Notes on His Majesty's Printers

TO SPEAK OF "His Majesty's printer" is to speak of the printer of His Majesty's bonds. But we begin with his Proclamations.

On Saturday 7 January 1871, the Pacific Appeal, an African-American-owned and -operated abolitionist weekly in San Francisco, published the following on its front page:

Proclamation.

Being anxious to have a reliable weekly imperial organ, we, Norton I, Dei Gratia Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico, do hereby appoint the PACIFIC APPEAL our said organ, conditionally, that they are not traitors, and stand true to our colors.

NORTON I.

SAN FRANCISCO, Dec. 23, 1870.

The Emperor had grown weary of all the fake proclamations being published over his "signature" at the Daily Alta California and so many other Bay Area papers.

The Pacific Appeal's editor, Peter Anderson, continued to publish Emperor Norton on the paper's front page nearly every week until May 1875, when an item accusing Charles Peters, a real estate developer, of various deceptions made its way to the second page.

The item was written in the style of the Emperor but was of questionable authorship. Indeed, the Emperor had three signed Proclamations on the front page of the same issue. No matter. Peters threatened suit against the Appeal, and, if the suit was to be avoided, somebody had to pay. Anderson — or so it appears — made Emperor Norton the fall guy, publishing "A Retraction" that "forbid him hereafter bringing anything to our office for publication." And that was that.

In fact, in the few months before Emperor Norton made his relationship with the Pacific Appeal official — and starting at least as early as September 1870 — the Appeal had published several Emperor-attributed proclamations that appear to be anything but official. Which suggests that even the Appeal was not immune to the temptation of publishing prank decrees.

Norton's biographer, William Drury, explains that Peter "Anderson never saw his paper until it was published, but simply assembled the editorial matter and sent it out to be printed, trusting others to set the type and run the press. So that it was always possible for something to slip in that had never passed his desk."

:: :: ::

THERE IS, however, one of the "pre-official" proclamations that has a grain of truth and merits attention. And here we come to our subject.

Between July 1870 and May 1871, Europe was beset by the conflict known as the Franco-Prussian War. French and German emigrés who had been in San Francisco for years led charity efforts in support of their suffering countryfolk.

One of these efforts was a grand fair held in the Mechanics' Pavilion in late September 1870 to raise money for the French. Emperor Norton was in attendance on Saturday 24 September 1870 — and, in its review of the fair in the next day's paper, the San Francisco Chronicle sported itself a few snarky lines to remark on the fact (see under "The Auction," column 2, in the original article here):

Sale of goods commenced at half past eight o'clock, with unbounded enthusiasm. The prices realized were positively marvelous. Everything offered brought at least several times its value. Little trifles worth twenty-five or fifty cents commanded as many dollars....Emperor Norton I, San Francisco's privileged bummer, wishing to contribute his mite to the good cause, liberally donated his check on his private banker for $1,000,000. His High Mightiness confidently believed that it would sell for at least fifty millions of dollars; but his banker, like Tom Mooney, being non-come-at-able, the check had to submit to a serious shave, bringing the moderate sum of $30.

The following Saturday, on 1 October 1870, the Pacific Appeal ran two Norton proclamations — the first of which was a rebuttal and refutation of the Chronicle's insults [emphasis added]:

Statesmanship.

PROCLAMATION.

Whereas, The Chronicle of last Sunday in the course of noticing the events which took place on Saturday afternoon and evening at the French Fair, then being held at the Pavilion, to refer to us personally as "San Francisco's privileged bummer," and making false representations as to the value of our national scrip, thereby hoping to injure our person and prevent the sale of said scrip.

Now, therefore, we issue this decree to correct the erroneous impression which the Chronicle thereby sought to create. Our script sold for $150 premium, which the purchaser generously donated to the Fair, the par value of which has already been received by our bankers in Paris, so stated. As to the Chronicle calling us names, we would deem this attack too contemptible and beneath our notice, if it were not for the proscriptive policy of the press, with few honorable exceptions, which is undermining our government. The proprietors of the Chronicle should remember that "People who live in glass houses should not throw stones." During the whole course of our administration of the national affairs we never received the same treatment as they have at the hands of Messrs. Freidlander, Ralston and others.

