Joshua Norton's First Public Moves in San Francisco Appear to Support His Claim of a November 1849 Arrival

Arrival Claim Originates With Norton But Never Has Been Independently Documented

New Discoveries That Appear to Support the Claim: Norton’s Possible Signature on a February 1850 Open Letter — and, in May 1850, a Temporary Business Address at an Auction House Whose Partners Also Signed the Letter

Earliest San Francisco Newspaper Reference to Norton

:: :: ::

This is part of our occasional series of Open Questions articles. These articles take "deep dives" into some of the most oft-repeated — but under-analyzed — historical claims about Joshua Norton / Emperor Norton. They offer source material for future exploration of questions that generally are presented as settled — but aren't.

:: :: ::

ON 29 MAY 1850, the following ad for Joshua Norton & Co. appeared on page 2 of the San Francisco Daily Pacific News:

Ad for Joshua Norton & Co. at 242 Montgomery Street, San Francisco, Daily Pacific News, 29 May 1850, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

The address, 242 Montgomery Street, was for an adobe cottage at the northeast corner of Montgomery and Jackson Streets that was owned by James Lick (1796–1876).

Both of Emperor Norton’s primary 20th-century biographers — Allen Stanley Lane in 1939 and William Drury in 1986 — cite Lick’s adobe at 242 Montgomery as Joshua Norton’s first business address in San Francisco.

But…

The same San Francisco newspaper that carried Joshua’s ad for 242 Montgomery provides evidence of a slightly earlier touch-down at a different address.

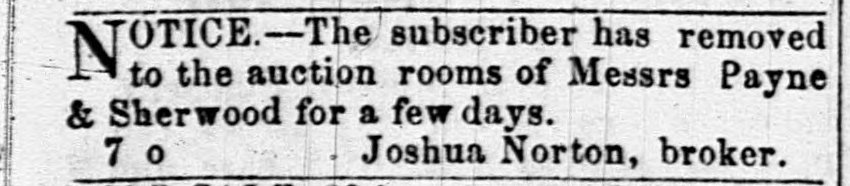

The 6 May 1850 issue of the Daily Pacific News includes the following notice that Joshua Norton has “removed to the auction rooms of Messrs Payne & Sherwood for a few days.”

Was Joshua doing a freelance gig at the auction house, or just renting a desk? Could be either.

Joshua Norton’s ad giving notice that the Payne & Sherwood auction rooms would be his business whereabouts “for a few days,” Daily Pacific News, 6 May 1850, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

During this period, “removed to” — meaning “moved to” — is a phrase that usually was seen in the context of newspaper ads announcing business relocations. Which is to say: “Removed to” always implied that the advertiser had “removed from” somewhere else.

Alas, if Joshua’s previous business address is in the scanned California newspapers of 1849 or 1850, the OCR* texts generated in the scanning of these editions did not translate well enough to return an earlier search result for “Joshua Norton.”

Put another way: The early May 1850 ad is the earliest reference to “Joshua Norton” in any of the major public databases of historical California newspapers — and points to what now has to be regarded as Joshua's earliest known San Francisco business address (see the following section for the address itself).

What does seem likely is that the occasion for Joshua’s having to “remove to” a different business address was the second great fire of San Francisco — which took place a couple of days earlier, on 4 May 1850.

A final detail worth noting about Joshua’s notice of 6 May 1850: He signs himself “Joshua Norton, broker.”

By the time, three weeks later, that Joshua announces himself doing business at 242 Montgomery, he is styling his enterprise “Joshua Norton & Co.,” a self-designation that disappears after April 1853 — both a casualty of Joshua’s changing fortunes and an acknowledgment of the reality he had been deserted by his former partner and now was going it alone.

:: :: ::

SO, WHO — and where — was Payne & Sherwood?

The earliest extant ad for the auction business of Theodore Payne and William J. Sherwood — published in December 1849 — finds Payne & Sherwood at the corner of Montgomery and Jackson Streets — the same intersection where Joshua Norton eventually landed:

Ad for Payne & Sherwood auctioneers, Daily Alta California, 14 December 1849. p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

As it happens, Payne & Sherwood was at 247 Montgomery — on the northwest corner of Montgomery and Jackson, and across the street from James Lick’s adobe at 242.

