Did Two Emperors, Norton I and Pedro II, Really Meet in 1876?

The story goes that, when Pedro II, the Emperor of Brazil, visited San Francisco in April 1876, he and Norton I had a confab.

But, is this true?

Read MoreTO HONOR THE LIFE + ADVANCE THE LEGACY OF JOSHUA ABRAHAM NORTON

RESEARCH • EDUCATION • ADVOCACY

The story goes that, when Pedro II, the Emperor of Brazil, visited San Francisco in April 1876, he and Norton I had a confab.

But, is this true?

Read MoreIn recent years, there have been several claims on social media and elsewhere that Emperor Norton’s funeral in 1880 took place on the northeast corner of Bagley Place and O'Farrell Street, in San Francisco — on (or nearest to) the site of a building, still standing, that opened in 1910 as a bank; that in the last decade has housed an Emporio Armani store; and that today is home to the Museum of Ice Cream.

The temptation to connect this site to the Emperor’s funeral is understandable. The heavy, domed, stone-clad, temple-like edifice that now occupies the site has more than a touch of the funereal. Until very recently, the building had on the O’Farrell Street side medieval-looking, vault-like wooden doors that only added to the effect.

But, most likely, Emperor Norton’s funeral was across the street.

Read MoreThe informational web pages on Emperor Norton that were created and posted during the earliest days of the Internet are some of the most frequently shared resources on the Emperor. They also are some of the least historically reliable.

Here’s our shortlist of Norton pages that those who care about the Emperor’s legacy should “handle with care.”

Read MoreIn the 17 years since the San Francisco Chronicle noted in 2004 that the Emperor Norton Sundae no longer was on the menu at the Ghirardelli ice cream shop in San Francisco's Ghirardelli Square, the conventional wisdom has held that 2004 was when the “Emperor Norton” was removed.

But, I always have pointed out that 2004 is when the absence was noticed and reported as news — the removal itself could have happened earlier.

Turns out I was right. But, the cherry on top may be that the Emperor Norton Sundae has been hiding in plain sight at Ghirardelli — under a different name — for 20-plus years.

Read More

Eleanor Roosevelt cutting FDR’s birthday cake at the Willard Hotel, Washington, D.C., on 29 January 1938. Among the many notables who stayed at the Willard — or frequented its bar — in Emperor Norton's day were Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Julia Ward Howe, who wrote the lyrics to the "Battle Hymn of the Republic" while staying at the hotel. Photo: Library of Congress. For more on the Willard Hotel, click here.

The Emperor's Norton Trust’s seventh annual celebration of the Emperor's historical birthday on February 4th — a tradition we inaugurated with a party for the Emp's 197th, in 2015 — takes place on Thursday 4 February 2021 at 6 p.m. Pacific / 9 p.m. Eastern.

Read More

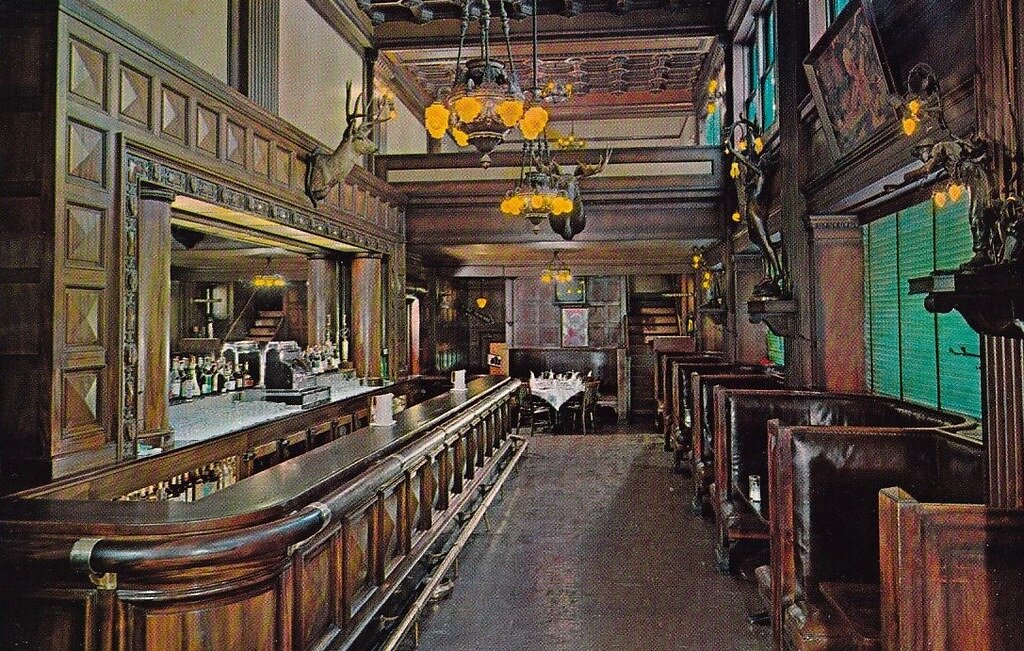

The House of Shields, in San Francisco, is the traditional site of the Tannenbaum Toast. This is the bar c.1950s. We hope to return in 2021. Photograph courtesy of Heather David.