The poetry in the Figaro last week, was a forgery.

NORTON I.

September 30th, 1870.

This may be the earliest published reference by Emperor Norton himself to the promissory notes that he began to sell during this period.

Two weeks earlier, in its issue of 17 September 1870 — eleven years, to the day, after Joshua Norton declared himself Emperor — the Appeal itself had weighed in on the enterprise with this tiny item on page 2, column 1:

UNREDEEMABLE bonds—Emperor Norton's.

CUDDY & HUGHES (1870-1877)

Why did the Appeal feel the need to editorialize about this?

Perhaps it was just a throwaway line — the latest in an endless parade of such lines trolled out by newspapers and magazines, at the Emperor's expense, to fill out a given edition's final column inches.

But, perhaps it also was offered for a more specific purpose: as a preemptive disclaimer against the appearance of any conflict of interest, given that the printer of the paper and the printer of the bonds were one and the same: the firm of John Cuddy (c.1844–1914) and Edward C. Hughes (c.1848–1912), operating professionally as Cuddy & Hughes.

In fact, Cuddy & Hughes and the Pacific Appeal occupied the same building — at 511 Sansome Street, on the southwest corner of Sansome and Merchant.

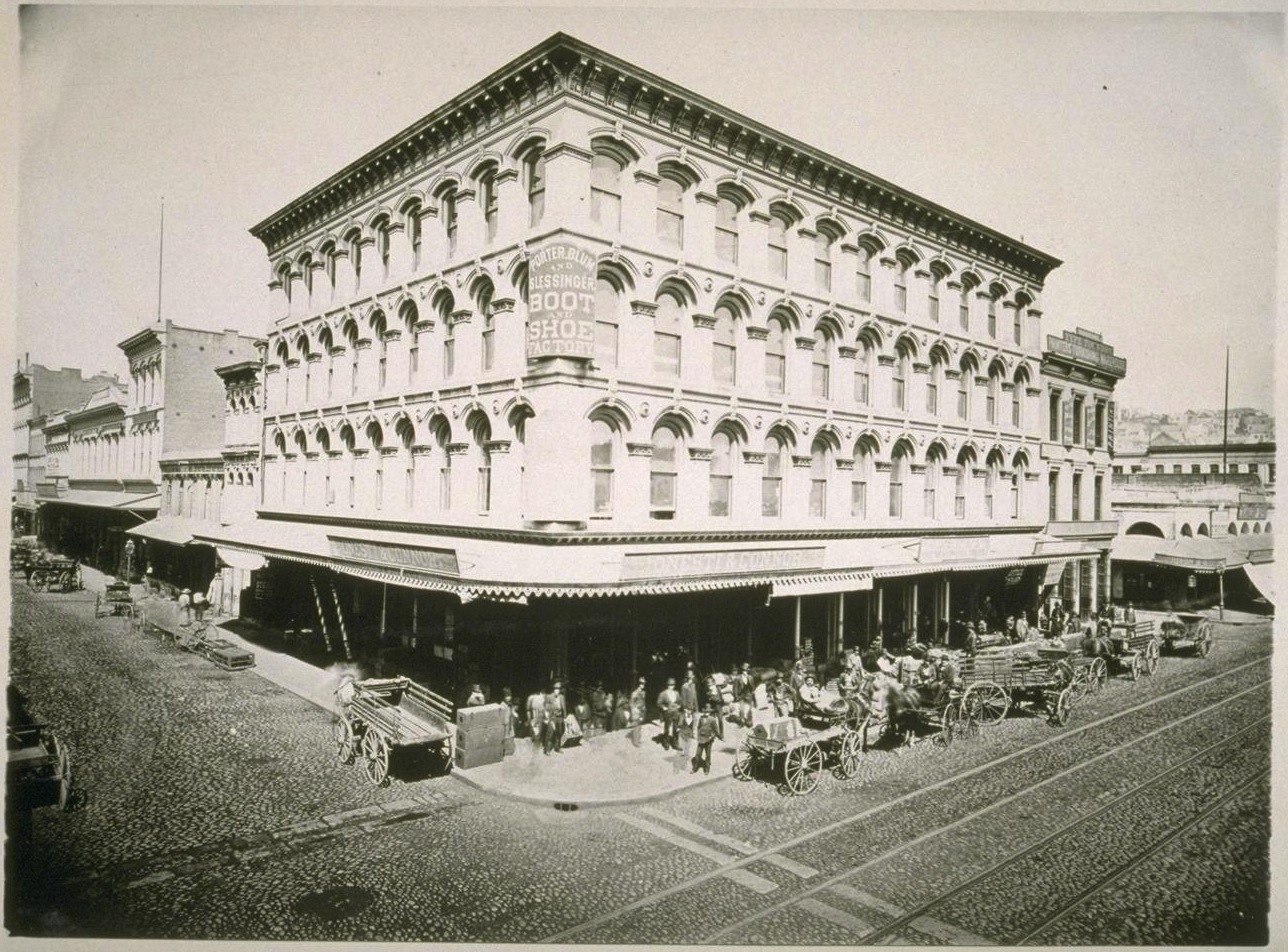

The building appears in the following rarely seen photograph of the second Niantic Hotel, on the northwest corner of Sansome and Clay Streets.

First, a little background: The ship Niantic — built in Connecticut in 1832; used for trade with China until 1840; then converted for use as a whaling ship for most of the 1840s — arrived in San Francisco on 5 July 1849, only to be quickly deserted by her crew.

The ship was sold; dragged out into the bay at high tide; then intentionally run aground near what is now the northwest corner of Sansome and Clay, where the ship's hull was roofed over and appropriated for various uses, including the original Niantic Hotel, warehouses, shops and offices.

