Joshua Norton of Jackson Street

Evidence Doesn’t Support the Modern Claim That Norton’s San Francisco Business Empire Was Anchored on 3 Corners of Sansome & Jackson Streets

And: Did He Really Run A Rice Mill? Signals Are Mixed

ONE HAS TO double- and triple-check everything.

In his 1986 biography of Emperor Norton, William Drury wrote, of the pre-imperial Joshua:

On his made-ground at the southwest corner of Jackson and Sansome Streets, Norton opened a cigar factory. On the southeast corner he put up a large frame building, renting its rooms to businessmen. Then, on the northwest corner, he built a rice mill. It was crude — a mule provided the power, plodding endlessly around a ship’s wheel — but it was the first on the Pacific coast.

The idea here is that Joshua Norton, at the height of his prosperity and influence, held forth from a business hub that he heroically had assembled at three of the four corners of Sansome and Jackson Streets.

Although Drury provided no documentation for this claim, the claim has become part of the standard telling of the Emperor’s story — including by The Emperor Norton Trust.

But, it wasn’t part of earlier biographical accounts.

And, it wasn’t in the obituaries of 1880.

It begins to appear that the notion of a Norton business hub on three corners of Sansome and Jackson, with a rice mill on one of those corners, may have originated with the undocumented claim of William Drury in 1986.

:: :: ::

IT’S WORTH remembering that North Beach — including the intersection of Sansome and Jackson Streets — burned to the ground in May 1851. Here’s a detail from one of the “burnt district” maps that was produced at the time.

Detail from Map of the Burnt District of San Francisco, Showing the Extent of the Fire, c. 1851. California Lettersheet Collection, Kemble Spec Col 09, courtesy, California Historical Society, Kemble Spec Col 09_B143 . Source: California Historical Society

Plus: The beginning of the end for Joshua — the failed rice deal that sent everything south for him — was December 1852.

So, we’re looking at only about 18 months when Joshua Norton could have built or located in this area.

Absent other evidence for Joshua Norton’s business locations, there’s no other choice but to prioritize documented San Francisco directory listings and newspaper notices of the time — not least, because, as we’ll see, later recollections can be wrong. *

A.W. Morgan & Co.’s 1852 San Francisco directory, published in September 1852, listed Joshua Norton & Co. at 95 Jackson Street. This was on the south side of Jackson between Battery and Sansome. But, it was a couple of doors from the corner of Battery and Jackson — not on the Sansome end of the block.

Business listing for Joshua Norton in A.W. Morgan & Co’s San Francisco City Directory, 1852, p. 45. Source: San Francisco Public Library

James M. Parker’s 1852–53 San Francisco directory was published around the same time as Morgan’s — maybe a little later, but definitely still in 1852, as Parker’s introduction to the directory “urges upon our merchants and business men, the necessity of acquainting us with all…changes or removals, by letter or otherwise, in time for the issue of our first ‘extra,’ on the first of January, 1853.”

Parker includes a few listings for Joshua Norton, in addition to the 95 Jackson Street office:

Business and residential listings for Joshua Norton in James M. Parker’s San Francisco Directory, 1852, p. 81. Source: San Francisco Public Library

The Rassette House, the first-class hotel on the southwest corner of Sansome and Bush, is where Joshua Norton still was living in late 1852.

There are two listings for Norton at what apparently is the only documented business address for him at the intersection of Sansome and Jackson: 113 Jackson Street, at the southwest corner.

The fact that there are separate listings at this address for “Norton Josh, Segars” and “Norton & co. imp cigars” lends some credence to the possibility that Joshua Norton was both importing and producing cigars at this location.

A sidebar…

There is not sufficient evidence to say

whether Norton bought (or co-invested in) the land under 95 and 113 Jackson, either before or after the fire of May 1851;

whether he built and owned (or co-owned) one or more of these (or other) buildings in this area; or

whether he simply rented space built and owned by others.

This much we know: Immediately after the California Supreme Court issued its final October 1854 ruling against Joshua Norton in the “rice case,” numerous “Sheriff’s Sales” were held after various property co-investors sued Joshua Norton in connection with the court-mandated foreclosures on his interest in those properties.

What seems clear from this is that Joshua Norton was much more highly leveraged and financially exposed than what the conventional wisdom admits.

:: :: ::

EXCEPT FOR ONE reference that I’ll come to shortly, the only other mention of Joshua Norton in connection with the intersection of Sansome and Jackson would appear to be in the following excerpt from his San Francisco Chronicle “second obit” of 11 January 1880 (“Le Roi Est Mort”).

