News of Emperor Norton Reaches Russia-Owned Alaska in 1866

WELL, not exactly “news” — as we’ll see.

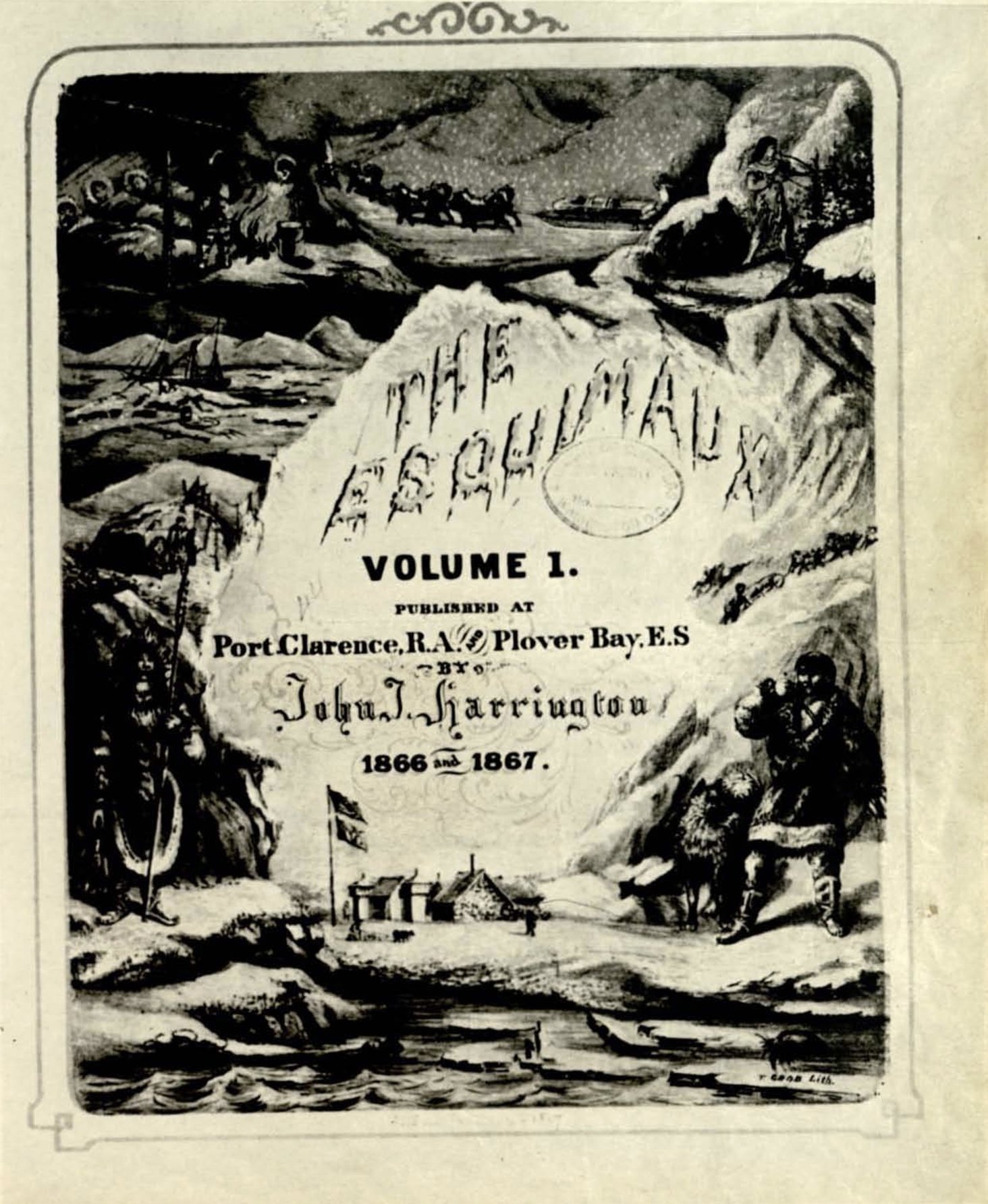

The period from October 1866 to September 1867 saw the publication, in manuscript form, of a monthly journal called The Esquimaux. There were twelve issues — the first ten published from Port Clarence, R.A. (Russian America), the last two from Plover Bay. N.E.S. (North East Siberia).