The great fire of May 1851 burned the "ship" down to the waterline. But from the bones that remained arose a second Niantic Hotel, shown here. Sansome Street runs north-south in the foreground, with Clay Street headed west from the bottom left corner.

The San Francisco Public Library cites 1865 as the date of its own cropped version of this photograph.

The second Niantic Hotel, at the northwest corner of Sansome and Clay Streets, San Francisco; possibly dated 1865. Both the printing firm of Cuddy & Hughes and the Pacific Appeal newspaper operated out of the building visible at the far right: 511 Sansome, at the southwest corner of Sansome and Merchant. Photograph from the collection of James R. Smith. Scan provided courtesy of the owner. (A large detail from this photo appears in Smith's 2005 book, San Francisco's Lost Landmarks.)

What interests us is 511 Sansome — the tall 3-story building peeping in from the right side of the frame.

It was to this building that Thomas Agnew and Thomas Deffebach — known as "the two Toms" — had relocated their printing firm, Agnew & Deffebach, four years earlier, in 1861.

In April 1862, Peter Anderson started publishing the Pacific Appeal. The masthead listed the address of the paper as "No. 79 Merchant Street." There is a two-year gap in the record starting in September 1868; and, when it picks up again in September 1870, the masthead address has been changed to "S.W. corner of Merchant and Sansome Streets. But, a draft African American Citywide Historic Context Statement prepared for the City and County of San Francisco in 2016 under the direction of the San Francisco Planning Department suggests that "79 Merchant" was just a different address for the building at 511 Sansome (see page 31, here).

By 1867, Thomas Deffebach had bought out his partner's interest and the printing firm — still at 511 Sansome — was operating as T.B. Deffebach and Co. Agnew would remain an employee of the firm for nearly another decade.

Langley's city directory for 1868 directory shows a new listing for John Cuddy as "foreman at T.B. Deffebach & Co." And the 1869 directory reflects that Cuddy has taken on his new partner, Edward C. Hughes, and that the firm is operating as Cuddy & Hughes.

