Edward Payson Hammond was a celebrity preacher — a Billy Graham of his day.

Today, Hammond is much less well-known in the annals of American religion than his crusading contemporary, Dwight Lyman Moody.

But, in the 1860s and 1870s, E.P. Hammond was a phenomenon.

In February 1875, Hammond brought his traveling revival road show to San Francisco for what turned out to be a two-month stand.

To get preaching gigs like this, Hammond claimed to produce hundreds — even thousands — of “conversions” everywhere he went.

To gin up these numbers, Hammond’s stock-in-trade was badgering tiny children into believing that they were evil sinners in danger of hellfire.

Emperor Norton was not down with this — and, he found a way to say so in a Proclamation that was published on both sides of San Francisco Bay in March 1875.

Read More

On 24 January 1880, a newspaper in Maine published evidence of an edict that Emperor Norton issued two weeks before his death on January 8th — but that was published the day of his funeral on January 10th — by a surprising source.

Read on for the story of our fascinating discovery — a discovery that raises many new questions!

Read More

For Empire Day 2020, The Emperor Norton Trust offers a free Zoom discussion of Emperor Norton's relationships with leading black intellectuals and editors of his day — as well as the Emperor's well-documented insistence on equality, civil rights and expanded legal protections for black people.

Read More

Emperor Norton’s on-point attendance at an early event of the Order of Freedom’s Defenders — a Unionist-Republican political club dedicated to preserving Lincoln's legacy; advancing Reconstruction; electing Grant as President; and securing the Constitutional protections necessary to guarantee the civil rights of African-Americans — can be seen as “of a piece” with the Emperor’s broader commitment to African-American equality.

Read More

In February 1869, the U.S. Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, which would have the effect of extending the right to vote in the United States to all men of color.

Ten months later — as ratification was making its way through the states, and with California still in the balance — a respected African-American editor and activist named Peter Anderson gave a lecture in favor of the Amendment at the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church, on Stockton Street in San Francisco.

Emperor Norton showed up, took a seat down front and was “an attentive listener,” according to the San Francisco Examiner.

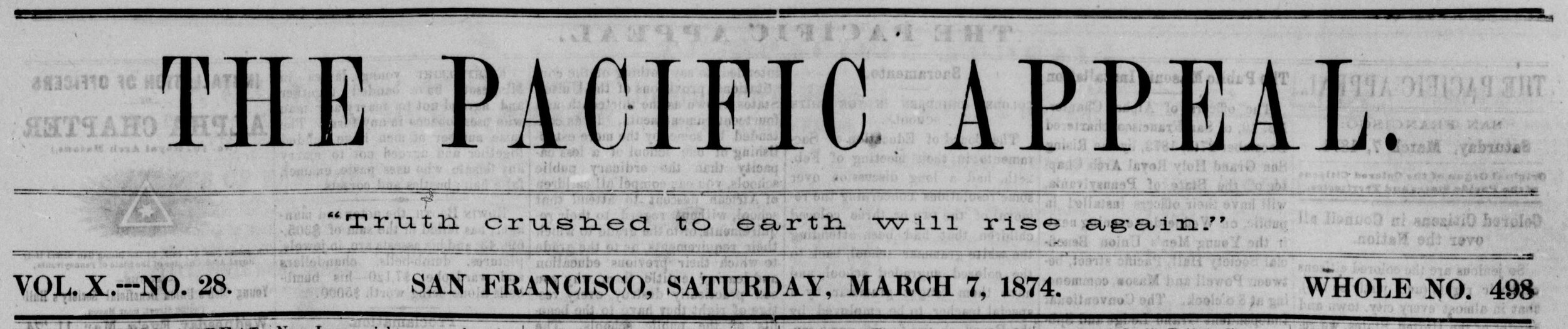

The Amendment was ratified in February 1870 — no thanks to California, where the legislature rejected the Amendment against a backdrop of anti-Chinese racism in the state. But, Anderson — the editor of the African-American-owned and -operated Pacific Appeal newspaper — may have remembered Emperor Norton’s solidarity when, late that year, he took on the Emperor as a regular contributor to his pages.

