Did San Francisco City Government Really Buy Emperor Norton a New Suit?

Oft-Repeated Claim May Have Its Origins in an Undocumented Line from a 1927 Booklet

“AND then there was that time….”

For nearly a century, those carrying forward Emperor Norton’s story — not all, but enough to make it stick — have included amongst their readily accepted and blithely repeated “greatest hits” the claim that, when the Emperor’s uniform became tattered, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the City’s elected government, bought him a new one.

If such a momentous thing had taken place, one would expect to see it contemporaneously documented in local newspapers of the day or in the official Municipal Reports of the City and County of San Francisco.

More about that shortly.

Over the last couple of decades, many online accounts of the Emperor — including the Wikipedia entry — have used the same sentence (or some very close version of it) to transmit this claim:

When his uniform began to look shabby, the Board of Supervisors, with a great deal of ceremony, appropriated enough money to buy him another, for which the Emperor sent them a gracious note of thanks and a patent of nobility in perpetuity for each Supervisor.

Almost always, this sentence is quoted blind and without documentation of the claim itself. In fact, the sentence is plagiarized from the one-page passage on Emperor Norton that appears in Herbert Asbury’s 1933 book, The Barbary Coast.

Asbury didn’t document the claim either — but, keep that phrase, “when his uniform began to look shabby,” close by.

During this same recent two-decade period — which is to say, the period since the December 2002 release of Martin Scorcese’s loose adaptation of Asbury’s most famous book, The Gangs of New York — there has been a reassessment of Asbury which amounts to a reality check on how reliable his accounts in his four-book “underground” series, including these two books and two others on Chicago and New Orleans, really are.

There is a new awareness of the fact that, in portraying the 19th-century crime worlds of his chosen cities, Asbury relied heavily on — and was not really interested in challenging — the highly fabricated and poorly remembered newspaper and personal accounts of the period.

To wit: Herbert Asbury was not functioning as an “historian” in the scientific and forensic sense in which we understand that term today.

On the occasion of a 2001 reprint of Gangs, Luc (now Lucy) Sante reviewed the book in The New York Review of Books, where she wrote:

Asbury was not a modern historian; he did little archival research, studied no graphs, did not inquire more than glancingly into immigration patterns or employment figures or variations in the price of wheat. He did, apparently, conduct some interviews for the later chapters, but mostly he just read. You can find his principal sources listed in the slender bibliography at the end. What he read were mainly partial and unreliable accounts: the highly colored nineteenth-century newspapers (as opposed to the dry sort, which devoted themselves to sermons and social notes); the memoirs of retired churchmen, retired crooks, retired cops; the fuzzy anecdotal collections of antiquarians. The newspapers had no fact-checkers and avoided libel suits by being vague on specifics of name and place. The retirees had fallible memories and even more fallible egos. The antiquarians collected and polished any stray bits of ephemera that blew their way, and those could range from the precise to the spurious.

You can follow a given story of Asbury’s through a chain of sources, from a romancer like Alfred Henry Lewis (The Apaches of New York, 1912) or a windbag like Frank Moss (The American Metropolis, 1897) back to the Police Gazette, ancestor of both the true-crime magazine and the supermarket tabloid, or to a pamphlet or a tip sheet or a broadside from even earlier in the nineteenth century, whose contents were likely improved, not to say invented wholesale, by their author or editorial staff of two or three Grub Street poets. Did the Old Brewery in the Five Points really average a murder a night for nearly fifteen years? Was Brian Boru really eaten by rats as he slept off a drunk in a marble yard? And what about all those dens of vice? Asbury reproduces the adjectives of the slummers who visited or perhaps just heard about them: they were “sordid,” “vile,” “depraved,” but what else? Maybe they did feature orgies worthy of the name, or maybe they were just as miserable, dirty, dank, and sad as the needled-beer joints photographed around 1890 by Jacob Riis, the first person to put substance to a century’s worth of horrified rhetoric.

