The Houseworth Photographs

Perhaps it's the hat. But, if presented with a tabletop full of all the extant photographs of Emperor Norton (that we know of) and asked to play a game of "Which of these things is not like the other?", one might well pick this one.

The imperial trappings of sword and epaulettes are here, as they are in many other photographs of the Emperor. But, somehow — maybe a difference in tone conveyed by the jauntier, more casual feathered hat and the softer-fitting jacket — the effect, while certainly royal, is less "military" than it is Shakespearean. More dandy than soldier. More duke than emperor. Perhaps a sign that he still was working on his look.

At the bottom-right corner of the photograph, one can see part of the imprint of the studio: "Housew."

This is Thomas Houseworth and Co.

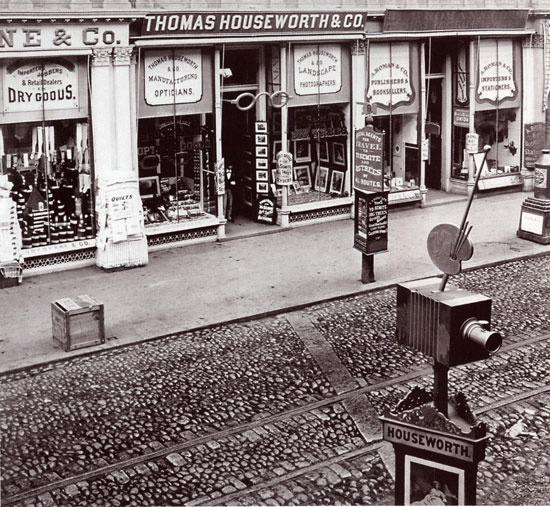

The storefront of Thomas Houseworth & Co., at 12 Montgomery Street in San Francisco, c.1873-74. Source: Society of California Pioneers.

According to David Shields, the McClintock Professor at the University of South Carolina, Thomas Houseworth (1828-1916) "ran a diversified studio that engaged in stereoscopic landscape work, society portraiture, celebrity publicity, and urban documentary photography employing a stable of operators with different specialties. Among the photographers who worked for Houseworth were William Evan James (1875-1881), Louis Thors, George Fiske (1872-73), Charles Weed (1864), Thomas Hart (1864-66), Eadweard Muybridge, and perhaps Carlton Watkins."

Shields's full brief on Houseworth is illuminating:

“An optical instrument maker turned photographer, Houseworth became the first important photographer of celebrities in San Francisco. Born in New York, he migrated to California in 1849 inspired by gold rush fever and spent two years prospecting before lack of success turned him back to lens grinding, the skill in which he had apprenticed as a teenager. Early in his prospecting days he teamed with George Lawrence, an optometrist trained by Benjamin Pike in New York City. In the summer of 1851, Lawrence and Houseworth, frustrated at the failure of their exploration of Trinity County, left the gold fields, formed a partnership and opened an optician’s office at 177 Clay Street. Houseworth later recalled that it was easier to get optical materials from New York than to secure a building in San Francisco.

Their first office was a two-story frame ‘tinderbox’ with a twelve-foot storefront and thirty-foot depth. Lawrence & Houseworth both manufactured lenses and frames and imported them. As an extension of their business Lawrence & Houseworth sold camera lenses and so became the focus of the community of California photographers. In 1859 the partnership began selling stereoscopic photographs produced by other firms. In the following year they turned publishers themselves, issuing the first of the famous stereoscopic views of the West. Houseworth took particular charge of the photographic survey of western scenes commissioning a circle of photographers for site images. The fame of these stereographic images was instantaneous, and made Lawrence & Houseworth the contact point for tourists visiting the West. (Houseworth served, for instance, as the San Francisco agent for Yosemite and the Big Trees resort in Calaveras County.) The paternership also garnered awards for photography in a host of exhibitions, the most noteworthy of which they advertised on the blazon on the back of their cabinet photographs.

In 1868 Lawrence retired from the partnership, leaving Houseworth in sole charge of both the optical and photographic businesses. Houseworth’s studio at 317 and 319 Montgomery Street became the center for a second stream of business: celebrity photography. Houseworth was a capable operator himself, but delegated much of his studio work to his staff, hence his designation of his studio as Thomas Houseworth & Company. In 1873 Houseworth opened his three story Art Parlor at 12 Montgomery. This became the site of portrait sittings. His organizational abilities and effectiveness as a publisher won him respect among camera professionals, expressed in his selection as first president of the Photographic Art Society of the Pacific organized in 1875.

Much is made by photographic historians of the cooption of Muybridge’s 1872 photos of Yosemite by Houseworth’s rival, Bradley & Rulofson, with suggestions that Houseworth may have bankrolled Muybridge’s trip to the site. While the contretemps produced some ugly talk in the papers and a spat in the courts, the affair did not lead to the decline of Houseworth’s business. Because of the preoccupation of historians with the scenic views, they have not noticed the redirection of Houseworth’s photographic work to his celebrity portraiture as the novelty of western scenery began to decline in the 1880s. The problem with Houseworth’s portraiture lay in the stiffness of his back paintings, which over the course of the 1880s began to seem increasingly primitive compared to those used by Henry Rocher and Max Platz in Chicago, Napoleon Sarony, Benjamin Falk, and Jose Maria Mora in New York, Gilbert & Bacon in Philadelphia, and Elmer Chickering and Charles Conly in Boston. In San Francisco, Houseworth’s former employee Louis Thors eclipsed him in the beauty trade.

Throughout the period of his activity as photographic publisher, he maintained an active practice as an optician. This business occupied his attentions with increasing force in the 1880s. By 1890 he had turned to optical work exclusively. In 1893 influenza struck him, and after a doctor pronounced a him a perpetual invalid, his embrace of physical culture brought him back to full health.”

Like other prominent photographic studios and publishers of the day, the Houseworth studio maintained a catalog from which one could request a commercial reprint of a photo of a favorite dignitary or entertainer or other public figure — perhaps in the form of a collectible "cabinet card."

The Houseworth catalog was called, simply, Houseworth's Celebrities. It stands to reason that all of the Houseworth photographs of Emperor Norton were in this book.

Via.

At least two others can be identified.

Recently, from the "back pages" of a MySpace profile for the electronic-experimental opera, I, Norton, by Bay Area composer Gino Robair, a thumbnail photo surfaced that appears to have been taken during the same sitting — or "standing," as the case may be — as the one above.

Finally — and evidently later in his imperial career, judging from his more-portly bearing — the Emperor was back in the Houseworth studio for a sitting that resulted in the following photograph, presented here as a cabinet card.

First, the back of the card, with Houseworth's elaborately decorated seal. Note the "TH" monogram anchoring the bottom of the seal:

And the front, with the Emperor's photograph, the caption — "Norton I. Emperor of the United States of America and Protector of Mexico" — and Houseworth's studio address at 12 Montgomery Street. (In the synopsis reproduced above, David Shields relates that Houseworth opened this location in 1873 — which tells us that the photo was taken sometime between 1873 and the Emperor's death in January 1880.)

A regal presence, indeed. Helped along, no doubt, by the beaver hat, but perhaps most accentuated by the fact that — of all the known photographs of Emperor Norton — this is the only one in which he is seated at a proper throne.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...