The Ubiquitous But Enigmatic Life of An Early Engraving of Emperor Norton

Across a 9-Year Run and Two Different Printers, An Uncredited Cameo of the Emperor on His Promissory Notes Was Inked Thousands of Times

SURELY no single artistic depiction of Emperor Norton has been reproduced more times, over a longer period, than the “cut” of the Emperor that featured on the fronts of his promissory notes.

Numismatic scholars estimate that, in total, more than 3,000 of these notes were printed. Nearly all of them — including all of those signed and dated between January 1871 and the Emperor’s death in January 1880 — featured the same engraving of him.

The two note printers of record are Cuddy & Hughes, who printed the extant notes Emperor Norton signed and dated between November 1870 and August 1877, and Charles A. Murdock & Co, who printed those signed and dated between January 1878 and January 1880.

Following is a view of a 5-dollar note by Cuddy & Hughes that Emperor Norton signed and dated on 25 January 1871. This note, in the California Historical Society Collection at Stanford, appears to be the earliest known example that features the engraving of the Emperor. Alas, the Trust does not have a scan of this particular note, and the image of it that currently is online nearly 20 years old and of 20-year-old size (small) and quality (poor) . Shown here is the note exhibited at our bicentennial talk/exhibit Will the Real Emperor Norton Please Stand Up? held at the California Historical Society on 1 February 2018:

Emperor Norton promissory note, 5 dollars, signed and dated 25 January 1871. Printed by Cuddy & Hughes. California Historical Society Collection at Stanford. Shown here as exhibited at The Emperor Norton Trust’s bicentennial talk/exhibit Will the Real Emperor Norton Please Stand Up? held at the California Historical Society on 1 February 2018. Detail from photograph by John Lumea.

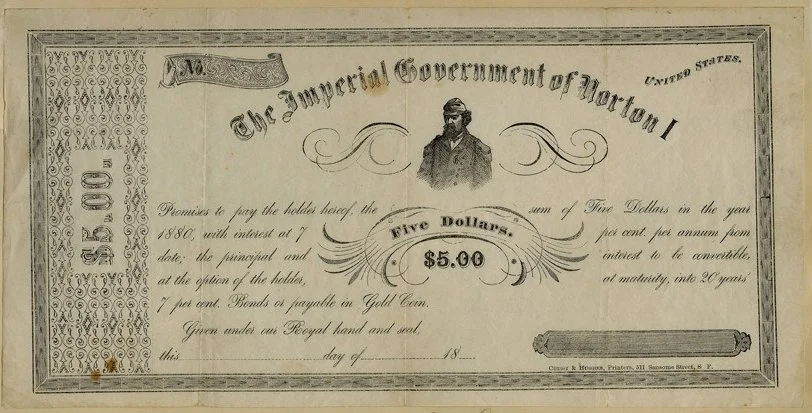

The following unsigned and undated remainder of the same Cuddy & Hughes note shows a much clearer view of the engraving of the Emperor. Oddly, the “I” following “Norton” in the curving title above the engraving is not in the same ornate font as the rest of the title. Was the printer lacking a capital “I” in that font, having already used one in the word “Imperial”? Towards the bottom right-hand corner — between the border and the signature field — the imprint “Cuddy & Hughes, Printers, 511 Sansome Street, S.F.” suggests no particular relationship between the firm and the Emperor:

Emperor Norton promissory note, 5 dollars, unsigned and undated remainder. Printed by Cuddy & Hughes. Source: PMG

Here’s a Cuddy & Hughes example from later in the same year — signed 17 August 1871. Note that the Cuddy & Hughes imprint — centered along the bottom edge, below the border — now identifies the firm as “Printers to His Majesty Norton I”:

Although there are Cuddy & Hughes-imprinted notes as late as August 1877, John Cuddy and Edward Hughes dissolved their partnership in July 1876. This suggests that Emperor Norton must have had a stock of blanks that he continued to use until they ran out.

Here’s a relatively late Cuddy & Hughes note — again, with the engraving of the Emperor — signed 14 July 1876:

Emperor Norton promissory note, 50 cents, serial number 1994, signed and dated 14 July 1876. Printed by Cuddy & Hughes. Source: Heritage Auctions

During this period, Emperor Norton and the printer Charles Murdock befriended one another at the First Unitarian Church. It appears that, at some point in late 1877, the Emperor engaged Murdock as the next printer of his notes.