This is not to say that Asbury was gullible. You will note that he puts no inverted commas, actual or figurative, around the stories concerning Mose Humphries, the city’s own Paul Bunyan, a Bowery Boy who was at least eight feet tall and could scratch his knee while standing erect. That does not, however, mean that Asbury believed that Mose could swim the Hudson in two strokes, or that he rescued becalmed ships by blowing his cigar smoke at their sails.

What most confuses the modern reader, though, is that questionable anecdotes coexist with matters of unimpeachable authority.

:: :: ::

BACK to Emperor Norton — and to the question of where Herbert Asbury got his information about the Emperor’s uniform.

As in The Gangs of New York, Asbury provides a “slender bibliography at the end” of The Barbary Coast, too. He prefaces the bibliography by saying that “[a] great deal of the material in this book comes from old-time San Franciscans and has never before been published.” He goes on to say that the list that follows are those of the “[s]everal hundred books and other published sources…consulted” that “were especially helpful.”

Front cover of Albert Dressler’s self-published 1927 booklet, Emperor Norton: Life and Experiences of a Notable Character in San Francisco.

The list includes newspapers. It also includes Benjamin E. Lloyd’s 1876 book Lights and Shades in San Francisco, which has a brief section about Emperor Norton.

But, the only “resource” on the list that is explicitly about the Emperor is Albert Dressler’s little booklet, Emperor Norton: Life and Experiences of a Notable Character in San Francisco, 1849–1880 — which Dressler self-published in 1927.

Lloyd describes the Emperor’s uniform — but says nothing about any “new” uniform or who might have provided it.

Dressler, however, does “ad-dress” the subject, writing of Emperor Norton that

His fancied import was sanctioned by the City, and the Board of Supervisors, amid fitting ceremony, voted him a new uniform at the expense of the City Treasurer when he began to look shabby.

This may be where the story of a City-supplied uniform for the Emperor got its start.

Asbury’s use of a phrase, “when his uniform began to look shabby,” that is so close to Dressler’s “when he began to look shabby” strongly suggests that Asbury just took the claim from Dressler then put his own paraphrase and embellishment on it.

This thing is, Dressler — writing nearly 50 years after the death of Emperor Norton — and as many as 60 or more years after what he claimed happened in the matter of the Emperor’s uniform — provided no more documentation for the claim than Asbury did. Which is to say: none.

Which begs the question: Is there documentation to be found?

Local newspapers did take note when Emperor Norton added a new accoutrement, such as his epaulettes or a different walking stick or hat, to his regalia — or when he appeared in altogether “new” uniform, as the San Francisco Sunday Mercury reported in July 1863:

Although “cap-a-pie” means “head to toe,” the Mercury doesn’t specify whether “new” meant brand-new or just different than before — or where the uniform came from.

