The Time Emperor Norton Lost His Platform But Kept His Dignity

Biographer William Drury Didn’t Have the Whole Story on the 1875 Incident That Unjustly Ended the Emperor’s Career at the Pacific Appeal

IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN on 15 November 1869 that Emperor Norton and Peter Anderson met and befriended one another.

The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution — recognizing that men of color, including those who previously had been enslaved, had the right to vote — had been passed by Congress in February 1869. The states had a year to deliberate and vote on ratification, and Anderson — the proprietor and editor of the Black-owned and -operated weekly The Pacific Appeal — gave a talk in favor of the Amendment. The Emperor was on the front row.

About 10 months later, in September 1870, Proclamations from Emperor Norton began to appear in the Appeal. The Emperor had grown weary of the increasingly common practice in which newspapers — the Daily Alta was an especially shameless offender — published fake decrees over his fake signature. He needed for his subjects to have the confidence that Proclamations published over his name really were from him.

So, on 23 December 1870, the Emperor issued the following Proclamation, which appeared on the front page of the Pacific Appeal on 7 January 1871.

Proclamation of Emperor Norton issued 23 December 1870, The Pacific Appeal, 7 January 1871, p1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Over the next 4½ years, The Pacific Appeal published some 250 Proclamations from Emperor Norton — easily four or five times more than any other single publication. This included many of the Emperor’s best-known and most important decrees insisting on the fair treatment of marginalized groups; calling out political, corporate and personal corruption; offering ideas on what constitutes a good society; and, of course, setting out the vision for what opened in 1936 as the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge.

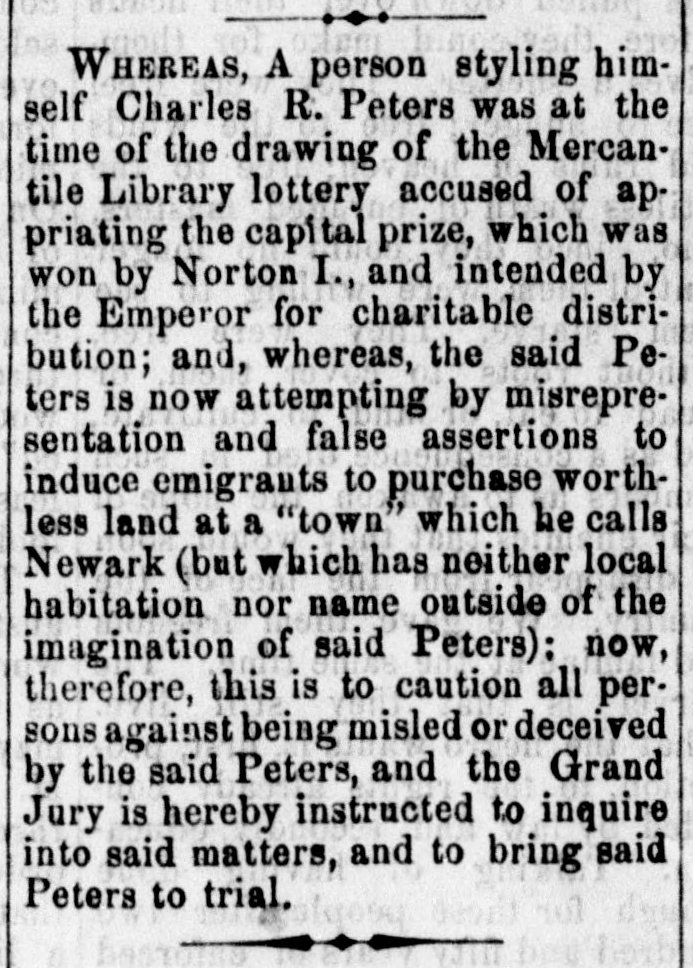

This all came to a clattering halt shortly after the following appeared on page 2 of The Pacific Appeal of 8 May 1875. Two signed Proclamations ran on the front page of the same issue. But, it’s this un-headlined, unsigned item that caused the stir:

Unsigned Proclamation of Emperor Norton, The Pacific Appeal, 8 May 1875, p2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

A couple of weeks and three Proclamations later — on May 25th — Charles Peters sued Peter Anderson for libel. In fact, Anderson was arrested — although he was quickly released on bail.

On May 29th, Peter Anderson published “A Retraction” in the Appeal, throwing Emperor Norton under the bus in the process. Not just giving the Emperor a stern public warning — as one might have expected, given the length of their association — Anderson actually cut the Emperor off, forbidding him from bringing any more Proclamations to the paper.

Anderson rounded out the retraction by laying a few flowers in Charles Peters’ path, calling Peters "the eminent and enterprising Real Estate Broker" and "an honorable, upright and enterprising citizen and gentleman.” For good measure, he even added some icing on top, finishing his apology by urging his readers to buy Peters’ Newark lots.

