Music Had Charms for the Emperor Norton

Scenes from the Early Days of Opera in San Francisco and Oakland

The Emperor enters this story late — but, as ever, he arrives right on time….

AN ITEM in the San Francisco Herald, reprinted in the Sacramento Daily Union of 20 October 1858, announced the arrival from Mexico of husband-and-wife Italian opera singers Eugenio Bianchi and “the Signora Casali.”

“Operatic Arrival,” Sacramento Daily Union, 20 October 1858, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

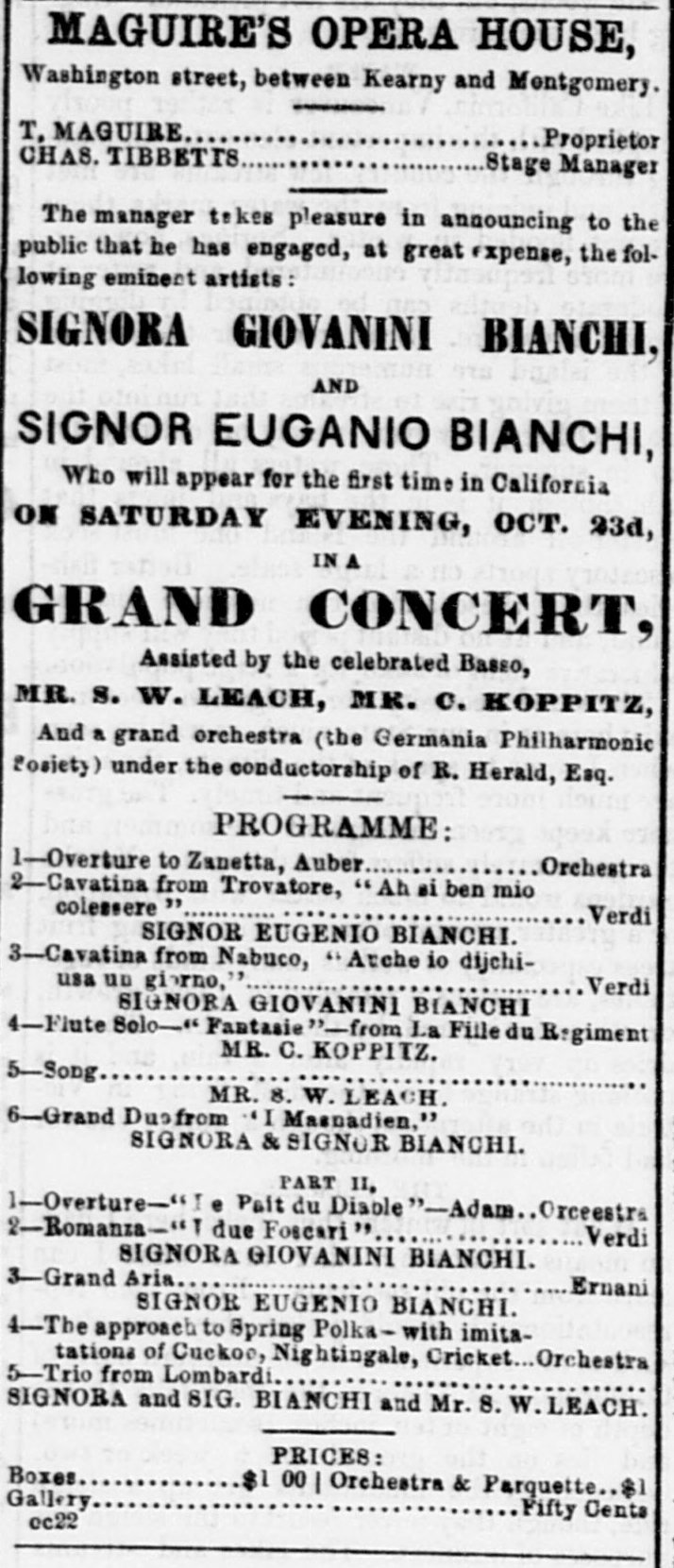

Two days later — in an ad that misspelled Eugenio as “Euganio” and Giovanna as “Giovanini” — Maguire’s Opera House announced the couple’s California debut the following night.