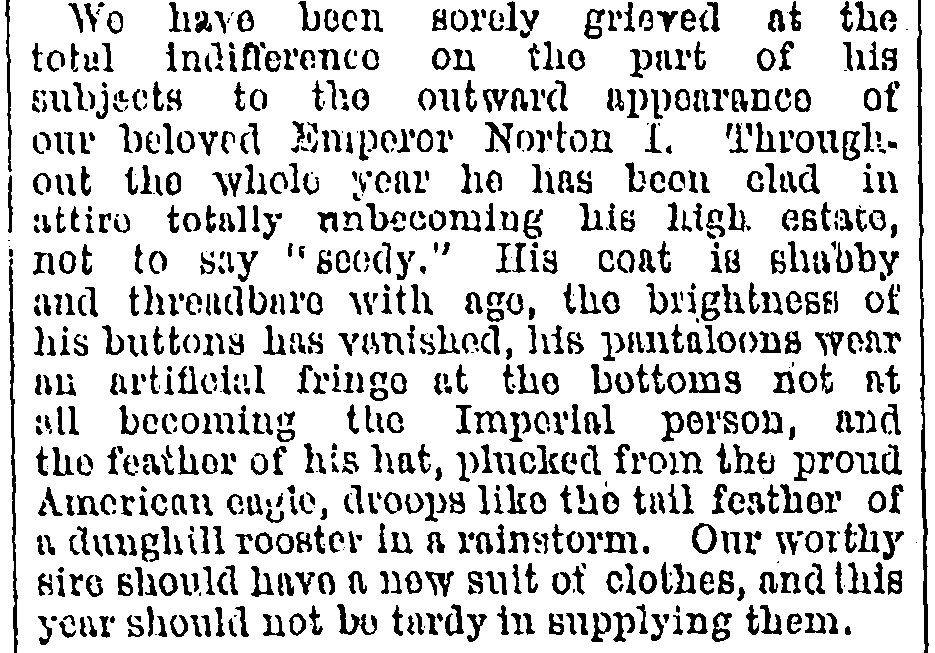

Less than two months earlier, in May 1863, the same paper had editorialized that

His Excellency is evidently growing careless of his personal appearance. The old blue coat and pantatoons, daubed over with stray brass buttons, and crowned with a pair of immense brass epauletts, is growing very seedy, greasy, and dilapidated. His military cap is slouchy, and gives sad token it may have been used for other purposes since the rise in cotton goods.

So, it’s possible that the July 1863 item is a satire “cap-a-pie.” Charming poem, though!

Whatever the Emperor was wearing in 1863, by 1865 he was sufficiently concerned about the state of his uniform to petition the Board of Supervisors for a remedy:

Note that the Emperor doesn’t request an appropriation but asks, more modestly, that the Supervisors issue “a Resolution ordering that tailors be a little more attentive.” Whether tailors had been “more attentive” before is unknown.

In any case, the Supervisors placed the request “on file,” i.e., they took no action.

In May 1868, Emperor Norton was back with a new, more elaborate petition to the Board of Supervisors. As reported in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, the Emperor had three requests, including that — the Bulletin’s words — the Board “designate a paper which shall be known as the Imperial Gazette” and that the Board “take measures to compel the Supreme of the United States to regard his solemn decrees and make his laws their guide in all future decisions.”

But, the first request was concerning his uniform:

“An Imperial Suppliant,” San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin, 7 May 1868, p. 3. Source: Genealogy Bank

That petition first sets forth that his Majesty’s robes are worn threadbare — so threadbare and shabby that the ignorant and unthinking crowd are forgetting the innate dignity of his person. His very government may be brought into contempt because his epaulettes are tarnished, the gay colors of his coat faded, the crested buttons lost and the embroidery torn. Nay, more, his Majesty’s full-dress never-mention-ems have lost their seat, and the Imperial limbs are cased in a pair of civilian’s bags.

There’s that word again: shabby — possibly where Albert Dressler got it.

A small digression: “Never-mention-ems” is a euphemism for “trousers.” The term, which dates to 1856, comes up in this wonderful 2009 post about the upcoming publication of the Historical Thesaurus of the Oxford English Dictionary. The writer uses “trousers” as the example word for how the thesaurus demonstrates the evolution of synonyms and related words. In the thesaurus, a note on the 1833 word “unimaginables” notes:

This 19th Century word, and others like “unwhisperables” and “never-mention-ems”, reflect Victorian prudery. Back then, even trousers were considered risque, which is why there were so many synonyms. People didn’t want to confront the brutal idea, so found jocular alternatives. In the same way the word death is avoided with phrases like “pass away” and “pushing up daisies.”

It appears that the Supervisors did not respond to any of the Emperor’s three requests — including the one about his uniform, if the following editorial item that the San Francisco Chronicle ran on New Year’s Day 1869 is any indication:

On the other end of 1869, the Chronicle published the following, which almost certainly is a hoax, given that J.J. McBride a.k.a. the King of Pain was a snake oil salesman who had a hard enough time keeping clothes on his own back, let alone having a suit to spare for Emperor Norton.

Certainly, the Emperor Norton would not have recognized the King of Pain as “His Majesty.”

It appears that in June 1872 the Emperor tried a different tack by appealing to the Mayor:

“The communication was laid on the floor in fragments.”

Some six weeks later the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Emperor Norton had “a new blue coat, with huge brass buttons” — but made no mention of where the coat came from. The line about diamond mines may have been the “wink” signaling that the whole item was a joke.