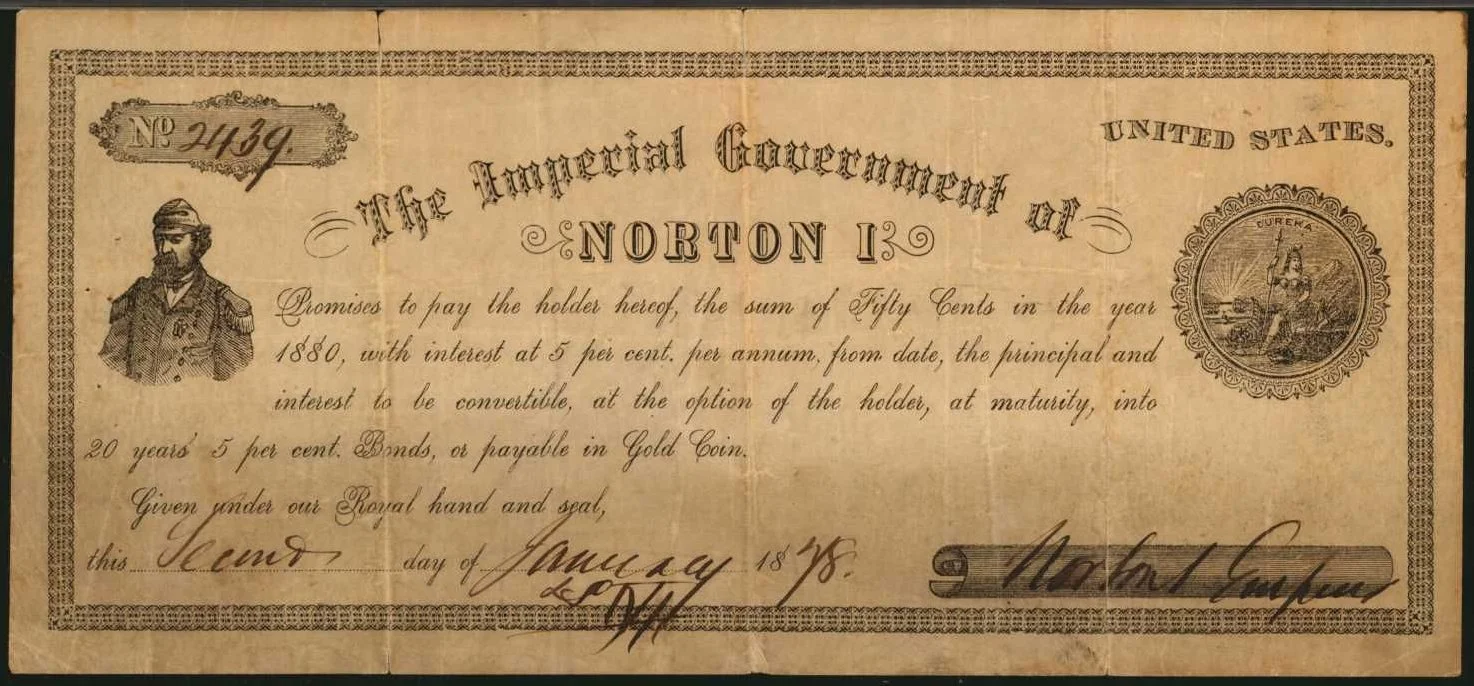

Here is one of the earliest notes that Charles Murdock & Co. printed for the Emperor — signed and dated 2 January 1878. Note the engraving of the Emp:

Emperor Norton promissory note, 50 cents, serial number 2439, signed and dated 2 January 1878. Printed by Charles Murdock & Co. Source: Stack’s Bowers

And here is one of the last Charles Murdock & Co. notes that Emperor Norton signed. It is dated 19 December 1879 — just three weeks before the Emperor’s death:

Emperor Norton promissory note, 50 cents, serial number 3005, signed and dated 19 December 1879. Printed by Charles Murdock & Co. Source: Heritage Auctions

:: :: ::

COMES a number of questions:

When was the engraving of Emperor Norton created? By — or for — whom?

How did Charles Murdock come by the original cut to use for his notes for the Emperor — after Cuddy & Hughes stopped using it for theirs?

What happened to the cut after the Emperor’s death — and did it ever find other uses?

The “origin questions” are the only ones it is possible to address with a relative degree of certainty. The rest is speculation.

Perhaps the most important circumstantial evidence in dating the engraving is the fact that the earliest Cuddy & Hughes notes did not feature a depiction of the Emperor.

Here’s the earliest-extant Cuddy & Hughes note — signed and dated 11 November 1870:

Of interest: The imprint on this note — centered along the bottom edge, below the border — has Cuddy & Hughes as “Printers for his Majesty Norton I,” with the “h” of “his” in lower case.

So, over the course of as little as 9 months, the Cuddy imprint shifted from “Printers for his Majesty” by November 1870 — to the pedestrian “Printers” by January 1871 — to “Printers to His Majesty” by August 1871.

This suggests that there was a lengthy deliberation between the partners in Cuddy & Hughes, John and Edward, about whether — and how — to publicly express their relationship to Emperor Norton. It seems the partners may have concluded that their original [?] “Printers for” was a little strong — suggesting either that the Emperor was paying for printing of the notes (he wasn’t) and/or that their own posture towards the Emperor was subservient or dependent (it wasn’t at all). Perhaps John and Edward decided that “Printers to” struck just the right…note — not least, because associating with Emperor Norton in some way was good for business.