The Emperor’s old friend, Joseph G. Eastland, had taken the lead in securing funeral and burial arrangements and had started with R.E. Brewster, another old friend of the Emperor’s [emphasis mine]:

Mr. Eastland on the day following Norton's death took upon himself the task of securing for his old friend a funeral in some degree suited to his former circumstances. He went to R.E. Brewster and broached the subject. Mr. Brewster was also an old-time friend and associate of Norton, and like Mr. Eastland retained much respect for his character. He states that at one period of their early life here, Norton was engaged in the business of commission brokerage, and in one week did business for him amounting to many hundred thousand dollars. He added that at that time Norton was the best man in that line of business that he ever saw. His place of business was what is known as the Wright Building, on the northwest corner of Sansome and Jackson streets.

As one night expect from a 30-year-old memory, this one appears to have been a “false positive.”

What was known variously as “Wright’s Building” or “Wright’s Block” or “Wright’s Bank” was not on the northwest corner of Sansome and Jackson — it was on the northwest corner of Montgomery and Jackson.

It originally was built as the new headquarters of Dr. A.S. Wright’s Miner’s Exchange and Savings Bank.

And, it opened at the end of 1854 — when Joshua Norton was two years in to his spiral.

Joshua did have an office at the northeast corner of Montgomery and Jackson — in James Lick’s adobe at 242 Montgomery. But, that was in 1850. A different time.

:: :: ::

THE MOST intriguing address for Joshua Norton in 1852–53 might be 92 Jackson Street: Across the street from his office at 95. North side of the street. Immediately adjacent to, and to the west of, the northwest corner of Battery and Jackson at 90.

The extant San Francisco directories from this period don’t show any business listings for Joshua Norton at 92 Jackson. The connection appears in a series of newspaper ads that Norton began to run just a few days after the rice deal of 22 December 1852 was revealed to be a bust.

Here’s the first of these — a 3-day ad that ran in the Daily Alta starting on 28 December 1852:

Ad for Joshua Norton & Co., Daily Alta California, 28 December 1852, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Here’s a second one that ran in the Alta for 3 days starting on 16 January 1853:

Ad for Joshua Norton & Co., Daily Alta California, 16 January 1853, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

And, finally, this 6-day ad that ran in the Alta starting on 3 February 1853:

Ad for Joshua Norton & Co., Daily Alta California, 4 February 1853, p. 3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Less than two weeks after the end of this ad run, the following announcement appeared in the Daily Alta of 19 February 1853 for an auction to be held that day. It’s reasonable to guess that the location of the sale “[a]t the store of Joshua Norton, on Jackson st, near Battery” was 92 Jackson.

Ad for auction of Joshua Norton goods and equipment, by Rising, Caselli & Co., Daily Alta California, 19 February 1853, p.3. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

We’ll return to this announcement shortly.

But, from the timing and the enormous quantities of rice on offer, it seems clear that, between December 1852 and February 1853, Joshua Norton was trying, feverishly, to unload as much of his newly acquired “glut” of rice as he could — and that he was doing so from space secured for the purpose: 92 Jackson was a short-term emergency residency.

Indeed, Parker’s directory of 1852–53 confirms that 92 Jackson Street was “Hort’s building” — “Hort” being Samuel Hort, “com mer.”

Listing for “Hort’s building” in James M. Parker’s San Francisco Directory, 1852, p. 64. Source: San Francisco Public Library

What was the relationship between Joshua Norton and Samuel Hort?

Was Hort’s provision of space in his building a case of one commission merchant doing a fellow commission merchant a solid?

:: :: ::

BY THE TIME LeCount and Strong published their 1854 directory of San Francisco, the only listing for Joshua Norton was at 120 Montgomery, on the east side of Montgomery just south of Sacramento — well away from the stretch of Jackson between Battery and Sansome that had been Norton’s habitat for the previous couple of years.

Newspaper ads during this period tell us that Norton had not entirely given up on commodities brokerage — but, he is listed here as a “real estate dealer.”

Business listing for Joshua Norton, LeCount and Strong’s San Francisco City Directory, 1854, p. 102. Source: San Francisco Public Library

It appears that, by 1856, Joshua Norton no longer had a business address of his own. Colville’s San Francisco directory of 1856 has Norton with an “office” at Pioneer Hall. But, Pioneer Hall was the building of the Society of California Pioneers.