The editor and proprietor of The Esquimaux was John J. Harrington. In October 1867, Harrington had the complete run of the journal elegantly printed in San Francisco — as a kind of memorial edition.

Here’s the title page of the print edition. (The credit at bottom righthand corner appears to read “T. Grob, Lith.” If so, this almost certainly is the same T[heodore?] Grob whose 1863 engraving of a public military exhibition (“sham fight” and drill) in Oakland features one of the earliest artistic depictions of Emperor Norton. A hi-res image of the earlier work can be viewed on the Stanford University Archives page here.)

And here’s the masthead as it appears in this edition:

J.J. Harrington opens the print edition with a detailed historical note explaining the occasion for the journal.

In 1864–65, Harrington relates, Western Union began an active operation to connect North America and Asia by telegraph across the Bering Strait. The entity that laid the groundwork for the operation was known as the Russian–American Telegraph Company.

Work began in earnest in July 1865, when Charles S. Bulkley, the U.S. Army engineer who was running the project, brought an initial surveying party of 50 employees on two vessels from San Francisco to Sitka, R.A.

In mid 1866, after a year of exploration, the workforce was increased to 300 — with 40 of those being stationed at Port Clarence, R.A., under the command of Daniel B. Libby. It was in Libby’s honor that the outpost was designated Libbysville.

The following detail from an 1867 map shows Port Clarence and, immediately below it, “Depot of R.A. Tel. Comp.”, i.e., Libbysville. (It’s purely serendipitous that “Norton Sound” and “Norton B[ay]” are not far away. A number of other place names in the orbit of Port Clarence will ring a bell with those who know the Norton biography: “Good Hope B[ay]” brings to mind the Cape of Good Hope, in South Africa, where Joshua was raised and spent his early years, while “C[ape] Beaufort” recalls Beaufort Vale, where Joshua’s family spent their first year or two after arriving in South Africa.)

Detail of map, "North Western America Showing The Territory Ceded By Russia To The United States," 1867, by Charles Sumner (1811–1874). Source: David Rumsey Map Collection (full map)

Harrington writes:

Here, amid the Arctic snows, when daylight was only visible for an hour or two, and it was therefore almost impossible to prosecute our labors, to while away some tedious hours, this little paper was produced.

It seems that The Esquimaux was a hyperlocal project — produced by, and for, the tiny band of 40 Western Union employees living for a brief moment in Libbysville.

He continues:

At the earnest solicitation of many, who witnessed the inception, and close of the work, it is now presented in this form to the public. Pretending to no literary excellence, it is simply offered as a memorial, and to place upon record the first newspaper ever published in our new territory of Alaska.

The Alaska Purchase, establishing U.S. ownership of the Alaskan territory, took place in March 1867, with the transfer formalized six months later and the U.S. flag-raising solemnized on 18 October 1867 — a few weeks before the publication of Harrington’s print edition of The Eskimaux.

:: :: ::

IN HIS more general Preface to the 1867 print edition, J.J. Harrington writes that The Eskimaux [emphasis mine]

is a monthly journal, published in the ice-bound North among a party of whites, whose time, for the most part, was necessarily idle. There, shut out from the great civilized world, everybody looked to his neighbor, as a source of knowledge and amusement, and this was one of the means employed to make the hours pass swiftly by….

It seems clear that an item about Emperor Norton that appeared in the second issue, published on 4 November 1866, was meant to satisfy the need for amusement — not knowledge.

The item is teased in a group of subheads for a “Telegraphic” feature highlighting “The Latest Intelligence!” Fifth from the top: “Intended Marriage of Emperor Norton.”

Headlines for “Telegraphic” feature in The Esquimaux, V1N2, 4 November 1866. Source: Alaska State Library

The first three items leave no doubt that the “telegraphs” were composed by someone with their tongue planted deeply in their cheek:

First three items for “Telegraphic” feature in The Esquimaux, V1N2, 4 November 1866. Source: Alaska State Library

Here’s the “telegraph” about Emperor Norton:

Humorous item about Emperor Norton for “Telegraphic” feature in The Esquimaux, V1N2, 4 November 1866. Source: Alaska State Library

SAN FRANCISCO, Aug. 7th, 1866.