Here’s Payne & Sherwood’s listing in Charles P. Kimball’s San Francisco directory of 1850:

Listing for Payne & Sherwood auctioneers and commission merchants, Kimball’s San Francisco City Directory, 1850, p. 87. Collection of the San Francisco Public Library. Source: Internet Archive

And a detail from the firm’s newspaper advertisement of 30 April 1850 — the week before Joshua’s notice that this is where he would be found “for a few days.”

Detail from ad for Payne & Sherwood, Daily Pacific News, 30 April 1850, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Perhaps it was while here that Joshua learned of the vacancy at 242 Montgomery.

:: :: ::

EARLIER, we saw that — at least, at first pass — the first mention of “Joshua Norton” in a San Francisco newspaper appears to have been in May 1850.

But, the conventional wisdom has Joshua arriving in San Francisco in early November 1849.

How does one explain a 6-month delay between Joshua’s arrival and his appearance in the papers? Didn’t he need to get down to business?

Here are three speculative swings at an answer. Think of them as hypotheses in search of a theory:

1

JOSHUA ARRIVED WITH CASH AND COULD AFFORD TO FLOAT HIMSELF.

There is a legend of a $40,000 inheritance. This is undocumented.

But, whatever financial resources Joshua Norton brought with him…

Passage to San Francisco in the late 1840s and early 1850s was hard — whether by land or, as Joshua came, be sea.

And, for most anyone who arrived in San Francisco in 1849 or 1850, staying in San Francisco was a risky, sink-or-swim proposition.

Joshua Norton did not arrive wealthy like the McAllisters — he was a striver.

But, there were few, including Joshua, who upon arriving in San Francisco could afford to remain idle for long — certainly, not for six months.

2

JOSHUA WAS NOT YET ON HIS OWN — BUT WAS WORKING ANONYMOUSLY FOR SOMEONE ELSE.

This, too, seems to not be entirely true. Here’s why:

It turns out that there occasionally were newspaper ads for Joshua Norton in which his name was misspelled as “Joshua Morton” — with “M. Here’s one from July 1850, shortly after Joshua moved his business to 242 Montgomery:

Ad for Joshua Norton & Co. misspelled as “Morton,” Daily Alta California, 3 July 1850, p. 2. Source: California Daily Newspaper Collection

The typo itself is not surprising — but, “Morton” for “Norton” is not something I previously have focused on as a potential clue to Joshua Norton’s activities.

On 14 February 1850 — three months before Joshua’s early May 1850 ad — the Daily Alta published following open letter to San Francisco’s elected leadership, complaining about the disrepair of a certain section of Montgomery Street. The letter was signed by 31 firms and individuals doing business on Montgomery (or adjacent).

One of the signatories — bottom of the left column — is “Joshua Morton.”

Open letter “To the Common Council of the City of San Francisco,” signed by “Joshua Morton,” Daily Alta California, 14 February 1850, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Is this our Joshua?

There is a “Joshua Morton” that first appears in James B. Parker’s San Francisco Directory for the Year 1852–53, published in late 1852. And, it so happens that this Joshua Morton is listed as a commercial merchant (“com mer”).

But, this is more than 2½ years after the February 1850 letter. And, Joshua Morton is listed with his business at 68 California Street, between Front and Battery — more than two blocks east of Montgomery, the focus of the letter.

Meanwhile, the presence of Joshua Norton’s apparent friends at Payne & Sherwood on the list of signatories — together with the appearance of both Joshua and Payne & Sherwood (a) in Kimball’s San Francisco directory of 1850 and (b) in San Francisco newspaper ads that year — suggest that this is indeed our Joshua.

If so, this would put Joshua Norton in San Francisco by February 1850. It doesn’t tell us what Joshua was doing — or where he was doing it. But…

It would seem to close the gap between Joshua’s arrival in San Francisco and his appearance as a member of the local business community.

It would suggest that Joshua was on the scene and doing business in San Francisco for a few months before publishing notice of his “removal” to a new business location in early May 1850.

And, it would make this letter the earliest known newspaper reference to Joshua Norton in San Francisco.

3

JOSHUA ARRIVED IN SAN FRANCISCO LATER THAN NOVEMBER 1849.