Maguire’s Opera House ad for California debut of Eugenio Bianchi and Giovanna Bianchi, Daily Alta California, 22 October 1858, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

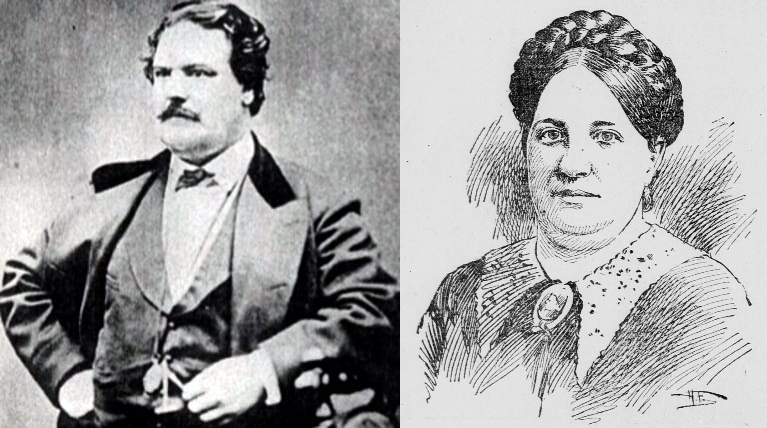

Here is an undated photograph of Eugenio Bianchi (1827–1895) and a drawing of Giovanna Bianchi (1828–1895) in her 30s.

Eugenio Bianchi (left), undated photograph in Graeme Skinner (University of Sydney), "A biographical register of Australian colonial musical personnel–B (Bi-Boz)", Australharmony (an online resource toward the early history of music in colonial Australia), entry on Eugenio and Giovanna Bianchi. Source: Australharmony; Giovanna Bianchi, drawing in obituary, San Francisco Morning Call, 23 February 1895, p. 4. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Remarking on the Bianchis’ inaugural concert of 23 October and a second Maguire’s Opera House performance on the 31st, the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin wrote, on 4 November:

It is expected that, before long, an operatic troupe will be formed here, or imported from the East, to support these artists, and give complete Italian operas.

Of course, the long-term success of any operatic troupe would depend upon on factors in addition to gifted musicians: a standing relationship with a suitable theatrical venue, for example, as well as a critical mass of ticket-buying opera lovers who could be relied upon to support the troupe’s performances year in and year out.

Ultimately, a “relationship” with a venue would trade on a relationship with the venue’s proprietor. Although Tom Maguire, the proprietor of his namesake opera house, was the first adopter in presenting Signor and Signora Bianchi and very recently had presented them again, an episode in June 1859 — in which Maguire sued the Bianchis for stealing opera scores belong to his house — threatened to derail any future collaboration:

Maguire and the Bianchis worked out their differences. But, as we’ll see, it was not the last time this theater owner and these opera singers would find themselves on opposing sides of a conflict.

A couple of months later, in August 1859, the Bulletin published a letter from an opera enthusiast with a prescient warning about the other externality that would be key to the success of any opera troupe: the cultivation of a loyal, paying audience.

At this moment, when opera was new and young in San Francisco, a theater’s mounting of specific opera performances depended almost entirely on subscriptions, i.e., advance season ticket sales. But, the writer observed, the subscription “seasons” were too short, risking the likelihood that patrons who subscribed once would not subscribe again in a matter of weeks — thus putting opera in general, the Bianchis in particular, at risk of failing for lack of money.

What was wanted, the writer said, was longer seasons subscribed at a level that would give theaters and musicians alike the confidence that they had the funding to produce and perform opera for several months, not just a few weeks.

:: :: ::

THE FOLLOWING YEAR, 1860, Eugenio and Giovanna Bianchi lit for Australia.

They intended to be away for a couple of months but wound staying for two years.

Whatever Australians might have thought about the Bianchis’ singing, this February 1861 item from The Age of Melbourne, Australia, indicates that some weren’t impressed with them as people:

Item on Eugenio and Giovanna Bianchi, The Age (Melbourne, Australia), 13 February 1861, p. 4. Source: Trove

Although, by 1859, San Francisco theater managers were contracting with additional singers to join the Bianchis in presenting concert programs of operatic arias and concert versions of operas, it wasn’t until after Eugenio and Giovanna Bianchi returned to San Francisco in mid 1862 that they assembled their own troupe of affiliated musicians capable of presenting fully staged and costumed operas complete with chorus and orchestra.

This additional capacity was helpful to the Bianchis when negotiating their engagements. But, even a decade later, in 1872, there were signs that funding and producing operatic performances that could reliably fill a given house remained a challenge.