It is reported in official circles, that Emperor Norton I, has proposed to the Princess of Goat Island, and that their nuptials will shortly take place. The whole country is in an uproar in consequence of the coming event, and shop-keepers are importing dry goods, etc., for the blushing bride

:: :: ::

FOR THE RECORD, I find no other report — farcical or otherwise — in 1866 or otherwise — to connect Emperor Norton with any “Princess of Goat Island.”

Which invites the conclusion that this “telegraph” about the Emperor sprung from the fertile imagination of someone in Libbysville.

The survey crews shipped out from San Francisco — so it’s a good bet that some of the 40 who ended up in Libbysville had lived in San Francisco or at least knew the city well enough to know who Emperor Norton was.

The Western Union project struggled to overcome steep logistical hurdles. A rival project to lay a transatlantic telegraph cable connecting the United States and Europe fared better. Indeed, the completion of the transatlantic cable in 1866 led Western Union to cut its losses and abandon the Russia–America effort. In summer 1867, the survey crews at various locations around the Bering Strait — including Libbysville — were collected and brought to Plover Bay, on the Siberian side.

Daniel Libby himself was on the clipper Nightingale that returned to San Francisco from Plover Bay, as evidenced by his 8 October 1867 diary entry written aboard the Nightingale:

Excerpt of Daniel B. Libby diary aboard the clipper Nightingale with 8 October 1867 entry for arrival at San Francisco. Source: Alaska State Library

The San Francisco directory for 1867 shows a listing for Libby — and he is listed again in 1868, as “telegraph superintendent.” But, there are no listings for him in the years prior to the Western Union survey of 1866–67.

J.J. Harrington had a much better opportunity to have become acquainted with the Emperor before The Esquimaux debuted in late 1866.

Harrington first appears in the San Francisco directory of 1860, as an “apprentice” at the Daily Morning Call — and continues to be listed at the Call through the directory of 1865, when he joined the Western Union survey.

It appears that Harrington started in the Call’s print shop then moved to the business side.

On its face, it makes sense that someone who had spent five years learning the ropes at a major San Francisco daily would have the impulse to start his own paper.

Worth remarking: The San Francisco Chronicle and Examiner both took note, in December 1867, of Harrington’s print edition of The Esquimaux. But it appears that only in his old paper, the Call, did Harrington take out a November 1867 front-page ad promoting the upcoming publication of the work:

Indeed, it’s the Call that cracks a window on what really interests us here…

After a fire destroyed the Morning Call’s previous offices at the southeast corner of Montgomery and Clay Streets in November 1862, the Call in early 1863 moved to new digs at 612 Commercial Street between Montgomery and Kearny. (The Call building was in the area now occupied by the off-street entrance path to the San Francisco Historical Society / Museum of San Francisco, at 608 Commercial.)

Some 1½ to 2½ years later — between late summer 1864 and late summer 1865 — Emperor Norton moved just three doors up from the Call, to a third-floor room at the Eureka Lodgings, at 624 Commercial. (The Eureka building was on the site now occupied by a 4-story apartment building at 650–654 Commercial, adjacent to the west of Empire Park.)

This opens up the possibility of a window when Emperor Norton lived and J.J. Harrington worked in the 600 block of Commercial Street at the same time.

Even if Harrington and the Emperor did not meet — and the odds seem better than even that they did — Harrington during his five years at the Call must have spied the Emp with some regularity, whether on Commercial Street or elsewhere in the neighborhood that both men frequented.

Moreover: As an eyewitness to the earliest years of Emperor Norton’s reign — and as a member of the very institution, the Fourth Estate, that was most fascinated with the Emperor during this period — J.J. Harrington likely would have been steeped in local attitudes, reports, and gossip about the Emperor and surely would have cultivated his own view of the Emp.

All of this together makes for a good bet that the Esquimaux item about Emperor Norton’s fictionally impending nuptials was Harrington’s handiwork.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...