This has to be admitted as a possibility, if only because independent documentation — such as a ship’s passenger list or some other contemporaneous news report — has not surfaced to substantiate Joshua’s own claim of a November 1849 arrival.

In fact, it appears that the story of Joshua Norton’s arrival in San Francisco originates with Joshua himself. (Note: Much of what follows summarizes a deep-dive on this issue that I published in February 2017.)

In November 1879, Emperor Norton told a San Francisco Chronicle reporter that he arrived on a ship from Rio de Janeiro via Valparaiso on 5 November 1849.

A few weeks later, in its 11 January 1880 article (“Le Roi Est Mort”) about the Emperor’s funeral and burial, the Chronicle reported that the same arrival story was “furnished by a citizen” who, like the Chronicle reporter, had heard it from the Emperor himself.

It appears that this “citizen” was Theodor Kirchhoff (1828–1899), a German poet, essayist, and memoirist who arrived in San Francisco in 1869 and befriended the Emperor shortly thereafter. Kirchhoff wound up penning two German-language pieces about the Emperor: a brief item in 1869 and a longer, more thorough article in 1886.

In the January 1880 correspondence with the Chronicle that I’m hypothesizing, Kirchhoff added the previously unreported detail that Joshua Norton arrived aboard the ship “Franzika” — something that Kirchhoff repeated in his 1886 article about Emperor Norton.

There were two ships from Rio that landed in San Francisco in November 1849 — but none on the 5th. The Franzeska landed on the 23rd.

All of Emperor Norton’s major and minor 20th-century biographers (a term one often has to use advisedly) — Robert Ernest Cowan in 1923; Albert Dressler in 1927; Allen Stanley Lane and David Warren Ryder in 1939; William Drury in 1986 — go with (a) Norton’s claim to have arrived in San Francisco in November 1849 on a ship from Rio, and with (b) Theodor Kirchhoff’s claim, after Norton’s death, that the ship was the Franzeska. But, none of these writers troubles himself to explain why his readers should accept this narrative, given that there’s no independent documentation of it.

If Joshua did not arrive on the Franzeska, it’s not difficult to see how he — or even Kirchhoff — could have seen a myth-making opportunity in forging a connection to the Franzeska, a name that so strongly evokes “Francisco.”

It appears that the first mention of a November 1849 arrival date for Joshua Norton is courtesy of Norton’s listing in Samuel Colville’s San Francisco Directory of 1856.

Listing for Joshua Norton, Colville’s San Francisco Directory, 1856, p. 162. Collection of the San Francisco Public Library. Source: Internet Archive

Colville published his directory in October 1856 — just two months after Joshua was forced to declare bankruptcy.

Having lost his previous business addresses to foreclosure, Joshua was using — as his business address — Pioneer Hall, the Society of California Pioneers clubhouse on Portsmouth Square.

There’s no record that Joshua ever was a member of the Pioneers. If he had been a member, he would have been required to validate that he arrived in California prior to 1850.

So, if Joshua did not arrive in California prior to 1850, he would have had special incentive to give the impression that he did — if he was using the Pioneers’ address.

At the same time: If the Pioneers simply respected Joshua as an early San Franciscan and were providing him with the courtesy of using their address on that basis — rather than as a potential or prospective member — they might not have looked too closely into whether he actually arrived before 1850 or, for example, arrived on one of the slightly later ships from Rio that landed in San Francisco in January, February, or April of 1850.

None of this is to say that Joshua Norton did NOT — as he claimed — arrive in San Francisco in November 1849 on a ship from Rio — just that there is not yet any independent evidence to substantiate that.

Anyone looking for the earliest public record of Joshua Norton in San Francisco would be on better footing with the theory than the “Joshua Morton” listed as a signatory on the open letter of February 1850 is in fact Joshua Norton.

Assuming that Joshua arrived in San Francisco no later than November 1849, his signature on that letter would narrow the gap between his arrival and his newspaper “debut” to 12 weeks or less — rather than 6 months.

Indeed, 12 weeks might have been about how much time Joshua would have needed to find a place to live; get settled; and become sufficiently established and known in business circles to be invited to sign a letter to City elders in the first place.

If it was Joshua Norton — not Morton — who signed the letter of February 1850 letter, that would bolster the circumstantial case for November 1849 as the date of Joshua’s arrival in San Francisco.

* Optical character recognition

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...