This last part is out of tune with Peter Anderson’s own stated philosophy of his paper’s appropriate sphere and no doubt is a reflection of how far Anderson believed he had to go to get out from under a lawsuit that, financially, he couldn’t afford to fight and that, as a matter of reputation, he — an esteemed Black man but a Black man nonetheless — couldn’t afford to lose. To wit: In an editorial, “Our Position as a Journalist,” that immediately followed the retraction, Anderson wrote:

For the dozen or so of years that we have been publishing the PACIFIC APPEAL it has been our endeavor not to go out of our way to discuss any measures or schemes inaugurated by our enterprising capitalists. We have strictly confined ourself to such current subjects or topics as concerned the political elevation of the colored race, of which we are identified, as well as the oppressed of all nations. This we have considered has been our legitimate sphere, and this only has been our mission.

And yet, just one sentence before this, Anderson ran a de facto advertisement for Charles Peters’ East Bay real estate gambit.

The retraction did the trick. Four days later, on June 2nd, Peters dropped the lawsuit.

Unclear is whether Peters had demanded Emperor Norton’s termination as part of a “deal,” or Anderson on his own had felt the need to go above and beyond in distancing himself from the Emperor.

It seems notable that, after the publication of the offending Proclamation on May 8th, Peter Anderson published three more Proclamations from Emperor Norton — one on the 15th, two more on the 22nd — before breaking with the Emperor on the 29th.

This suggests that although Charles Peters was offended by the Emperor’s Proclamation of the 8th, Peter Anderson was — at least initially — willing to let it slide.

Who knows? Perhaps, sometime in the couple of weeks before being served with lawsuit, Anderson did voice his displeasure to the Emperor in private.

Either way, it seems likely that it was the lawsuit that prompted Anderson to take such drastic action against the Emperor that he wouldn’t have considered otherwise.

:: :: ::

IN RELATING this incident, Emperor Norton’s biographer William Drury calls the Emperor’s take-down of Charles Peters “a grave mistake” — suggesting that the outcome was the Emperor’s fault and that he deserved what he got.

After excerpting Peter Anderson’s retraction, Drury concludes, somewhat glibly:

That was the end of His Majesty's happy association with Peter Anderson. Not that it mattered much; half a dozen papers, undeterred by the prospects of a libel suit, immediately began to compete for the honor of being the royal gazette.

Drury’s claim is not borne out by the seriously diminished number and frequency of Proclamations between mid 1875 and the Emperor’s death in January 1880.

Yes, Proclamations still were published. Yes, they might have been spread across a “half a dozen papers.” But, looking at the extant newspaper sources, Proclamations from Emperor Norton were much fewer and farther between than they had been for the 16 years previous, starting with his self-declaration of September 1859. And, the Emperor was nothing like as prolific during his later years as he was during the Pacific Appeal period from September 1870 through May 1875.

So, yes, “the end of His Majesty's happy association with Peter Anderson” did “matter much.”

Drury’s parting shot on this episode:

The Emperor, incidentally, was entirely wrong about Newark. Far from having "neither local habitation nor name outside the imagination of said Peters," Newark stands today on the east side of the bay, south of Oakland, a thriving salt-processing center with a population of about ten thousand.

In fact, it’s William Drury who “was entirely wrong about Newark.”

Newark, Calif. — down at the southeastern tip of San Francisco Bay — didn’t take off as any kind of salt-refining or manufacturing center until the early twentieth century. It wasn’t even incorporated until 1955.

Charles Peters may have put the area now known as Newark on the map of possibility. But, the Newark that Bill Drury saw and knew about when he published his biography of the Emp had precious little to do with Charles Peters.

In fact, Peters’ project of 1875 was a bit of a bust.

The truth is, Bill Drury — who has only a half-page’s worth of sentences to spend on the whole affair — is “curiously uncurious” about the question that lay at the heart of Emperor Norton’s “controversial” Proclamation of 8 May 1875:

Was the Emperor actually RIGHT about Charles Peters’ real estate scheme?

There is evidence to suggest that he was.

:: :: ::

IN THE LAST WEEK of 1874, the Newark Land Company — known more or less interchangeably as the Newark Land Association — began running ads announcing its plan to sell lots it had purchased in the area of the East Bay known as Newark, with a view to building a city there. The lots would be sold at public auction.

Especially in the first five months of 1875, the plan was aggressively marketed, with ads appearing nearly every day in the newspapers of San Francisco, Oakland and cities and towns all over Northern California.

The basic pitch was that, in economic terms, Newark was an ideally situated land flowing with milk and honey — and that only a fool who had disposable cash would fail to invest.