Over the next four-and-a-half years, Anderson would publish — almost always on the front page — some 250 of Emperor Norton’s proclamations, including those insisting on the rights of African-Americans to attend public schools and ride public streetcars.

Read More

In 1860, the prominent African-American editor and civil rights activist Philip Alexander Bell arrived in San Francisco from New York City to take up the editor’s chair at the San Francisco Mirror of the Times newspaper —the intellectual and political heartbeat of the emerging movement for African-American equality in California.

One of Bell’s earliest editorial items — published on 20 August of that year — was about Emperor Norton. Within a matter of hours, the Emperor responded in writing, and Bell published the note the following day under the headline “A Pacific Proclamation.”

Twenty months later, Bell would join Peter Anderson, a founder of the Mirror, in converting the paper to a new African-American weekly called The Pacific Appeal. At the end of 1870, Emperor Norton named the Appeal his imperial gazette; and, over the next four-and-a-half years, Anderson, as editor, published some 250 of the Emperor’s proclamations — including his many decrees recognizing the humanity and rights, and demanding fairness and equality, for marginalized and immigrant people, specifically: the Chinese, Native Americans and African-Americans,

The fact that Emperor Norton responded to Philip Bell in 1860 — and what he said — tells us much about the Emperor.

We believe this is the first modern publication of the images and full texts of Bell’s editorial and the Emperor’s reply.

Read More

It is known that Emperor Norton had his imperial promissory notes — his scrip — printed for him. But, rarely if ever discussed in any detail — even among collectors and connoisseurs of historical currency — are the particulars: Who were these printers? What were their associations? How did they get their "gigs" with the Emperor, and how did they fit into his world? Exactly when and where did they do their printing for him?

This exploration takes a close look at the two firms that are known to have printed Emperor Norton's bonds, between 1870 and 1880: Cuddy & Hughes and Charles A. Murdock & Co. It unearths:

- some of the earliest newspaper references to the Emperor's scrip — including by the Emperor himself;

- rarely seen photographic views of the building where Cuddy & Hughes, the Emperor's first printer, operated;

- a personal recollection of the Emperor that his second printer, Charles Murdock, published in 1921;

- directory listings; and...

Much other detail that sharpens the focus on this most basic episode of the Emperor's story — the printing and selling of scrip — and the key behind-the-scenes players that helped to make it happen.

Read More

"As everyone knows, the Emperor Norton I. visits this city every Monday." So wrote the Oakland Tribune newspaper on 30 December 1879, a little more than a week before the Emperor died on 8 January 1880.

Although Emperor Norton often is pigeonholed as a creature of San Francisco, the truth is that he spent quite a bit of time visiting places that were outside the seat of his Empire. Here's a look at two of those places — Oakland and the adjacent Brooklyn, Calif. — as well as two of the Emperor's proclamations that were datelined "Brooklyn."

Images include: the original Oakland Tribune item; archival 1850s-'70s maps of Oakland, Brooklyn and Alameda; and two "Brooklyn proclamations" of 1872. Bonus: The story of The Tom Collins Hoax of 1874.

Read More

It long has been known that, upon Emperor Norton's death in January 1880, many of his personal effects — including his regimentals, a hat, his sword and his treasured Serpent Scepter, an elaborate walking stick given him by his subjects in Oregon — went to the Society of California Pioneers (only to be lost 26 years later in the earthquake and fire).

Many, but not all. This week, we discovered archival traces of an early 1880 donation to the Odd Fellows' Library Association of San Francisco. The donation — by David Hutchinson, Emperor Norton's longtime landlord at the Eureka Lodgings — included the stamp the Emperor used to place his seal on his proclamations. It might also have included the Emperor's final proclamation: written and sealed, but not yet delivered and published.

Read More