1870s Forecasts of a Market for Emperor Norton Photographs & Signatures

IN 2016, BONHAMS auction house sold a c.1874 cabinet card of Emperor Norton for $6,000.

Listing showing 2016 sale of cabinet card photograph of Emperor Norton by the studio of Thomas Houseworth & Co., c. 1874. Source: Bonhams

The photograph was taken only a couple of years after an Oakland editor wondered, in January 1872, if people might actually pay for photos of the Emperor — and, if so, how much:

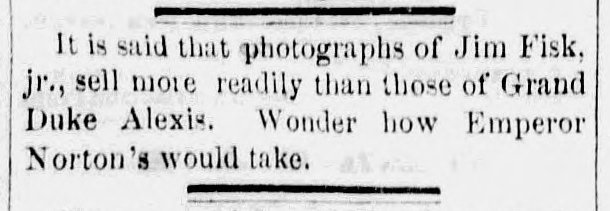

Item speculating on the possibility of a market for photographs of Emperor Norton, Oakland Daily Transcript, 24 January 1872, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

The Oakland Transcript’s point in mentioning James Fisk (1835–1872) would not have been lost on the paper’s January 1872 readers. Fisk was a New York robber baron whose business and personal exploits had been well-aired in the country’s newspapers. Fisk’s mistress Helen Josephine “Josie” Mansfield (1847–1931) had left Fisk for his business partner Edward Stiles “Ned” Stokes (1841–1901). After Fisk resisted a prolonged extortion gambit by Stokes and Mansfield, Stokes shot Fisk on 6 January 1872 — and Fisk died the next day.

As it happens, the c.1874 cabinet card of Emperor Norton that Bonhams sold in 2016 may have been the first commercially marketed “celebrity” photographic portrait of the Emperor.

There are earlier portrait-style photographs of Emperor Norton taken between 1864 and 1872 — but, these were smaller cartes-de-visite intended for personal use so probably were not sold in shops.

The outlier is Eadweard Muybridge’s March 1869 photograph of the Emperor astride a velocipede. A stereocard of Muybridge’s capture existed and might have been available for purchase. But, this was not exactly a portrait.

:: :: ::

WHAT DID Thomas Houseworth ask — retail — in 1874 for a cabinet card of his studio’s photo of Emperor Norton? One dollar? Two?

After 140 years, $6000 is quite an appreciation in value on one or two bucks.

But, it doesn’t begin to compare with the appreciation in value for Emperor Norton’s promissory notes that, typically, the Emperor originally sold for 50 cents.

The market value of these notes trades largely on the value of the Emperor’s signature.

In 2012, one of these notes, dated 1875, sold for nearly $13,000 — more than twice the auction sale price of the c. 1874 cabinet card:

Listing showing 2012 sale of 1875 Emperor Norton promissory note. Source: Heritage Auctions

A decade later, in 2022, a note dated 1872 sold for more than an astonishing $33,000.

Listing showing 2022 sale of 1872 Emperor Norton promissory note. Source: Heritage Auctions

No doubt, these prices would have shocked the editor of the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin who noted in November 1877:

Excerpt from editorial “The Value of Autographs,” San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, 8 November 1877. p. 2. Source: Genealogy Bank

A royal signature at $5 or less is cheap enough, but if the market were overstocked with such signatures, the price would be unfavorably affected. There is the signature of “Emperor Norton,” for instance, which is going at a low rate, and because of financial stress, is affixed to a great deal of scrip. But some day this autograph may be sought in vain by the collectors.

The observation is from an editorial, “The Value of Autograph,” occasioned by “a recent extensive sale of autographs in New York.” The sale included the signatures of Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, and other “revolutionary fathers”; John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and Ulysses G. Grant, among a larger group of U.S. Presidents; and a host of European monarchs.

That I have seen, this is the first and only instance in which an independent observer commenting during Emperor Norton’s lifetime identifies the Emperor’s signature on his promissory notes as a discrete element of value to collectors — possibly the primary element of value on the notes.

The Bulletin writer remarks on the ubiquity of notes signed by the Emperor. In a 2009 article published in the Brasher Bulletin, the monthly of the nonprofit Society of Private and Pioneer Numismatics — a rarefied group, to be sure! — the late Robert Chandler estimated that Emperor Norton sold some 3,000 signed promissory notes, roughly 6 per week for nearly 10 years.

Of course, these notes, with their signatures, wouldn’t be fetching $10,000–$12,000 at auction today — much less, three times that amount — if there still were 3,000 of them lying around.

The observer of 1877 notes that “if an autograph is rare and difficult to procure, it brings a large price, just as an old book in a pile of second-hand books will bring a round price if it is out of print and there is any demand for it” — and that “[a] dead man’s signature is more valuable in the estimation of collectors than that of a living man, just as the picture if a dead artist is enhanced in value, because the number of his paintings can never be increased.”

But, the writer was more prescient than he could have known, in hazarding that — notwithstanding the glut of Norton signatures in 1877 — “some day this autograph may be sought in vain by the collectors.”

The number of known examples today of promissory notes on “The Imperial Government of Norton I” that are signed by the Emperor? About 40.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...