The annual holiday party of The Emperor Norton Trust celebrates the legend that it was Emperor Norton who originally called for the raising of a great tree in Union Square every Yuletide season. (Another apocryphal tale, alas!)

The celebration traditionally takes place on the second Sunday of December in the mezzanine of the historic House of Shields bar, in San Francisco.

This year, we gather via Zoom. The Eighth Annual Tannenbaum Toast takes place on Sunday 13 December at 2 p.m. Pacific — and at all related times around the world.

The drink is the Boothby cocktail.

From late 1862 / early 1863 until his death in January 1880, Emperor Norton lived at the Eureka Lodgings — a kind of 19th-century SRO located at 624 Commercial Street, on the north side of Commercial between Montgomery and Kearny Streets, in San Francisco.

There is a handful of 1860s–1880s photographs, taken from across Montgomery or Kearny, that show distant views of the 600 block of Commercial Street.

What we’d never seen, though, is a photo of the 600 block of Commercial taken during the Emperor’s lifetime — taken from within the block — and showing the real, intimate flavor of the section of the street where Emperor Norton lived.

Our discovery, hidden in plain sight, is a c.1876 photograph apparently taken by Eadweard Muybridge.

A bonus: The photo appears to reveal a glimpse of the Eureka Lodgings itself.

If we’re right about this, we may have produced the first-ever visual ID of photographic evidence of the Emperor’s residence.

Kind of a big deal.

Read MoreIt appears that the earliest known photograph of Emperor Norton is a little earlier than we thought — and earlier than anyone else has said.

The case for the time frame that we focus on here draws on early artistic depictions of the Emperor and on one of the Emperor’s earliest sartorial choices, which is documented in an easy-to-miss newspaper item from May 1860.

Read MoreIn the Trivia Time feature that accompanied his 19 September 2020 history column for the San Francisco Chronicle, historian Gary Kamiya stated that Emperor Norton imposed a $25 fine for using the word “Frisco.”

In the Trivia Time that ran with his next column, published on 3 October 2020, Kamiya issued a correction and cited Emperor Norton Trust founder John Lumea as the authority for saying that “no primary documents have been found to support this claim.”

Read MoreThe conventional “wisdom” is that Joshua Norton arrived in San Francisco in 1849 with a $40,000 bequest from the estate of his father, John Norton, who had died in 1848.

But, if Norton arrived with $40,000, he almost certainly didn’t get it from his father — who had died insolvent and broke.

So, what was the source of Joshua Norton’s original funding — $40,000 or otherwise?

Andrew Smith Hallidie, the “father of the cable car,” knew Joshua Norton as Emperor — and probably before that as well.

In 1888, Hallidie published an article suggesting that Norton had arrived in San Francisco as a “representative and confidant” of English backers.

This is quite different from the account one often hears.

Read More

Detail from headline of article reporting on the 10 January 1880 funeral of Emperor Norton, San Francisco Chronicle, 11 January 1880, p. 8. Source: San Francisco Public Library.

When Emperor Norton died on 8 January 1880, there were 38 stars on the United States flag.

Remarkably, by the end of January, newspapers located in at least 33 of the current and future states of the Union had carried news of the Emperor’s death and funeral, as well as related stories and memories of the Emp.

Here is a listing of those papers that The Emperor Norton Trust has been able to determine took note of Emperor Norton’s passing during the month of January 1880.

We’ll add to the list as we learn of others.