The president of the Newark Land Company was Charles Rollo Peters (1826–1881).* It was Peters’ name — and his name alone — that appeared on all the ads, with a handful of exceptions in which the names of the other Directors were added to his.

On 17 April 1875, the Oakland Daily Transcript announced a “[g]rand excursion from San Francisco to Newark on Sunday April 25th, given under the exclusive and peculiarly happy management of Charles R. Peters, Esq.” The Transcript — which went “all in” for the Newark plan, “puff”-ing Peters in the process — had been running Peters’ ads for the excursion for a month.

May 1875 saw the publication of the following elaborate ad for the Newark plan, announcing the date of the auction as 22 May 1875 and listing all the Directors — the people, including Charles Peters, who had opened their big wallets for this speculation early and who most needed for the auction to do well, so that they could get their money back and make some extra in the bargain.

Two things to bear in mind:

May 22nd was exactly two weeks after Emperor Norton weighed in with his May 8th Proclamation on Charles Peters and his Newark plan.

On May 22nd, Charles Peters had expressed no view of the Proclamation.

Here’s the ad announcing the auction:

On the morning of the auction, May 22nd, the Daily Alta did its promotional bit — calling Charles Peters “the irrepressible Charley Peters, the man of Nepoleonic [sic] ideas”:

“Sale of Newark Lots,” Daily Alta California, 22 May 1875, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

But, the auction went poorly. So poorly, in fact, that Peters stepped in to “adjourn” it before it was finished.

Reason? Even after five months of euphoric promotion, the prices were too low. Given the bids and the sales, Peters and his partners were not going to be able to make enough cash.

Here’s how the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin covered it later that day:

Three days later, on May 25th, the white Charles Peters sued the Black Peter Anderson for libel — ostensibly, because of a critical page 2 Proclamation that had appeared 2½ weeks earlier from the comparatively unempowered pen of Emperor Norton.

Seriously. Can anyone think that this ridiculous lawsuit was anything more than a rich, entitled, white asshole acting out about a bad sales day?!!

Four days later, on May 29th, Charles Peters resumed (and completed) his auction of Newark lots. Certainly, it was convenient for Peters that Peter Anderson published his retraction on the same day — even if the 29th also was Anderson’s first opportunity to do so, given that the Pacific Appeal was a weekly.

The coincidence of the auction and the retraction may help to explain why Anderson found it useful to include a plug for Peters’ lots.

:: :: ::

EMPEROR NORTON was not the only one who was on to Charles Peters.

While the Oakland Daily Transcript busied itself doing publicity for Peters, the Oakland Tribune took a more jaded view. In November 1875 — several months after the events that had come to a head in May and June — the Tribune ran the following item in which its San Jose correspondent, “W.H.,” related a conversation he had with a man on the train home:

“The Newark Fraud,” excerpt from “Oakland to San Jose,” report of San Jose correspondent, Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, 9 November 1875, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

The correspondent notes that Peters no longer was heading up the Newark Land Company. In fact: After incorporating in February 1875, the company held regular shareholder meetings. Following the September meeting, newspaper items appeared in early October reporting that the company had “incorporated” — apparently, re-incorporated — with an all-new slate of Directors, except for one non-U.S. holdover from London.

Surely, this turn of events — which carries the whiff of a shareholder revolt — was an index of how poorly things had gone for Peters in Newark.

Back in May — three days after Charles Peters sued Peter Anderson on the 25th and the day before his “second try” auction on the 29th — the thin-skinned Peters took out an ad in the Oakland Transcript in the form the following “card” that the Transcript ran on the 28th, 29th and 31st:

The Tribune took the unmistakeable hint: that Peters was preparing — or at least threatening — to sue them next. Here’s how the paper responded in its edition of May 28th:

Editorial responding to “card” from Charles Peters, Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, 28 May 1875, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Two weeks later, the Tribune still hadn’t heard anything from Peters’ lawyer — so they asked what was up, headlining with the name they had adopted to ridicule Newark and its salesman:

“From Mosquitoburg,” Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, 15 June 1875, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

If Peter Anderson had cause to be afraid of Charles Peters, the Oakland Tribune betrayed no signs that they had. If anything, the paper seems to have relished making sport of Peters. So, they were back at him in the next evening’s edition.

Of course, the point is that the gullible buyers are the “fleecy” sheep and that Peters is the one with the shearing scissors.

Item on the sheep-shearing Charles Peters, Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, 16 June 1875, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

To be fair, the Tribune had Oakland-based reasons for opposing the Newark project. In a 3 November 1875 editorial, the paper aired its suspicions that the larger point of the project was to improve rail links with San Francisco, undermining Oakland’s position as an economic hub.

But, it appears that the Tribune also really did believe that Charles Peters was a bit of a snake — and that his Newark “product” was better bottled up and sold off the back of a wagon.

