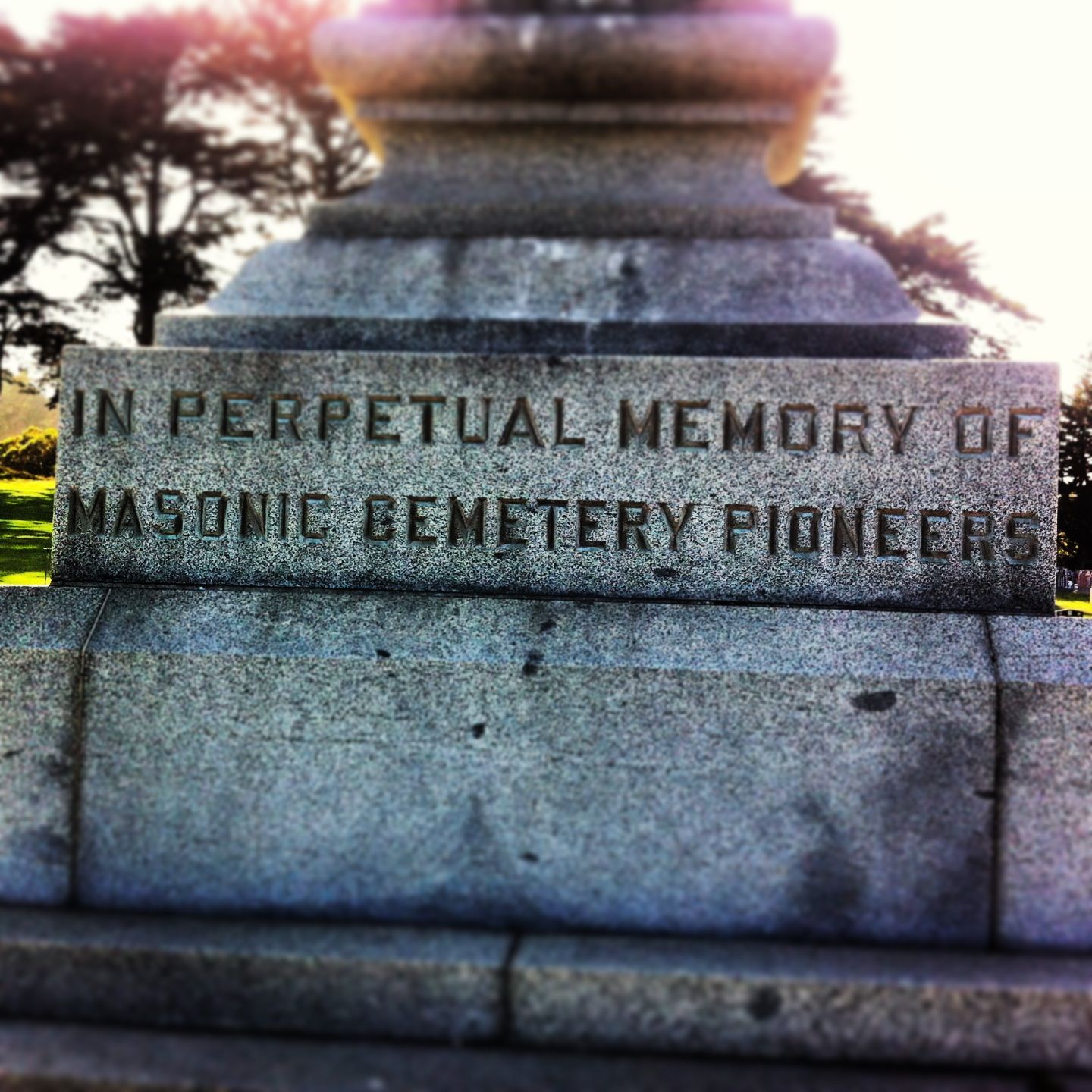

Masonic Cemetery monument at Woodlawn Memorial Park, in Colma, Calif. When he died in 1880, Emperor Norton was buried at the Masonic Cemetery in San Francisco, where he rested until his remains were moved to Woodlawn in 1934. As part of the great San Francisco cemetery eviction of the 1920s and 30s, most of the "residents" of the Masonic Cemetery found their way to Woodlawn, which originated as the new Masonic burial ground. Photograph © 2013 Bess Lovejoy.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...