A 13 April 1872 performance of Verdi’s Il Trovatore at Maguire’s Opera House featured both Bianchis (but apparently not their namesake troupe). The Daily Alta opened its review of the performance by noting the underwhelming size of the crowd:

Review of 13 April 1872 performance of Il Trovatore at Maguire's Opera House, Daily Alta California, 15 April 1872, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

The popular opera of "II Trovatore," with Miss Annie McKenzie as prima donna, was the attraction at this house on Saturday evening; but the audience was more fashionable than numerous, and though the musical and dramatic requirements of the occasion were satisfied in a manner that left little to be desired, and the applause was hearty and frequent, it would be contrary to the nature of things for the impresario not to feel somewhat discouraged at the numerically small patronage he is receiving.

:: :: ::

ONE PIVOT for theater owners and managers in San Francisco was to look for new audiences in Oakland. In February 1872, Tom Maguire’s brother, John Maguire, rented the Academy of Music in Oakland (on Sixth Street between Broadway and Washington), with a plan to present a mix of entertainment — including opera. (This Academy of Music is not to be confused to Tom Maguire’s second San Francisco theater, Maguire’s Academy of Music, on Pine Street between Montgomery and Sansome, in San Francisco.)

The debut opera outing at the Academy — a performance of Il Trovatore by the Bianchi troupe — was slated for 22 March 1872. Referencing the Metropolitan and California theaters in San Francisco, here’s how the Oakland Daily News previewed the performance on the morning of the 22nd:

We’ll wager something handsome against Emperor Norton’s old hat that the people of San Francisco who have heard that “Il Trovatore” is to be rendered here tonight, are ridiculing the idea that a paying house will witness the piece. Those who them have seen the interior of the Academy of Music have some reason for turning up their nasal organs, and yet there is no good reason why the Opera should not be received with eclat in Oakland. We shall not go to stare at the walls, nor criticize the upholstery of the seats, nor do we care about the limited size of the stage nor the lack of expensive and magnificent appointments connected therewith. We know that the Bianchi troupe can give us the piece billed for this evening in more than acceptable style, and if the same company could double itself and perform the same piece on the same evening at the Metropolitan or California, we should certainly save ourself a tedious trip across the bay and patronize the home production.

Alas, the performance did not take place. Explaining the last-minute cancellation, the Oakland Daily News wrote:

Yesterday, it was ascertained that the leading musicians of [Bianchi’s] orchestra had been employed to participate at the concert to be given by the Handel and Haydn Society, in San Francisco, last night. He was present last evening, and was greatly mortified at the disappointment. Rather than have the first Opera given with an imperfect orchestra, Mr. Maguire decided to abandon the present arrangement, and the hundreds who have bought tickets and paid for them will be refunded their money by Mr. Maguire, who will call upon the subscribers for that purpose.

According to John Maguire’s detailed account of the affair, published in the Oakland Daily Transcript on 10 April 1872, the truth of the matter was rather more complicated — with much of the complication down to the mercurial gamesmanship of Eugenio Bianchi.

The difficulty began early, when the vast majority of those who had promised to buy tickets for the performance reneged on their pledges — leaving Maguire holding the bag for the money he had personally fronted in order to move forward with the production. Maguire:

To carry out the idea [of opera], I canvassed Broadway at first, and the consequence was a splendid array of names from the enterprising tradesmen of “that ilk” for nearly two hundred tickets. Now, on the assurance that these would be “bona fide,” I immediately entered into negotions with Bianchi for the production of opera here….[A]fter having canvassed for names with success, I some five of six days after called round for the money in return for the number of tickets bespoke, but, “Ho Presto,” the whole thing had changed and not one-sixth of the tickets were taken, as in accordance with the promised subscription. Let it be borne in mind, that I at this time was at expense for the production of the opera, and besides the indirect losses to the business of the house.

Maguire had advanced Bianchi $100 of his total fee, to enable Bianchi to pay his musicians. Maguire contends that it was Bianchi who refused to perform when his preferred orchestral musicians failed to show and that, additionally, Bianchi insisted on immediate payment of the balance of his fee as a condition of singing — but that when he, Maguire, offered to go get him the money, Bianchi refused to wait for it and left.