:: :: ::

IT’S WORTH REMEMBERING who Emperor Norton — in his May 8th Proclamation — thought would be the most-likely victims of Charley Peters’ profit-making ambitions at Newark: immigrants.

The Proclamation reflected the expectation that, ultimately, it would not be current residents of the Bay Area and Northern California who bought, built on, and maintained most of the land and property at Newark. Rather, the real “marks” were immigrants flooding in from the East Coast and Europe.

The reconstituted Newark Land Company made this explicit, replacing Charles Peters with a non-Board manager, William Martin, who was head of a booster project known as the California Immigrant Union. In late October and early November 1875, the following item appeared in at least 10 California newspapers. Ostensibly an article, the item clearly was a press release, claiming that the Newark lots offered immigrant “farmers of small means” the opportunity to “lay the foundation of a permanent home, with the certainty of, at least, a competency, and, in all probability, fortune.”

The “blow-hard” Charley Peters may have been gone from the Newark Land Company in body — but, he still was there in spirit.

“Farmers of Small Means,” probably a press release from the Newark Land Association, Sacramento Daily Record–Union, 27 October 1875, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

A letter to the editor that appeared in the San Francisco Daily Evening Post in July 1876 bore out the Emperor’s warning more than 14 months earlier:

:: :: ::

PERHAPS THE MOST poignant “ripple” in this whole story is the one that arrived on 31 May 1875 — at the midpoint between

Peter Anderson’s May 29th editorial (a) retracting Emperor Norton’s Proclamation of May 8th and (b) “firing” the Emp himself — and

Charles Peters’ decision to drop his libel suit on June 2nd.

In William Drury’s 1986 account, Emperor Norton’s authorship of the May 8th Proclamation was only a “best guess” (my phrase). Looks like a duck, sounds like a duck. Must be a duck.

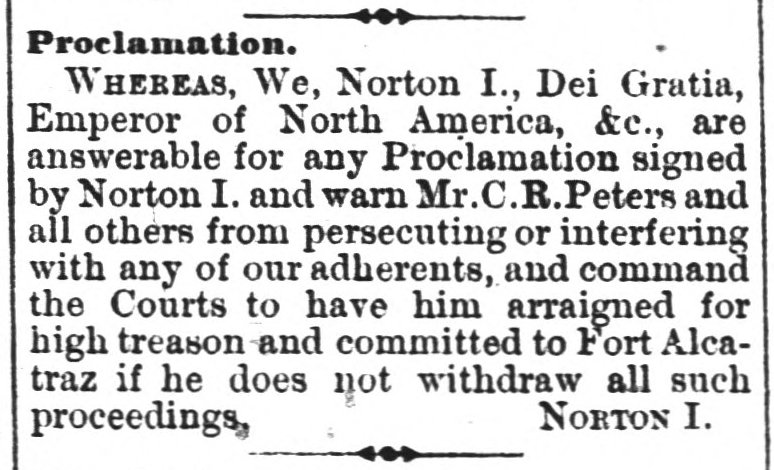

In fact: If there was any doubt at the time, the Emperor actually owned his May 8th Proclamation in a follow-up Proclamation that appeared in the anti-Peters Oakland Tribune on May 31st:

Proclamation of Emperor Norton, Oakland Daily Evening Tribune, 31 May 1875, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Apparently responding to multiple of the “dominoes” that had fallen in the wake of his unsigned Proclamation of May 8th — Charles Peters’ lawsuit of May 25th (which he had yet to drop); Peters’ “card” of May 28th; and Peter Anderson’s retraction of May 29th — Emperor Norton packed quite a lot into a few lines.

The primary messages of the Emperor’s new Proclamation would seem to be:

Although my signature on the Proclamation at issue did not make it to print, I did sign it. It is my Proclamation.

I stand by the Proclamation — and I alone am responsible for it.

Anyone who disagrees with the Proclamation is to bring their concerns to me directly.

Note to Peters and his lawyers: Leave Peter Anderson alone.

Clearly, Peter Anderson felt that he had no choice but to make his friendship / relationship with Emperor Norton dispensible — a casualty.

The Emperor seems to have had a different view — seeking to protect Anderson even two days after Anderson disparaged him and cut him off in public print.

This suggests that the Emperor knew what the real score was — the pressures that his old friend was under.

It also speaks volumes as to the character, the dignity and the nobility of the Emperor Norton.

Were Emperor Norton and Peter Anderson ever able to figure out a way to mend their personal fences — even if it no longer was possible for Anderson to be the Emp's publisher?

One can’t help but wonder — and hope.

* Charles Rollo Peters’ son of the same name — dates, 1862–1928 — became a respected oil painter.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...