The figure on the left is Columbia. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Columbia — which previously had been used as a symbol for the Americas and the “New World” — was taken up and forged as the female personification of the United States in particular, lending its name to Columbia University and the District of Columbia (among many other places), as well as patriotic hymns and songs like “Hail, Columbia” and “Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean.”

By the early 20th century, the Statue of Liberty had supplanted Columbia as the female symbol of the United States — although Lady Liberty also was seen as incorporating and reimagining Columbia into something new.

There is plenty of space on this note for Emperor Norton to have affixed his red wax “N1” seal without obscuring Columbia. The Emperor’s placement of his seal directly on Columbia’s head could be read as a potent symbol of his own intentions.

Detail of Emperor Norton promissory note, 50 cents, signed and dated 11 November 1870, showing Emperor’s red wax “N1” seal. Detail rotated 180 degrees to show accurate orientation, with a 5-pointed crown above the “N” and crossed swords in the ring below the “1.” Note printed by Cuddy & Hughes. Collection of the California State Library.

Presumably, if there had been a readily available and fit-for-purpose original portrait engraving of Emperor Norton when Cuddy & Hughes designed and printed the batch of notes that included the November 1870-dated note above, the Emperor could have told Cuddy & Hughes where to find it.

The absence of a Norton cameo on the November 1870 note and the presence of one by late January 1871 suggests that Cuddy & Hughes had a cut of the Emperor purpose-made sometime between November 1870 and January 1871.

During this period, engraving was its own artistic and commercial discipline. But, it does not appear that Cuddy & Hughes ever marketed engraving services. San Francisco directories of the period do not show any engravers in the firm’s employ — and the obituaries for John Cuddy and Edward Hughes do not mention artistic engraving in the resumé of either man.

Rather, Cuddy & Hughes described itself — and was reputed as — as a “book and jobs printer.” Its expertise was in the design, layout, and printing of pages for everything from bill-heads, flyers, and posters to books. Notably, the firm printed the weekly Pacific Appeal newspaper, which published Emperor Norton’s proclamations between September 1870 and May 1875.

But, the firm did its work using a toolbox of type, design elements (borders, etc.), and artwork created and fabricated by others. This included the cameo of Emperor Norton. Most likely, Cuddy & Hughes commissioned this from an outside artist.

Pretty clearly, the artist modeled the engraving of the Emperor on an 1867 photograph of the Emperor by Bradley & Rulofson:

:: :: ::

SO HOW did this original engraving make its way from Cuddy & Hughes to Charles Murdock & Co.?

As we noted, John Cuddy and Edward Hughes dissolved their partnership in July 1876. But, a year earlier, in May 1875, real estate speculator Charles R. Peters had sued Peter Anderson, the editor and publisher of the Pacific Appeal, in retaliation for the Appeal’s publication of an unsigned anti-Peters proclamation attributed to Emperor Norton.

Peters dropped the suit — but, in order to effect this, Anderson disinvited and barred the Emperor from bringing the Appeal any more Proclamations to publish.

Given that the Appeal probably was Cuddy & Hughes’ leading client — i.e., its bread and butter — it seems unlikely that the firm would have printed any more scrip for Emperor Norton after May 1875.

Before purchasing the printing establishment that became Cuddy & Hughes in 1869, John Cuddy had been admitted to the bar in both New York and California. After selling his interest in the firm to Edward Hughes, Cuddy returned to the practice of law. (In fact, Cuddy’s law office between 1876 and 1878 was 636 Clay Street — just around the corner from the Emperor’s digs at 624 Commercial.)

Edward Hughes continued to run the printing firm and to print the Pacific Appeal, initially under his own name, then — after taking a business partner, Morris M. Grossman, in July 1877 — as the lead partner in Hughes & Grossman.

Would Edward Hughes have seen any reason to hold on to the cut of Emperor Norton that he and John Cuddy used to print notes for the Emperor between late 1870 and mid 1875? Probably not.

Two possible scenarios — either:

1

Cuddy & Hughes gave the cut to Emperor Norton in mid 1875 and the Emperor brought the cut to Charles Murdock in late 1877 — or…

2

Edward Hughes held on to the cut until Charles Murdock came to ask for it in late 1877.

:: :: ::

WITH CHARLES MURDOCK printing Emperor Norton scrip featuring the familiar Norton cameo until weeks, even days, before the Emperor’s death, there’s every reason to think that both Murdock and the Emperor believed the arrangement would continue indefinitely — and that Murdock had the Norton cut in his keep when the Emperor died.

Did Murdock ever find any future occasion to print the engraving of Emperor Norton that he had used to print the Emperor’s scrip between the end of 1877 and the beginning of 1870?

Did another printer ever come to Murdock requesting use of the cut for another project — perhaps a newspaper or magazine article?

Both are open questions — and we’ll keep our eyes open to these possibilities.

Charles Murdock wrote fondly of the Emperor in his memoir published in 1921.

It’s pleasant to imagine that Murdock still had the old cut when he died in 1928.

Where the cut is now is anybody’s guess.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...