Three years later, in 1872, the second Niantic Hotel was demolished and replaced by a new Niantic Building, which occupied a larger site that stretched the full length of Sansome Street between Clay and Merchant — except for 511 Sansome, the building at the southwest corner of Sansome and Merchant, which remained the home of Cuddy & Hughes and the Pacific Appeal.

This undated and uncredited photograph of the building seems to make it clear that the building at the far right of the earlier photograph is 511 Sansome.

The Niantic Building (1872), at the northwest corner of Sansome (in the foreground) and Clay Streets, San Francisco. The building adjacent and to north, on Sansome, is 511 Sansome, at the southwest corner of Sansome and Merchant. Depending on when this photo was taken, Cuddy & Hughes and/or the Pacific Appeal newspaper may no longer have been operating out of the building. Photograph in the collection of the Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley. Source: Calisphere.

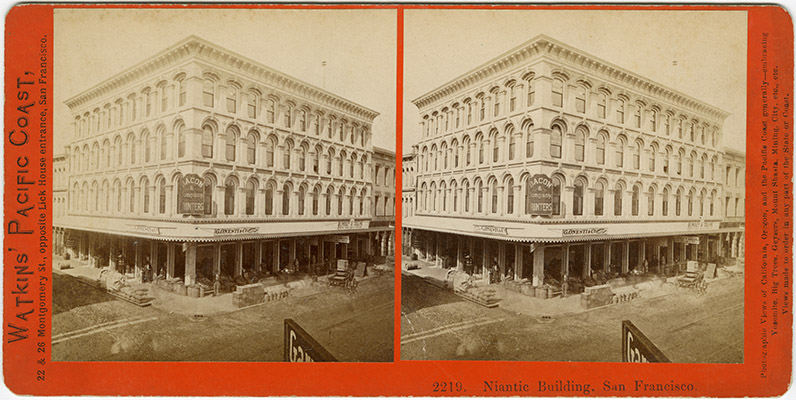

The photographer Carleton Watkins captured a similar view that shows a little less of 511 Sansome.

Stereograph of the Niantic Building (1872), San Francisco, by Carleton Watkins (1829–1916); possibly dated 1874. Source: San Francisco Public Library.

The San Francisco Public Library and other institutions that have this stereograph in their collections leave it undated. But the Library cites 1874 as the date of its cropped photographic print of the Watkins view.

:: :: ::

IN HIS BIOGRAPHY San Francisco Lithographer: African American Artist Grafton Tyler Brown (University of Oklahoma Press, 2014), the historian Robert J. Chandler surveys the San Francisco printing scene between 1865 and 1880 and asks [emphasis added]:

With sharp competition from 125 San Francisco printing and lithographic firms over fifteen years, how did a job printer stand out? In 1870, John Cuddy and Edward C. Hughes, in business only since 1869 after buying out their employer, Thomas B. Deffebach, found a novel way. They became "Printers to His Majesty, Norton I." The prerogative of any government is to issue money, and a fifty-cent imperial bond dated November 11, 1870, is the earliest scrip known. Cuddy & Hughes already printed African American Peter Anderson's Pacific Appeal and billheads, and six weeks later, His Majesty chose it as his official paper. The two ultimately produced five differently designed bonds for the Imperial Government of Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico. Today one of their fifty-cent notes brings $16,000.

Here's a Cuddy & Hughes imperial note that Emperor Norton signed and sold on 22 July 1875:

Bond of The Imperial Government of Norton I, made by Cuddy & Hughes and signed by Emperor Norton on 22 July 1875. Source: Heritage Auctions.

The line along the bottom edge — "CUDDY & HUGHES, Printers to His Majesty Norton I, 511 Sansome Street, S.F." — goes right to Chandler's point. Whatever might have been the personal sympathies of John Cuddy or Edward Hughes towards the Emperor, these notes were first and foremost — for them — advertisements for the firm. Within one small sheet, they were able to convey the quality of their paper; their design and typographical sensibilities / capabilities; and the quality of their printing.

CHARLES A. MURDOCK & CO. (1878–1880)

It's important to remember that the dates on Emperor Norton's notes are the dates when he signed and sold them — not the dates they were printed.