Did Joshua Norton really have an “office” here? Was it a place where he could receive visitors and take meetings, when and if a room was available? Or, was it just where he directed his mail?

Business listing for Joshua Norton in Colville’s San Francisco Directory, 1856, p. 162. Source: San Francisco Public Library

:: :: ::

CERTAINLY, Joshua Norton wasn’t milling rice by 1856.

One question to ask is: To what extent was Joshua Norton ever milling rice?

Take a closer look at that auction announcement from February 1853 (above). Among the things Norton is listed as selling: “2 Chinese hulling machines; 4 rice stampers complete; [and] 1 large iron winnowing machine.”

The fact that Joshua Norton had this equipment to sell suggests that at least he was planning to mill rice. But, did he? The newspapers of 1851–1853 don’t appear to carry any advertisements or notices that Norton was selling milled rice or even that he had added milling as a business capability.

In December 1862, the Marysville (Calif.) Daily Appeal reported [emphases mine]:

Editorial item in Marysville Daily Appeal, 19 December 1862, p. 1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

In the Fall of 1852 the first rice mill was erected in San Francisco, for Mr. Norton, (now called the “Emperor.”) The second mill was built in 1853 for Mr. Dunn and others.

The uses of the word “for” may be significant.

But, December 1862 was a full decade after the “beginning of the end” for Joshua Norton, businessman. Can this information be reliable?

Complicating matters further is the following excerpt from the obit that appeared in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin on 9 January 1880 [emphasis mine]:

In 1852 [Joshua Norton] purchased several cargoes of uncleaned rice, to arrive, with very high figures, with a view of controlling the rice market. Under a contract, George A. Dunn built FOR him the first rice-mill for cleaning rice ever erected on this coast. It occupied the lot of the northwest corner of Sansome and Jackson streets, and the primitive wooden morters and pestles were used. Through some misunderstanding with the consignees of the rice, he was refused delivery of the balance after a portion of it had been cleaned, and in consequence of the arrival in port of other cargoes of rice, prices declined and he became financially embarrassed. He then became a rice broker for Chinese house, and among them were the heaviest firms in the city. His office was located on the east side of Montgomery street, near Sacramento.

Again, we see a rice mill being built “for” Joshua Norton in 1852. But, here, the one doing the building — George A. Dunn — is the same one who, according to the Marysville Daily Appeal of December 1852, had his own rice mill built in 1853.

Here’s what appears to be the earliest ad for Dunn’s “San Francisco Steam Rice Mill” that the Daily Alta published in October 1853:

Notice for the San Francisco Steam Rice Mill, Daily Alta California, 9 October 1853, p.1. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Questions…

If George Dunn had the desire, and it was within his power, to open a steam-powered rice mill in October 1853, does it make sense to believe that he built Joshua Norton a mule-powered contraption with “wooden morters and pestles” a year earlier?

Were the Daily Appeal’s and the Bulletin’s 1862 and 1880 "accounts” of a Norton rice mill, published 10 and 28 years after events they purported to document, just foggy misrememberings?

Did Hubert Howe Bancroft have any more documentation to go on than these statements, when he included the following brief line in the volume of his History of California that he published in 1890?

Excerpt from Hubert Howe Bancroft, History of California, vol. 7 (1860–1890), 1890, p. 84. Source: Internet Archive

Did William Drury have any more than these three second-hand references to back up his own claim that, “on the northwest corner” of Sansome and Jackson Streets, Joshua Norton “built a rice mill” that “was the first on the Pacific Coast”?

Perhaps, there is original, contemporaneous documentation of this somewhere.

It’s hard to imagine that the Daily Alta would have failed to take note of such an achievement at the time.

But, there doesn’t to be any such editorial report in the Daily Alta of 1852. Nor does the Alta appear to have carried any advertisements or notices from Norton himself that he had added rice milling to his business capabilities.

Based on the available evidence, if Joshua Norton did have a rice milling operation of some description, it can’t have lasted for more than a few months — and not past a “soft launch”/test phase, the successful completion of which would have given Norton the confidence to “go public” with his new venture.

At best, one can speculate, Joshua Norton had just completed such a test, when the December 1852 rice deal put everything in disarray.

:: :: ::

BASED ON all this evidence and non-evidence, The Emperor Norton Trust has updated the pins and annotations of our Emperor Norton Map of the World.

View the relevant pins and click each pin for updated information here.

:: :: ::

A QUICK POSTSCRIPT…

In the years since William Drury published his biography of Emperor Norton in 1986, those who follow the Emperor have come to regard Drury’s book as something like a bible.