Bianchi and one of his people came over here on the evening of advertised performance, stating that unless I had the opera without orchestra, I could have none that night. Now, how absurd was this proposition, can be best imagined by any lover of music, for in my mind, opera without orchestra is like Hamlet without the Prince. Still, rather than have any disappointment, I acquiesced and thought of having the opportunity of coming before the public that evening, and shifting the onus from myself to the proper parties. But Bianchi did not want to sing that evening, and immediately formed another excuse for postponement, which was money in hand on that instant. Now the Signor had had one hundred dollars in hand before this time for the purpose of, as he said, to advance to musicians. I had the balance ready, less one hundred dollars, which I told him would be given him in about twenty minutes. He would not wait an instant. I told him that there was no occasion to sing until he got every cent of the stipulated sum. To no purpose, Bianchi was inexorable, and in the spur of the moment he got into the cars for San Francisco, and that was the first and last of the Italian opera in Oakland.

With Maguire now under pressure to provide refunds to subscribers (with money he didn’t really have), Bianchi still refused to return the $100 advance, according to Maguire — even though the purpose of the advance now was moot.

Signor Bianchi held one hundred dollars of the money which I thought he certainly would not lay claim to, and I accordingly advertised that I would at a certain time refund subscribers. Bianchi would not give back the money.

After illustrating how he was “rushed on simultaneously by all parties to whom the theatre was indebted,” Maguire concludes by outlining his preparations to vindicate himself by finally presenting the promised opera at the Academy of Music:

In the face of so much loss, I was prepared to go on with the opera at all hazards, and would have gladly risked more to prevent the disappointment of that evening, and which, in its consequences have been nearly ruinous to me. Now, as I have stated the case plainly, I trust before the subscribers that they may comprehend the true situation of affairs. I having already incurred all the preparatory expenses, intend that Oakland shall have the opera. Bianchi is prepared to give credit for the one hundred dollars he retains.

In a parting shot, Maguire points out that

many of my theatrical troubles arose through the instigation of some of my supposed friends, who, I having laid the foundation, now wish to benefit themselves by opening an opposition theater. Hence the many insidious attempts against the present one.

But, Eugenio Bianchi’s return to the table does rather reinforce that impression that Bianchi was doing his own bit to game the situation to his maximum advantage.

Indeed, the single point of fact that John Maguire seems to repeat more than any other is that “Bianchi has his hundred dollars.”

Maguire wants it clearly understood that Bianchi’s reputation is on the line, too.

:: :: ::

IT WAS AGAINST this backdrop that Emperor Norton weighed in with the following Proclamation that was published in the Pacific Appeal newspaper on 20 April 1872 — a week-and-a-half after the publication of John Maguire’s letter in the Oakland Daily Transcript:

Proclamation of Emperor Norton, Pacific Appeal, 20 April 1872, p. 2. Source: California Digital Newspaper Collection

Proclamation.

Considering that the Opera tends to elevate and refine the public taste, and whereas Bianchi's Opera Bouffe are reported to be likely to cave in, for want of proper support. Now, therefore we Norton I, Dei Gratia, do hereby command all our friends and adherents to do all they can to prevent the Opera from being abandoned.

Norton I.