Read More

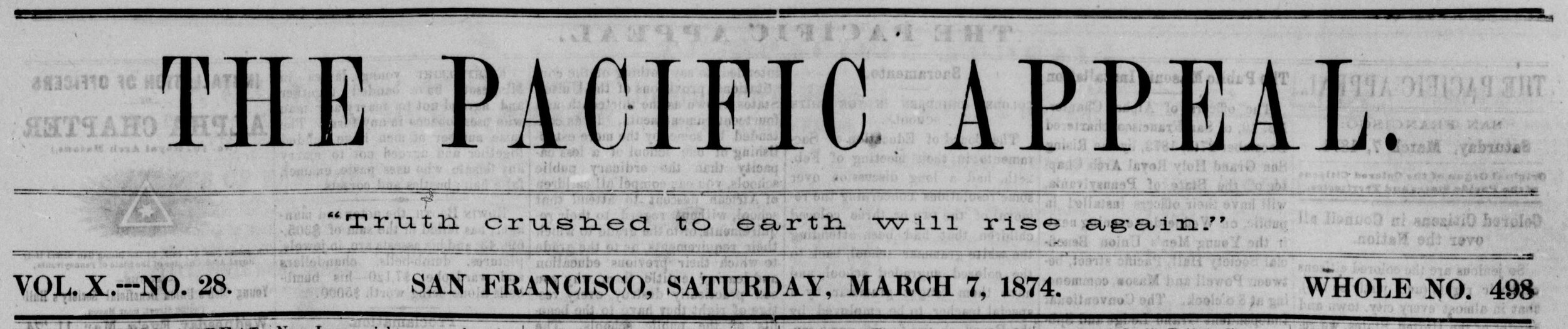

Banner of the black-owned and -operated Pacific Appeal newspaper, an abolitionist weekly in San Francisco. Between late 1870 and mid 1875, the Appeal published some 250 Proclamations of Emperor Norton. The issue of 7 March 1874, whose banner is shown here, featured a Proclamation in which the Emperor insisted that black children be admitted to public schools.

For Empire Day 2020, The Emperor Norton Trust offers a free Zoom discussion of Emperor Norton's relationships with leading black intellectuals and editors of his day — as well as the Emperor's well-documented insistence on equality, civil rights and expanded legal protections for black people.

Read MorePhotographs of Emperor Norton show that, just as the Emperor had a favorite walking stick, he also had a favorite hat pin — in the shape of a spread-winged bird.

Artists in the Emperor’s day painted and drew him wearing this pin.

It’s not surprising that contemporary San Francisco artists have rendered the bird as a phoenix.

Alas — spoiler alert! — it turns out that Emperor Norton did not wear a phoenix in his hat; the Emperor’s bird was a military American eagle.

But, this particular eagle does trace its heraldic roots to a phoenix — albeit it not a San Francisco one.

The fascinating story of how the phoenix of Scottish heraldry was transformed into the eagle of U.S. government iconography traces through the righteous Scottish cause of Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Continental Army coat buttons of George Washington and the design of the Great Seal of the United States.

One could say that Emperor Norton was wearing an eagle and a phoenix all at once: appropriate for an Emperor of the United States whose Seat was in the cool, grey city of love.

Pull up a chair!

Read MoreCharles Murdock was a friend of Emperor Norton.

He also was a fine printer who created and produced the Emperor’s promissory notes for two years — from January 1878 until the Emperor’s death in January 1880.

Here are four rarely seen photographs of Emperor Norton’s printer and good friend.

Read MoreLast week, a long-rumored and probably unpublished pair of stereocard photographs of Emperor Norton on a street in San Francisco’s Chinatown appeared on Facebook.

The Emperor Norton Trust is delighted to be able to publish, for the first time, large, hi-res images of the original stereocard, courtesy of the previous owner.

Read MoreA fondly regarded public artwork — a mural-sized rendering of Emperor Norton in bottle caps — came on the scene in The Mission, San Francisco, in late 2011.

It left quietly a few months ago.

Photographs and Google street views from 2009 to the present document the rise, fade and fall.

Read MoreAn extremely rare signed c.1864 Emperor Norton carte de visite is being auctioned right now via Bonhams.

Read MoreThe Emperor Norton mural in The Pied Piper, at the Palace Hotel, in San Francisco — painted by the city’s longtime “artist laureate,” Antonio Sotomayor (1904–1985) — is one of the best-known and -loved Emperor-themed works of art.

A newly discovered art-historical survey done for the San Francisco Arts Commission in 1953 offers an elusive date for the painting — and a new way of seeing it.

Includes rarely seen photographs.

Read MoreHere, we document our discovery of something we’ve never seen reported elsewhere: Emperor Norton’s attendance and participation at a “no party” political meeting held at the Mercantile Library, San Francisco, on 13 July 1875.

The Emperor’s role is included in next-day accounts from two San Francisco newspapers — the Daily Evening Bulletin and the Daily Alta California — as well as in a San Francisco dispatch that appeared in the Los Angeles Evening Express.

Read MoreThe period of the 1950s and ‘60s was a high-water mark of the Norton Cultural Complex in San Francisco.

Probably the best-known engine of “Emperor Norton awareness” during this time was the San Francisco Chronicle’s Emperor Norton Treasure Hunt. But, there were many other Norton-related projects, too — and some of them left behind beautiful physical traces.

At least three — perhaps all four — of the Nortonian artifacts discussed here trace their origins, production and promotion to the Chronicle.

And, two of them — a medallion and a medal — are relics of a “Grand Order of the West” that remains very mysterious indeed.

Includes rarely seen photographs.

Read More