:: :: ::

FOR ALL OF this “absence of evidence” and “evidence of absence”…

It is the “court biographies” — the passages and articles and books and “books” of Messrs. Cowan (1923), Dressler (1927), Asbury (1933), Ryder (1939), Lane (1939) and Drury (1986) — that have proven most influential in shaping and codifying public opinion about what Emperor Norton said or didn’t say — did or didn’t do — had, or didn’t have, said or done to — or for — him.

I say “opinion,” because so often these “biographies” make claims that they don’t even try to document.

These claims include the one that the San Francisco Supervisors bought Emperor Norton a uniform.

In his 1986 biography Norton I: Emperor of the United States, William Drury acknowledges a number of fake decrees on this issue. But, in the end, he just asserts that the Board of Supervisors

voted to buy [Emperor Norton] new regimentals out of municipal funds. They bought the Emperor a new uniform and a beautiful new hat, a white beaver adorned with peacock plumes…”

That’s a lot of detail to provide, with no documentation. But, Drury leaves his readers wanting. Apparently, he just wants it to be true.

Drury’s predecessor Allen Stanley Lane is more circumspect. In his 1939 biography Emperor Norton: The Mad Monarch of America, Lane has a whole chapter titled “My Kingdom for a Suit.” After — all too credulously — cycling through a longlist of silly fake “decrees” on the subject, Lane comes to the Emperor’s 1872 letter to Mayor Alvord, then concludes:

The absence of further documents among the Norton papers on the clothes question warrants the conclusion that, officially or privately, His Majesty’s wardrobe was kept thereafter in a satisfactory condition.

Like Drury, Lane just wants it to be true. He doesn’t declare it outright like Drury does. But, in the “absence of evidence,” he sees an opening for the possibility that the Board of Supervisors stepped in to take care of Emperor Norton’s uniform and invites his readers to draw that conclusion.

This is like those who insist that, because it hasn’t been proven that Emperor Norton did not issue an anti-”Frisco” proclamation, they are justified in asserting that he did, even though there’s no documentation to support the claim.

But, that’s not how history works. Ultimately, the evidence must rule.

A significant body of documentary resources from the period of Emperor Norton’s reign, 1859–1880, has been digitized.

For example: Between them, the three historical newspaper databases that I consult most often — the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Genealogy Bank and Newspapers.com — include nearly every major and minor newspaper published in San Francisco and elsewhere in California during this period.

I performed 16 individual searches in each of these three databases — so, nearly 50 searches in all — combining the terms “Emperor Norton” (or “Norton I”) and “Board of Supervisors” with the terms “uniform,” “regalia,” “regimentals,” “suit,” “coat,” “clothes,” “clothing” and “wardrobe.”

I didn’t find a single result showing a newspaper report that the San Francisco Board of Supervisors had taken any action relative to Emperor Norton’s clothes — up to and including appropriating public funds for a new uniform.

Another example: The Internet Archive includes a large set of digital copies of the Board of Supervisors’ annual San Francisco Municipal Reports. This is the official compendium that — important for our purposes — includes detailed proceedings of the Board and the City Treasurer’s report.

The Archive includes the Municipal Reports for every fiscal year of the Emperor’s reign except 1860–61.

In each of these volumes, I performed a search on the terms “Emperor Norton,” “Norton I,” “Joshua A. Norton,” “Joshua Norton” and “Norton.”

The only reference to Emperor Norton in the Municipal Reports is in the volume for 1879–1880, which includes lists of his personal effects that were received by the Coroner at the Emperor’s death — and those that, by Resolution of the Board of Supervisors, subsequently were conveyed to the Society of California Pioneers.

:: :: ::

TWO CONCLUSIONS to be drawn from all this:

(1) Emperor Norton’s uniforms always were as they appear in the extant photographs of him: secondhand, cast-off military coats, often paired with mismatched trousers — “a pair of civilian’s bags” as the Bulletin put it.

(2) As with many of his other basic necessities, the Emperor’s sartorial needs were met through the kindnesses of individual friends and supporters — not by government beneficence.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...