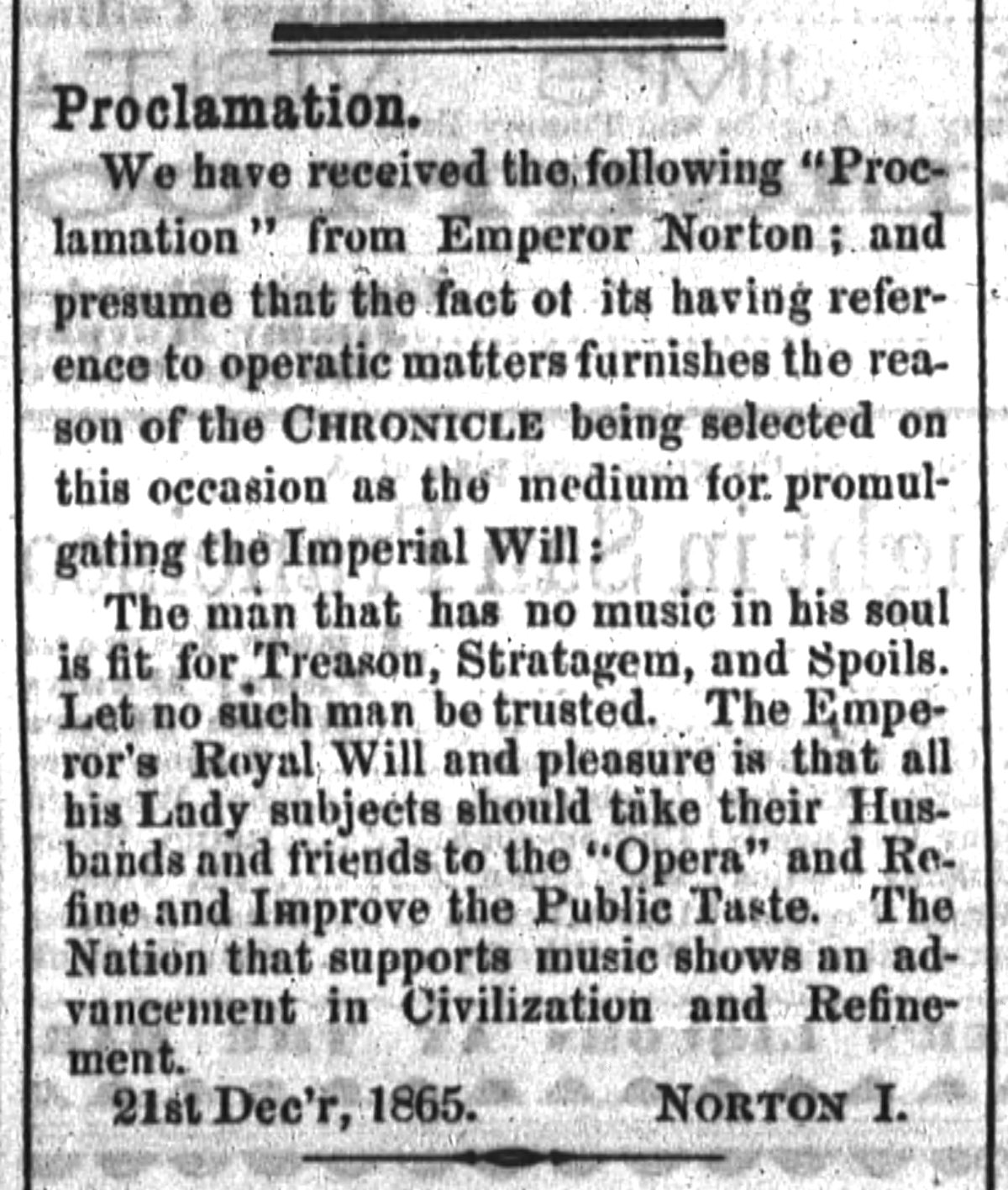

This is very similar, in spirit, to the following Proclamation published in the Daily Dramatic Chronicle (later renamed the San Francisco Chronicle) nearly seven years earlier, on 21 December 1865:

Proclamation.

The man that has no music in his soul is fit for Treason, Strategem, and Spoils. Let no such man be trusted. The Emperor’s Royal Will and pleasure is that all his Lady subjects should take their Husbands and friends to the “Opera” and Refine and Improve the Public Taste. The Nation that supports music shows an advancement in Civilization and Refinement.

Norton I.

Based on John Maguire’s account of the Academy of Music episode, one could read the Emperor, in his Proclamation of 1872, as laying most of the blame for the Bianchi troupe’s trials on fickle and faithless patrons. It seems clear enough that Maguire’s business plan for presenting the Bianchi troupe at the Academy depended on patrons’ buying X amount of advance tickets — and that, if they’d done so (as they pledged), Maguire would have had the liquidity to navigate those waters much more successfully.

In Maguire’s telling, though, the waters were choppy for a host of reasons — including Eugenio Bianchi’s bloody-mindedness.

An item in the Oakland Daily News of 6 May 1872 suggests that Bianchi’s being left in a lurch by his orchestra players for the Oakland performance six weeks earlier was not a one-time thing — and that there may have been deeper labor relations issues within the troupe:

There is trace evidence that the “Bianchi Opera Troupe” had the occasional traveling engagement, including in Los Angeles and Mexico, between 1873 and 1876. But a review of San Francisco newspapers from the period suggests that, indeed — although both Bianchis continued for some years to sing in operas produced by other companies and to be engaged as soloists — 1872 was the last year in which the Bianchi troupe was billed as presenting opera, or in which Eugenio Bianchi was credited as producing opera himself, in San Francisco.

So, perhaps the Emperor had intel beyond what was being reported in the papers when he issued his Proclamation in April of that year.

I’ve yet to turn up any documentation of Emperor Norton at a performance of the Bianchis — and will keep an eye out for that. But, given the Emperor’s strong advocacy for opera in his Proclamations of 1865 and 1872, it stands to reason that he was not writing “from a distance” but, rather, as one who had experienced the singing of Eugenio and Giovanna Bianchi firsthand.

:: :: ::

For an archive of all of the Trust’s blog posts and a complete listing of search tags, please click here.

Search our blog...