Virtually every account of the Emperor written, published or released over the last 35 years takes Drury as its starting point — often its ending point, too — and, indeed, doesn’t question or challenge any of Drury’s claims about the Emperor.

In what then was the first book-length account of Emperor Norton in nearly 50 years, William Drury did counter — and occasionally pushed back directly against — many of the baseless claims advanced by earlier Norton “biographers” of the 1920 and ‘30s: people like Robert Ernest Cowan, Albert Dressler, Allen Stanley Lane and David Warren Ryder. There’s no question but that Drury historicized Norton in a way that no one before him had done — and that, as a result, he advanced and elevated “Norton studies” far above where it had been.

But, not everything that William Drury wrote about Norton bears scrutiny. Sometimes, Drury incorporates earlier undocumented claims from the early-20th-century coterie into his own account — a notable example being his rubber-stamping of the wishful notion that Emperor Norton issued an anti-”Frisco” proclamation. And, at several points, Drury appears to reach into the cabinet of his own imagination for the thread he needs to stitch together a narrative that is not always fully supported by the documentary record. In these and other ways, Drury can be guilty of blurring the line between history and historical fiction.

From time to time, we have had to update our 2014 biographical essay on Emperor Norton to reflect new findings — latest revisions coming up! — but, from the beginning, the first sentence of the essay has read: “Emperor Norton is both a legend and an historical figure. It’s not always easy to tell where one begins and the other one ends.”

Especially given the countless inaccurate stories about Emperor Norton that have been told in the years since his public reign, those of us in the Norton Industrial Complex have to work to keep the history of the Emperor uppermost, even as we recognize the power of the myth.

But, we should be working at it. To give even a writer as respected as William Drury a “pass” on all his claims about Emperor Norton, or to keep on repeating 80- to 100-year-old tall tales about the Emperor without bothering to try to establish their veracity: this is to risk preserving and strengthening the toehold of a falsely mythical Norton, while making the truthfully historical — and often more wonderful — Norton that much harder to reach.

* Special thanks to Nick Wright of The History Alliance for assistance is sorting out the inscrutable mathematics of the street directories that appear in early San Francisco directories.

:: :: ::

UPDATE — 22 May 2022

On 22 December 1852, Joshua Norton and Co. contracted with the concern of Ruiz, Hermanos to buy a 200,000-lb. rice cargo on the ship Glide. Thirty days later, on 21 January 1853, the Ruiz brothers sued Joshua Norton & Co. for non-payment and breach of contract.

As we saw above, part of the fallout from this turn of events was an auction some four weeks later, on 19 February 1853, in which Joshua Norton sought to sell certain equipment and goods including “four rice stampers complete.”

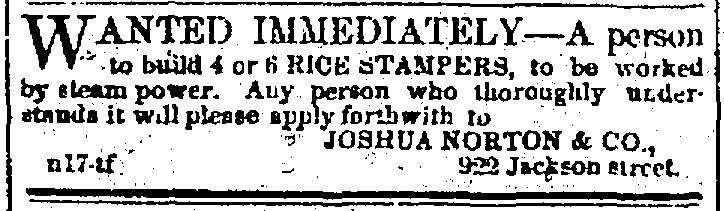

This makes intriguing our new discovery of a series of at least four ads that Joshua Norton & Co. ran in November and December 1852 wanting someone “immediately” to help build steam-powered rice stampers.

The address appears to be a misprint, as the address associated with Joshua Norton at this time was “92” Jackson Street.

The ads ran in the San Francisco Evening Journal; and one of them, possibly the last of the series, ran on 20 December 1852 — just two days before Joshua and his partners pulled the trigger on their 200,000-lb. rice buy.

It’s hard to know what to make of this. A rice stamper was a piece of equipment used to pound, i.e., stamp, hulled and cleaned rice grains into rice flour. So…

Were the “four rice stampers” that Joshua offered for sale in February 1853 more rudimentary human- or animal-powered stampers that he already had been using in some capacity?

Was Joshua’s slightly desperate-sounding ad of November and December 1852 a sign of his recognition that there was no way to fully capitalize on the rice monopoly he was planning without much better equipment than he had on hand?

At a minimum, the timing of these ads suggests that Joshua contracted for a shipload of rice without having in place the basic machinery to do anything with the rice but “flip” it, i.e., that he wasn’t in a position to turn the rice into a premium milled product (like flour) and sell that.

In late December 1852, Joshua Norton was way out over his skis.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...