In a piece he penned for the Fall 2009 issue of the Brasher Bulletin, a publication of the Society of Private and Pioneer Numismatists, Robert Chandler included a table — researched and compiled by Donald Kagin — of the "Population & Provenance" of then-known imperial notes.

Kagin's table shows Cuddy & Hughes notes signed from November 1870 through August 1877.

That last date — August 1877 — is interesting. As it happens, Messrs. Cuddy and Hughes had dissolved their partnership in 1876. Cuddy initially moved to Oakland, where he worked for the Oakland Tribune. Hughes continued to run the "old firm" as the E.C. Hughes Co. — at 511 Sansome until 1906, when the building was destroyed in the earthquake and fires; then settling at 151 Minna, where his firm was listed the year of his death.

And, as we know, Peter Anderson at the Pacific Appeal had severed ties with the Emperor in May 1875.

Presumably, Emperor Norton simply had a stock of blank Cuddy & Hughes notes that lasted him deep into 1877.

What the Emperor did when he ran out — select a new printer — does beg questions.

Did E.C. Hughes Co. continue to print the Pacific Appeal — and, if so, was it simply too awkward for the Emperor to go back there for a new supply?

Had John Cuddy been the real soft touch at Cuddy & Hughes? Did the Emperor have a cooler relationship with Edward Hughes?

Whichever is the case, it appears that all the imperial notes signed from January 1878 until the Emperor's death in January 1880 — as well as what Kagin called an "unissued remainder" note from 1880 — were designed and printed by the firm of C.A. Murdock & Co., headed by Charles A. Murdock (1841-1928).

Emperor Norton liked the Unitarians — and one of the Emperor's favorite ministers was Horatio Stebbins, who succeeded Thomas Starr King at the First Unitarian Church.

Murdock — a staunch Unitarian — was a member of this church; and it seems that this is where he and the Emperor befriended one another.

Murdock's print shop was located at 532 Clay Street between Sansome and Montgomery Streets.

Listing for C.A. Murdock & Co. in Langley’s San Francisco Directory, 1878, p. 627. Collection of the San Francisco Public Library, Source: Internet Archive

Murdock’s notes are distinguished by the absence of any promotional copy for his own business — which may say any number of things about Murdock, probably all of them good.

Here's a Murdock note signed and sold by Emperor Norton on 20 November 1879.

Bond of The Imperial Government of Norton I, made by Charles A. Murdock & Co. and signed by Emperor Norton on 20 November 1879. Collection of the California Historical Society. Source: Groove Central LA

Charles Murdock was a keen and sensitive observer of his world. And he lived a deeply engaged and distinguished civic and professional life in San Francisco and Northern California — a life that provided him with a front-row seat to the early development of his adopted city and region, and that brought him in touch with many of its most notable writers and public figures, including Bret Harte, Mark Twain, John Muir and Joaquin Miller.

So it was that, in 1921, at the behest of friends, Murdock published a late-in-life memoir, which he modestly titled A Backward Glance at Eighty.

Here's Murdock's charming recollection of his relationship with the Emperor [emphasis mine]:

No glance at old San Francisco can be considered complete which does not at least recognize Emperor Norton, a picturesque figure of its life. A heavy, elderly man, probably Jewish, who paraded the streets in a dingy uniform with conspicuous epaulets, a plumed hat, and a knobby cane. Whether he was a pretender or imagined that he was an emperor no one knew or seemed to care. He was good-natured, and he was humored. Everybody bought his scrip in fifty cents denomination. I was his favored printer, and he assured me that when he came into his estate he would make me chancellor of the exchequer. He often attended the services of the Unitarian church, and expressed his feeling that there were too many churches and that when the empire was established he should request all to accept the Unitarian church. He once asked me if I could select from among the ladies of our church a suitable empress. I told him I thought I might, but that he must be ready to provide for her handsomely; that no man thought of keeping a bird until he had a cage, and that a queen must have a palace. He was satisfied, and I never was called upon.

And what Emperor could want a more empathetic printer than that?

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...